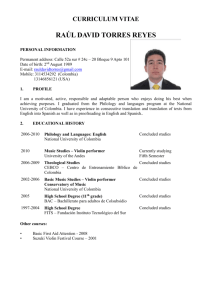

Document 10432032

advertisement