Inter‐Agency Working Group SECTOR-SPECIFIC INVESTMENT STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN

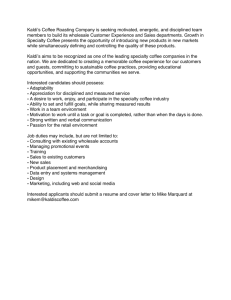

advertisement