Distribution and Ecology of the Fungal Dicranum fulvum Edna Bailey Sussman Foundation

advertisement

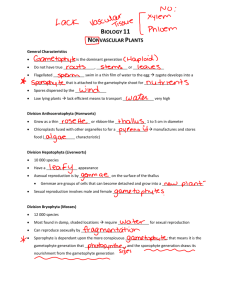

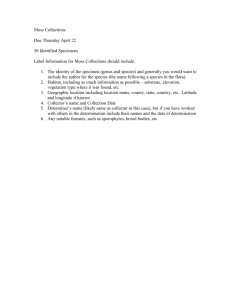

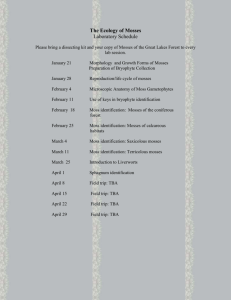

Distribution and Ecology of the Fungal Pathogen of Dicranum fulvum Edna Bailey Sussman Foundation Brittany Cronk December 2008 Summary of Proposed Work: Mosses, while small in stature, play a large role in forested ecosystems by providing habitat for other organisms and facilitating forest nutrient cycling. Mosses are generally thought to be disease resistant, but four years ago, an outbreak of an unknown pathogen began causing dieback in mosses at Cranberry Lake Biological station. The disease symptoms were observed in the moss Dicranum fulvum on the glacial erratics within the mixed hardwood forest. The boulders are a unique feature of the forest and support a diverse community of bryophytes, ferns, wildflowers as well as associated microbes and invertebrates. The symptoms include circular areas of dieback, a blackened plaster like appearance and a decrease in the overall height of the moss. The disease spread rapidly into other nearby boulder fields. It created large areas of moribund moss that was once a healthy green carpet. This moss is one of the most prevalent boulder top mosses in the hardwood forests of the Adirondacks. Destruction of this microhabitat could cause devastating effects on the ecology of microorganisms. The goal of my research is not only to identify the causal agent, but also to study the environmental variables involved and to learn about the spread of this devastating disease throughout the Adirondack park. My proposed work was to further investigate the growth rate of the disease, the interaction between the species as well as what environmental variables affect the spread in the field. This past summer I did studies on the disease of this moss throughout the Adirondack Park. The Wild Center, Natural History Museum of the Adirondacks had agreed to sponsor my project. My proposed work for this internship was to create a Cronk, «GreetingLine» 2 brochure that could be distributed to the public about the mosses that could be seen at the Wild Center. Narrative of Actual Work: I first began my fieldwork by creating a post card that I could leave at trail heads and gas stations that included a photograph, description of the moss disease and details on how the public could contact me if they happened upon the disease in their travels. Since I was just planning on searching for the moss, I figured this would be a good place to begin. Below is a photograph of the disease of Dicranum fulvum. Figure 1: Photograph of fungal disease of Dicranum fulvum. Photo taken at Cranberry Lake Biological Station , Sucker Brooke Trail, Summer 2007. I then traveled through the majority of the main roads throughout the Adirondack park, stopping at trail heads. My methods at each trailhead were as follows: - Hiked about 0.5-1 mile. - Looked for boulders that contained Dicranum fulvum. - Searched for disease within the moss carpets. - If I had found boulders that contained D. fulvum, I would create three quadrats along a line that was 50 meters. The quadrats had the radius of 1.78 meters. I would walk in a circle, which had the area of 10 m2 and measure all of the trees that fell within that area that were over 10 cm (4 in) diameter at breast height. This was performed at the 0 m, 25 m, and Cronk, «GreetingLine» 3 50 m marking along the 50 m line. This allowed me to get an idea of the forest’s tree composition. I had hypothesized that forest canopy not only affected the presence of D. fulvum growth on boulders, but that it could also affect the presence of the disease. - If there were symptoms or signs of disease I would sample all of the boulders along the 50 m line that fell within one meter of each side of the line. This gave a total sampling area of 100 m2. On each of the boulders I would perform point intersect transects on the boulders them selves. This involved using measuring tape to set up an X on the boulder and take notes one what moss was present at each 10 cm marking along the tape. This could give an idea what percentage of disease there was on the boulder as well as what other mosses and lichens were present. - At each site that I found D. fulvum (dead or healthy) I collected large samples of moss, originally planned for a nitrogen analysis. There have been studies that nitrogen can influence the virulence of a pathogen. Because mosses typically live in areas that are low in essential nutrients, an excess of nitrogen can stress the moss and make it more susceptible to infection. Also in the mixed hard wood forests for the summers of 2005 and 2006 there was a heavy Forest Tent Caterpillar outbreak that could have increased the amount of nitrogen (in the form of frass) on these boulders within these forests. I have not currently analyzed all of the data resulting from these studies but I had found disease of D. fulvum throughout the entire Adirondack Park. It seemed that had been spreading fast and the infections that I had observed were new. Boulders that were isolated in the forest, away from any nearby boulder field had also been infected. The disease did not seem to be impacted only in dense boulder fields close to nearby inoculum sites. I also recorded data on my existing sites that I had observed two years previously. This involved photographing existing disease rings on boulders to record growth rate changes. I am analyzing the photographs by using the program ImageJ. Images of a established control were also photographs. The controls were created in areas on the boulders that did not contain any disease symptoms. Throughout the three years many of the controls have developed symptoms of the disease. Observations were also collected Cronk, «GreetingLine» 4 for a transition matrix. This allows us to understand how the disease is affecting the ecology of the boulder tops. The transition matrix provides and idea on how the existing conditions will change from one year to the next. I am calling this fungal pathogen unknown because it is still in debate of what it is. I had originally thought that it was a cup shaped ascomycete within the genus of Bryoscyphus. I had isolated what I thought was this fungus in culture from the fruiting bodies found on the moss. I had done a small practice test where I inoculated moss to see if this fungus had produced any signs and symptoms against a control. This fungus had produce symptoms very quickly in the containers that had the highest concentration of inoculum. The control did not change. Then I isolated the DNA of this fungus and had it analyzed. I did a blast search within GenBank and it came back with 99% accuracy of being within the genus Fusarium. This all has to be repeated with a higher standard of accuracy before any results can be completely determined. For my internship I made a brochure on the mosses that can be found along the nature trail of the Wild Center. The public could use this brochure to learn more about different kinds of mosses and a bit about their ecology and roles in the ecosystem. The brochure can be found in a separate attachment. I also gave a powerpoint presentation on the ecology of mosses to a crowed of about 35 people. The lecture lasted about 1 hour, and then we regrouped and went on a moss walk where I distributed the brochure so that everyone could follow along. Within the group I had a mix of people with varying levels of background knowledge in ecology. Below are a few photographs of the moss walk. Cronk, «GreetingLine» 5 Figure 2: Observing the differences in characteristics of Polytrichum and Pleurozium. Director of Programs for the Wild Center, Jen Kretzer is in green. Figure 3: Describing how to observe the detail of the intricate architecture of moss using a hand lens. Discussion of Future Work: This internship allowed me to finish up all the field work necessary for my masters thesis research. In the near future I plan on analyzing the data using statitistcal anlaysis software. I plan on using the large collections of moss to re-isolate the fungal pathogen as well as using moss spores to grow D. fulvum in sterile culture. Then I can reinoculate the moss and with a more accurate and precise method, I could really prove pathogenicity. I will also perform another round of DNA analysis and identify the fungus. Cronk, «GreetingLine» 6 Identification, proof of pathogenicity and an understanding of the ecology of the disease would all be included in my masters thesis. Any published works that come from this research will acknowledge the Edna Bailey Sussman Foundation for their outstanding contribution to my research. Thank you for giving me this opportunity. Cronk, «GreetingLine» 7