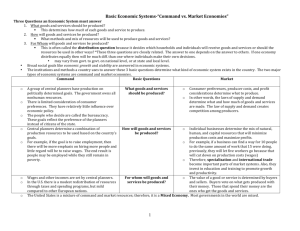

Executive summary

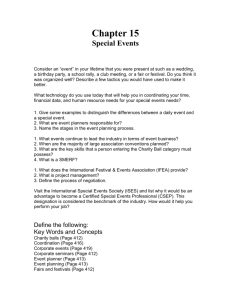

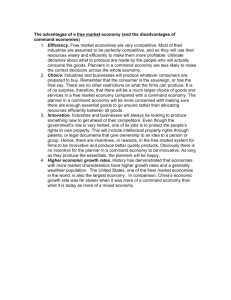

advertisement