Investment In PharmaceutIcal ProductIon In the least develoPed countrIes

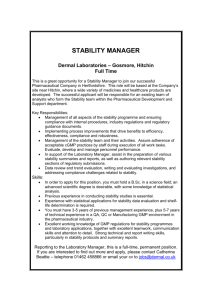

advertisement