Document 10436415

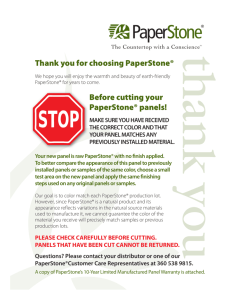

advertisement