econ stor www.econstor.eu

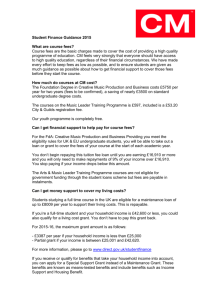

advertisement