Document 10420828

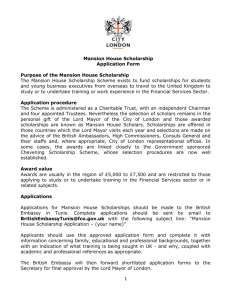

advertisement