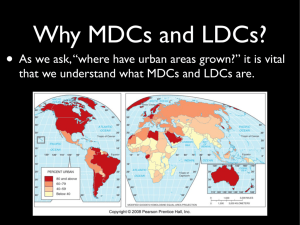

Duty and Quota Free Market Access for LDCs: United Nations

advertisement