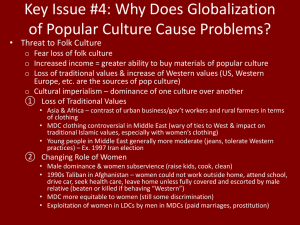

T L D C

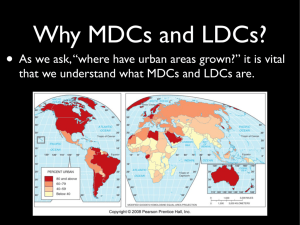

advertisement