THE LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES REPORT 2009 OVERVIEW The State and Development Governance

advertisement

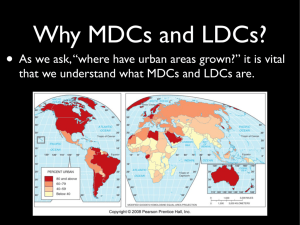

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT THE LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES REPORT 2009 The State and Development Governance OVERVIEW by the Secretary-General of UNCTAD UNITED NATIONS EMBARGO this Report The contents of oted must not be qu t, broadcast in pr e th in d summarize before ia ed m c ni or electro ho :00 urs GMT 16 July 2009, 17 UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Geneva The Least Developed Countries Report 2009 The State and Development Governance Overview by the Secretary-General of UNCTAD UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All references to dollars ($) are to United States dollars. A “billion” means one thousand million. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but a­ cknowledgement is requested, together with a reference to the document number. A copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint should be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat. The Overview contained herein is also issued as part of The Least Developed Countries Report 2009 (UNCTAD/LDC/2009), sales no. E.09.II.D.9). UNCTAD/LDC/2009 (Overview) This Overview can also be found on the Internet, in all six official languages of the United Nations at www.unctad.org/ldcr 1. Implications of the global economic crisis in LDCs: A turning point for change The Least Developed Countries Report 2009 argues that the impact of the global economic crisis is likely to be so severe in the least developed countries (LDCs) that “business as usual” is no longer possible. This will necessitate a rethinking of the development paradigm. The magnitude of the crisis offers both the necessity and an opportunity for change. Coping with the impact of the crisis in LDCs will require an innovative and informed policy design response. But beyond this, new policy approaches are necessary to ensure that development after the crisis will be more resilient and more inclusive. It is widely recognized that the current financial crisis is the result of weaknesses in the neo-liberal model that has been shaping global economic policies in the last three decades, weaknesses that have been magnified by policy failures and lax regulation in the advanced countries. The cost in terms of the bailouts and recapitalization of banks has already reached unprecedented levels. However, the adverse impact on the real economy and the cost in terms of lost output and employment are now the great concern. Most advanced economies are in recession and emerging markets are undergoing significant slowdowns. But the LDCs are likely to be particularly hard hit in the coming period. Because they are deeply integrated into the global economy, they are highly exposed to external shocks. Moreover, many are still suffering the adverse impact of recent energy and food crises, and they have the least capacity to cope with yet another major economic disruption. The combination of high exposure to shocks as well as weak resilience to those shocks is likely to mean that the LDCs, which already face chronic development challenges, will be harder hit than most other developing countries. The crisis is already undermining those factors that enabled the strong growth performance of the LDCs as a group between 2002 and 2007. Their vulnerability is not just a reflection of traditional commodity dependence and related sensitivity to price fluctuations; it is due to the combined threat from falling commodity prices, the slowdown in global demand and the contraction in financial flows. As a result, manufactures and service exporters (mostly Asian and island LDCs) are likely to be hit hard, but the commodity-dependent economies (mostly African LDCs) will be hit even harder. The LDCs are unlikely 1 to weather the crisis without considerable additional international assistance in the short run and support for alternative development strategies in the longer run. Changes on both fronts will be needed to induce a steadier and more resilient development trajectory. As noted in previous Least Developed Countries Reports, most LDCs (with the exception of oil-exporting LDCs) have quasi-chronic deficits in their trade and current accounts. Faced with decreasing global demand — UN estimates in May this year expect world gross domestic product (GDP) to decline by 2.6 per cent in 2009 — the current account imbalances are likely to deteriorate even further as export revenue diminishes. The vulnerability of LDCs is related to the highly concentrated production and export structures of commodity-dependent LDCs, especially African LDCs, as well as the dependence of Asian LDCs on low-skill manufactures. The global recession is likely to constrain international Selected commodity price indexes, Jan. 2000-Feb. 2009 Index 2000=100 (Index, 2000=100) 800 500 700 400 600 300 500 200 400 100 300 0 200 -100 100 -200 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 All food (right scale) Crude petroleum (left scale) Agricultural raw materials (right scale) Minerals, ores and metals (left scale) Source: UNCTAD secretariat calculations based on data from GlobStat. 2 -300 2009 trade and impede long-term investment, representing an additional source of contraction of LDC output and exports. Asian LDCs are somewhat more diversified and can better withstand the crisis, although their situation is hardly enviable. The crisis is likely to result in substantial reduction of their exports (both in volumes and prices) associated with a slowdown in global demand, especially in China and India. The external payments imbalances on the current account are likely to be exacerbated by trends in capital flows. Private capital flows, including both FDI and remittances, are predicted to decline, and if the experience of previous economic crises is repeated, official development assistance (ODA) will decline, too. In this context, the future of ODA will be vital. The international reserves of LDCs accumulated during the years of export boom may be insufficient protection from significant and persistent current account shocks associated with the drying up of external sources of finance. Excessive commodity dependence exposes most LDCs to large terms of trade shocks. Indeed, many countries have recently gone through years of record growth performance driven primarily by commodity sectors and propelled by the boom in international prices stemming from speculation in commodity derivatives. In mid-2008, however, the eruption of the global crisis put a sudden end to this boom and there have since been sharp price reversals. Such boomand-bust cycles have contributed to output volatility and uncertainty, thereby discouraging investment in long-term development of productive capacities. A sharp contraction in commodity markets is particularly damaging to LDCs for an additional reason; contractions in demand, prices and output imply a reduction in government revenues, thereby reducing the capacity of the state to utilize fiscal policy to mitigate output volatility. Moreover, external vulnerability of LDCs is further aggravated by their high level of indebtedness; in LDCs, the debt burden represents on average 42 per cent of gross national income, compared to 26 per cent in other developing countries before the crisis. As UNCTAD has repeatedly warned in recent months, there is the potential for a new debt crisis to emerge in poor countries. For many LDCs, the current crisis can jeopardize their hard-won debt sustainability. What happens in the future to external financial flows is critical. Although there may be differences from country to country, the general expectation is that foreign direct investment (FDI) to LDCs will decline over the next few years, owing to (a) lower expectation of profitability; (b) reduced access to credit to 3 finance new investments; and (c) balance sheet consolidation by transnational corporations in the face of financial pressures. This is particularly true of FDI to LDCs, which has been predominantly natural resource-seeking and focused on the extractive sectors, and which is likely to decline during 2008 and beyond because of sharply falling mineral prices and the transnational corporations’ cautious approach to exploration and expansion during this volatile period. Remittances are also set to decline. Workers’ remittances have become an important supplement to basic incomes in LDCs, where they generally support consumption rather than investment. According to World Bank estimates, remittances to developing countries as a whole have been increasing at a slower pace in recent years, with the annual increase down from 18 per cent in 2006 to 9 per cent in 2008. They are expected to decline by 5 per cent in 2009, with a possible slight recovery in 2010. Against this background, official aid trends will become a central determinant of what happens to LDCs. Unfortunately, past experience shows that ODA tends to decline during recessions in donor countries. It will be critical that donors maintain the levels of aid to the LDCs and also honour their commitments for increased aid. As we have argued in past Least Developed Countries Reports, there is a major tension between aid delivery mechanisms, including the working of policy conditionality, and national ownership of policies. It is therefore vital that the increased aid dependence – which is a likely outcome of the crisis – is not associated with diminished policy space, in the sense of the ability to choose appropriate policy options. The recent financial and economic crisis has exposed the myth of selfregulating markets. In response to the crisis, most large developed market economies have shifted away from free market-based forms of economic governance and are exploring alternatives that include a much bigger role for the state in economic management. These countries recognize that the alternative has to involve giving the state a greater role, not only through regulation but — more importantly — through Keynesian fiscal stimulus packages, of the kind being currently pursued in most large Western nations. Yet, this tendency has been more evident in the advanced countries than in the developing world. More recently, several larger developing countries — such as China, Brazil and South Africa — have begun to deploy public stimulus packages to revive their economies. However, most LDCs simply cannot afford to deploy similar packages. 4 In the last decades, most LDCs have followed economic reform programmes which have severely reduced government involvement in promoting development. However, these programmes have not been able to address the key structural constraints which LDCs face, including (a) bottlenecks in production, related to the structure of their balance-of-payment deficits; (b) inadequate infrastructure; (c) chronic deficits; (d) serious skills and knowledge shortages; and (e) vulnerability to external shocks. Furthermore, these policies based on minimal government action have not led to structural change and economic diversification. Instead, LDCs have even further deepened their unfavourable production patterns and specialization in exports of commodities, and many LDCs have undergone deindustrialization and seen stagnating performance of their manufacturing sectors. This has increased their exposure and vulnerability to external market shocks. The current financial crisis thus exposes a deeper, long-term development problem. Despite record rates of GDP growth over the last five years, coinciding with the commodity boom, poverty reduction has been slow in the majority of LDCs, and most remain off-track to meet the Millennium Development Goals. In addition, many are facing recurrent crises of food security. These patterns are rooted in the combination of an accumulating crisis in agriculture as well as an inability to generate productive employment outside agriculture. The crisis in agriculture is rooted in structural problems of declining farm size, low productivity, inadequate infrastructure and environmental degradation. The result is that it has been difficult for the sector to play a dynamic role in the developmental process through providing an expanding national market and source of inputs for domestic producers. But at the same time, it is proving impossible to generate productive employment outside agriculture, in particular in manufacturing. The current economic crisis creates both the necessity and the opportunity for a change of direction. This Least Developed Countries Report is based on the view that the crisis should be grasped as a turning point in the development path of LDCs. In order to overcome LDCs’ structural constraints and reduce their external dependence, it is necessary to reconsider the role of the state. The market only works through incremental changes and small steps. However, LDCs need to stimulate investments by socializing risk, in order to achieve long-term structural 5 transformation. The market has not been and will not be able to carry out these changes alone. The critical question now is not simply how LDCs can cope with the shortterm immediate impact of the crisis. More important, the question is how can they emerge from the crisis in a stronger position? What policies should they be crafting now for the post-crisis era? The present Report suggests that three major policy orientations are required: • Firstly, there is even more reason now to refocus policy attention on developing productive capacities. This means that policies should be oriented towards stimulating productive investment, building technological capabilities, and strengthening linkages within and across sectors and between different enterprises. Strengthening domestic productive capacities should also be aimed at producing a wider range of more sophisticated products; • Secondly, it is necessary to build a new developmental state. This is not a matter of going back to old-style development planning, but rather a question of finding new forms of development governance appropriate for the twenty-first century. Such development governance would be founded on a strategic collaboration between the state and the private sector, that will encourage the structural transformation of LDCs from agrarian to postagrarian economies; and • Thirdly, it is necessary to ensure effective multilateral support to LDCs. This is not simply a question of more and better aid, but also the design of rules that govern international economic relationships with regard to trade, finance, investment and technology flows, in ways which would support development in LDCs. It is also critical that support for LDCs does not impose unnecessary limits to the measures that governments can take to promote development, structural transformation and poverty reduction. Both national and international policies are necessary. However, this Report leaves aside the question of effective multilateral support and focuses on the second orientation mentioned above, namely the national policies and institutions for promoting development and the possibility of building the developmental state in a way which is adapted to the challenges and concerns of LDCs in the twentieth-first century. This will allow addressing the first policy orientation mentioned above. 6 2. The role of the State in promoting development in LDCs The basic argument of this Report is that, in the wake of the financial crisis, there is a need to rethink the role of the state in promoting development in LDCs. However, neither the good governance institutional reforms which many LDCs are currently implementing, nor the old developmental state, including successful East Asian cases, are entirely appropriate models now. Addressing the structural problems of LDCs will require a rebalancing of the roles of the state and the market. Discussion on the issue of governance must move beyond unhelpful and false dichotomies. Governments do not face a stark choice of good versus evil, the “vice” of state dirigisme versus the “virtue” of markets, privatization and deregulation. This is a false caricature. The institutions of the “state” and the “market” have always coexisted organically in all marketbased economies; hence, the “choice” between the market and the state is a false dichotomy. This has been recognized at least since the time of Adam Smith, although these insights have been lost in subsequent interpretations. The challenge is to design effective governance practices which interrelate states and markets in creative new ways in the service of national development within a global context. What is required now is a developmental state that is adapted to the challenges facing an interdependent world in the twenty-first century. This state should seek to harness local, bottom-up problem-solving energies through stakeholder involvement and citizen participation that creates and renews the micro-foundations of democratic practice. It should also embrace a wide range of development governance modalities and mechanisms within a mixed economy model to harness private enterprise, through public action, to achieve a national development vision. The limits of the good governance institutional reforms What constitutes “good governance” is inevitably contestable because the goodness of governance rests on values and ethical judgement. One list of the core principles of good governance which has been suggested and is useful, because it is universal rather than culturally specific, is the following: 7 • Participation: the degree of involvement by affected stakeholders; • Fairness: the degree to which rules apply equally to everyone in society; • Decency: the degree to which the formation and stewardship of the rule is undertaken without humiliating or harming people; • Accountability: the extent to which political actors are responsible for what they say and do; • Transparency: the degree of clarity and openness with which decisions are made; and • Efficiency: the extent to which limited human and financial resources are applied without unnecessary waste, delay or corruption. These principles, together with a commitment to predictability in policies and rules, could be realized through a variety of institutions or institutional configurations. It must also be recognized that the goodness of governance is not simply a matter of processes of governing, but also a question of effectively achieving outcomes. It would be a curious type of “good governance” if the governance processes were considered to be perfect, according to the valued principles, but the outcomes were poor. For a country concerned with promoting development, good governance should thus also encompass governance which effectively delivers development. LDCs should aspire to a kind of good governance in which the practices of governing are imbued with the principles of participation, fairness, decency, accountability, transparency and efficiency in a non-culturally-specific way. They should also aspire to a kind of good governance which delivers developmental outcomes, such as growing income per capita, achieving structural transformation, expanding employment opportunities in line with the increasing labour force and reducing poverty. However, at present, the good governance institutional reforms which are being propagated and undertaken in the LDCs are founded on a much narrower view of what constitutes good governance. This narrower view does not have an explicit developmental dimension. The narrower understanding is rooted in an implicit dichotomy between good and bad government systems. This contrasts a formalized type of good governance system with an informal, personalized, bad governance system. Both 8 these governance systems are “ideal types”, i.e. abstractions from individual countries, with the good governance systems stereotypically understood to be typical of developed countries, whilst the bad governance systems are stereotypically understood to be typical of poor countries. The good governance institutional reform agenda seeks to turn these bad governance systems into good governance systems. This involves introducing into developing countries particular types of institutions which are characteristic in developed countries. It has also involved prescribing a particular role for the state. One major type of institution which the good governance reform agenda seeks to introduce is electoral democracy. This intrinsically valuable institution is intended to ensure that policies and governance practices are regularly scrutinized by the general public. The good governance agenda also includes a style of public administration and management known as “new public management”. This approach advocates that government should be run according to private sector styles of management with an active, visible handson approach, using market mechanisms, client orientation and performance management to increase productivity, often favouring the unbundling of monolithic organizations into corporatized units and decentralization. The role of the state that the current good governance reform agenda prescribes is essentially to support markets by adopting policies and providing institutions that free markets to work efficiently. Initially, in the 1980s, the institutional reforms were oriented towards a minimal and laissez-faire state. But since the 1990s, there has been limited recognition of the existence of market failures as well as the need to build states which can capably support markets. From this perspective, particular priorities for institutional reforms have included (a) achieving and maintaining stable property rights; (b) maintaining good rule of law and contract enforcement; (c) minimizing expropriation risks; (d) minimizing rent-seeking and corruption; and (e) achieving transparent and accountable provision of public goods, particularly in health and education, in line with democratically expressed preferences. Irrespective of the intrinsic value of the institutions recommended in this reform agenda, an important question for LDCs seeking to promote economic development is whether or not these institutional reforms deliver instrumentally for development. 9 This issue unleashes fierce passions. The evidence is clouded by severe methodological problems in measuring the quality of institutions. One critical insight from cross-country statistical analyses is that the quality of governance is closely associated with levels of per capita income. That is to say, according to the indicators, high income per capita is associated with good governance practices and low income per capita with the absence of good governance practices. However, it is much more difficult to identify a close relationship between the quality of governance and growth of per capita income over time. As the United Nations Committee for Development Policy, which reviews the list of LDCs, put it in its annual report in 2004, “There is some empirical evidence to suggest that weak governance reinforces poverty”, but the relationship between governance and poverty reduction is not yet decisively proven and “in the absence of conclusive evidence, it is plausible to suggest that the link sometimes exists, but that at other time, there is no link”. This is particularly “in the light of the superior economic performance for some countries that are not ranked very highly with respect to good governance”. Existing practice of implementing the good governance reform agenda on the ground also shows that the agenda is so ambitious that it can lead to reform overload, which is itself incapacitating. In the end, it is questionable whether it is possible or desirable to transfer institutions of governance which are functioning in advanced countries into very poor countries with a much smaller financial resource base. The average government final consumption expenditure (an amount which covers all government current expenditures for purchases of goods and services, including compensation of employees) in LDCs in 2006 was just $60 per capita. This may be compared with $295 per capita in lower-middle-income countries, $1,051 in upper-middle-income countries and $6,561 in high-income countries. The central question is, “How can the institutions of rich countries be expected to work with this financial base?” The answer is that they cannot. A forward-looking agenda for development governance LDCs need to go beyond the current good governance institutional reform agenda and pursue good development governance. Development governance, or governance for development, is about creating a better future for members of a society through using the authority of the state to promote 10 economic development, and in particular to catalyse structural transformation. In general terms, governance is about the processes of interaction between the government — the formal institutions of the state, including the executive, legislature, bureaucracy, judiciary and police — and society. Development governance is governance oriented to solve common national development problems, create new national development opportunities and achieve common national development goals. This is not simply a matter of designing appropriate institutions, but also a question of policies and the processes through which they are formulated and implemented. Which institutions matter is inseparable from which policies are adopted. Development governance is thus about the processes, policies and institutions associated with purposefully promoting national development and ensuring a socially legitimate and inclusive distribution of its costs and benefits. During the 1960s and 1970s, development planning was very common. Indeed, LDCs were often recommended by international financial institutions and donors to engage in development planning. After the debt crisis of the early 1980s, structural adjustment programmes were generally adopted in most LDCs and they discontinued development planning and policies designed to promote development and dismantled their associated institutions. The role of the state in economic life was drastically downsized, as there was a shift towards laissez-faire embodied in a reform programme of stabilization, privatization, liberalization and deregulation. However, some developing countries, notably in East Asia, maintained and evolved the apparatus of a developmental state throughout this period. In calling for development governance now, this Report is not arguing for a return to old-style development planning. Nor is it calling for a return to the developmental state of the 1960s and 1970s. It must be recognized that there have been both successes and failures associated with developmental state action. However, the Report does argue that it is possible to design a forwardlooking agenda for development governance in LDCs by drawing lessons about economic governance in successful developmental states in the past and by adapting them to the twenty-first century. The main lessons from economic governance from successful developmental states are that national policies were oriented to promoting structural transformation and this was achieved through a mix of macroeconomic and sector-specific productive development policies. These sectoral policies were 11 directed to both agriculture and the non-agricultural sectors. Agricultural policies were designed to address the structural constraints limiting agricultural productivity and build up domestic demand in rural areas in the early stages of development. But they were complemented by an industrial policy which fostered structural transformation both intersectorally and intrasectorally. This policy mix was not simply about establishing new activities, but rather aimed at promoting capital accumulation and technological progress as the basis for dynamic structural change. In the language which UNCTAD has used in past Least Developed Countries Reports, they were geared toward developing productive capacities, expanding productive employment and increasing labour productivity, with a view to increasing national wealth and raising national living standards. A basic feature of development governance in successful developmental states was the adoption of a mixed economy model, which sought to discover the policies and institutions which could harness the pursuit of private profit to achieve national development. This Report does not romanticize the capabilities of public officials in successful countries. They were not omniscient Supermen and Bionic Women. However, competent bureaucracies were constructed in a few key strategic agencies, and state capabilities to promote development were built up through a continuous process of policy learning about what worked and what did not work. Governments also did not devise policies in a topdown fashion, but in close cooperation and communication with the business sector. The whole process was driven by a developmentally-oriented leadership of politicians and bureaucrats committed to achieving a development vision for society rather than personal enrichment and perpetuation of their own privileges. The political legitimacy of this visionary group was rooted in a social contract, in the sense that the aims of the developmentalist project were broadly shared within society and there was societal mobilization behind the goals of the project. The risks, costs and benefits of structural transformation were shared amongst the different groups of society. Building a new developmental state which is capable of meeting the challenges of the twenty-first century will involve: • Giving greater emphasis to the role of knowledge in processes of growth and development. This directs attention to the important role of knowledge systems and national innovation systems, alongside financial systems, as critical institutional complexes in the development process; 12 • Considering how to promote economic growth and structural transformation through a type of diversification which does not rely solely on industrialization. In this regard, there is a need to shift from economic activities characterized by decreasing returns to those characterized by increasing returns; • Exploring how to make better use of the opportunities of interaction between domestic and foreign capital by increasing the developmental impact of FDI and upgrading through links with global value chains; and • Adopting a regional approach to developmentalism which exploits potential for joint action to create the conditions for structural transformation The new developmental state should also move away from the authoritarian practices that have been associated with some East Asian developmental success stories. It is possible in this respect to draw on other types of developmental state, including for example the Nordic model or the Celtic Tiger. Building democratic developmental states should involve, in particular, ensuring citizens’ participation in development and governance processes. What this means is greater emphasis on deliberative democratic approaches in which people and their organizations interact to solve common problems and create new development opportunities. One positive feature of successful developmental states in the past was that governments used a range of practices to encourage and animate the private sector to act in ways which were designed to support a development transformation. The successful developmental states were not high “tax-andspend” governments. Rather, they fulfilled four major functions which sought to catalyse the creative powers of markets: (a) providing a developmental vision; (b) supporting the development of the institutional and organizational capabilities of the economic system, including developing entrepreneurs and building the government’s own capabilities; (c) coordination of economic activities to ensure the co-evolution of different sectors and different parts of the economic system; and (d) conflict management. The twenty-first century developmental state should continue to use a wide range of governance mechanisms and modalities within a mixed economy model to harness private enterprise to achieve a national development vision. In doing this, it is now possible to apply new thinking on “modern governance”, which advocates that governments promote multiple forms of two-way interaction between public and private actors. In this respect, development problems will be addressed not simply through the formal and impersonal procedures of the 13 market — or top-down, ex ante goal-setting of hierarchical governance — but also through continuing reflexive procedures, in which different actors in networks identify mutually beneficial joint projects, refine and redefine them as they monitor how far they are being achieved, and respond to changes in the external environment. The new developmental state is also likely to adopt a wide array of policy instruments which goes beyond a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Instead, a mix of policy instruments which are appropriate for the particular context should be selected, with the state more or less involved and with different degrees of compulsion and voluntary action in the way in which outcomes are achieved. Some development governance priorities for LDCs Development governance should be at the heart of the LDC response to the global financial crisis. There is no unique optimal model which is applicable to all countries; responses must be tailored to country circumstances. However, the present Report recommends that most LDCs should adopt sector-specific development policies to promote agricultural productivity growth and industrial transformation. This should encompass both developmental agricultural policies and developmental industrial policies. The Report also recommends that these sectoral policies should be supported by a more growth-oriented macroeconomic policy. The positive interplay between a growth-oriented macroeconomic policy and the sectoral policies — which improve meso-level and micro-level capabilities, incentives, institutions and infrastructure — is vital for sustained development success and substantial poverty reduction. These policies should aim to develop the domestic productive capacities of the LDCs. Such policies would serve not only to mitigate the short-term impact of the crisis, but also propel the LDCs on a different development trajectory for the post-crisis era, a trajectory which is more dynamic, more resilient, more inclusive and less dependent. This is necessary to prevent future exposure to external shocks and externally-generated crises. Possible policy directions for macroeconomic policy, agricultural policy and industrial policy are discussed in the next three sections of this overview, whilst the last section takes up the issue of priorities in an institutional reform agenda to build developmental state capabilities for good development governance. 14 3. Meeting the macroeconomic challenges For much of the last three decades, macroeconomic policies in the LDCs have been strongly influenced by the recommendations of the international finance institutions and bilateral aid donors. Typically, the main recommendations have been that monetary policy focuses on containing inflation and creating an environment for private investment, and fiscal policy should ensure that fiscal deficits remain below 3 per cent of GDP. Public investment has generally not been seen as having an important role in promoting economic development and structural change. Behind this policy stance were fears of inflation. This was significant in the 1980s and 1990s. However, inflation has not been a special problem in most LDCs during the current decade. Moreover, the source of past inflation has usually been structural rather than due to loose monetary policies. Worries that the excessive government spending could ”crowd out” private investment and fuel inflation are an unlikely outcome in countries where there is widespread under-utilization of all resources. The contention of this policy was that liberalization of trade and finance, privatization and minimization of government intervention in the economy would provide the spur to private sector development and hence sustained growth. As argued in previous editions of this Report, the reforms based on this approach have largely failed to develop the private sector as the driving force for development. The present Report argues for a marked change in the approach to macroeconomic policies in the LDCs and for one that recognizes that government has a vital role to play in restructuring the economy and in creating the conditions for a “takeoff” into sustained growth. Since economic development is about societal transformation — it is not just a technical economic problem to be left to economists — governments must also act to ensure that the costs and benefits of adjustment are distributed in an equitable and socially acceptable manner. Failure to do so would likely produce social unrest and a general backlash against necessary reforms. Public investment — especially but not exclusively in traditional infrastructure such as transport, irrigation and energy networks — has a key role to play in driving the development process. This has tended to deteriorate in recent years as ODA has been more directed toward social issues. Social concerns are important, but if progress on these is made at the expense of needed public investment in production sectors and economic infrastructure, 15 the basis for sustained growth will be undermined. Given the severity of the current economic crisis, LDC governments will be faced with rising fiscal deficits as they try to maintain domestic demand and if they also attempt to boost infrastructure investments. These deficits will need to be accommodated over the short-to-medium term in order to mitigate increased hardship for the population and to keep development programmes on track. Given the limited alternative sources of finance, ODA will be critical in enabling these objectives to be met. LDC governments will still have to explore innovative ways of raising revenue, but they need to do so in ways that avoid regressiveness, and which take account of the still-limited administrative capabilities of the state. Excessive reliance on monetary policy as a source of macroeconomic stability limits the effectiveness of monetary policy beyond price stabilization, owing to the underdeveloped state of financial institutions and the absence of viable bond markets. LDCs are generally faced with structurally high real rates of interest that are simply not conducive to an investment-driven growth path. For most of these countries, the credit crunch is more of a chronic condition than a consequence of the global banking crisis. The dramatic effects of a credit shortage have become apparent in rich countries in the current financial crisis. But this is actually a picture of everyday business life in LDCs. Monetary policy in LDCs should focus on supporting investment-focused fiscal policy, and one way to ensure this would be to have the central banks cooperate more closely with other departments of state in developing and promoting the overall economic development programme of their countries. As we argued in the Least Developed Countries Report 2006, addressing the weaknesses of domestic financial institutions should be a priority in a strategy to develop productive capacities. Another key support for an investment-driven strategy is to manage the exchange rate and, as a corollary, the capital account of the balance of payments. The current orthodoxy of floating rates, usually combined with monetary policy focused on inflation targets, has increased exchange rate volatility and frequently undermined domestic macroeconomic stabilization efforts. Managing the exchange rate — through a managed float or an adjustable peg, for example — requires resources and policy capabilities. However, it allows greater macroeconomic policy options. There is no single model of exchange rate management applicable to LDCs, but there is increasing consensus that the extreme solution of purely floating or totally fixed pegs do not work. Managing 16 the exchange rate — through a managed float or an adjustable peg, for example — would (a) support fiscal policy by helping to avoid a depreciation because of exaggerated fears of inflation; (b) aim to check the volatility of the rate following external shocks; and (c) seek to stabilize the exchange rate at a level that would strengthen the competitiveness of exports, especially of new products, and support the diversification of the economy. The effectiveness of capital controls in reducing highly speculative flows and exchange rate instability in the short run has been shown by previous crisis experiences in emerging market economies. Destabilizing surges of inflows and outflows of speculative capital occur suddenly and have been a regular feature of the financial system over the last 30 years, so it is important for countries to be able to deploy such controls whenever they consider it necessary. For most LDCs, the most common problem at present may be dealing with outflows of capital (including capital flight on the part of elite groups), but commodityproducing countries also experienced speculative capital inflows during the recent boom in world prices, and short-term measures may be necessary now to slow down the outflow of speculative portfolio investment. 4. Setting the agenda for agricultural policy In addition to the effects of the global economic crisis on their exports, developing countries — and especially the LDCs — suffered a severe shock in the first half of 2008 from the sharp rise in food and energy prices. There had already been a steady rise in prices from around 2000 but, between the last quarter of 2007 and the second quarter of 2008, non-fuel prices rose by some 50 per cent and crude oil prices by nearly 40 per cent. These increases pushed millions more people into hunger and poverty, provoking widespread riots and social unrest in many of the poorest countries. Prices have since fallen sharply, although at the start of 2009 they were higher than in 2005. Moreover, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has reported that local food prices in most of sub-Saharan Africa and in many countries of Asia and Central America in the first quarter of 2009 were still higher than a year earlier. 17 The food crisis of 2008, however, was in reality a sharp reminder of the precarious state of food supply in many parts of the world, not least in the LDCs, a situation that has been deteriorating for many years. Among the longerterm influences on prices has been the collision between rising food demand in some of the largest emerging market economies with a relatively inelastic response of supply. For the LDCs, the food crisis is really a chronic rather than a short-term problem, the result of low or falling levels of agricultural investment and fundamental failures of policy. It has long been UNCTAD’s judgement that an effective strategy for growth and development, based on the creation of new comparative advantages and production capacities, cannot succeed unless agriculture is made more productive. Without a significant agricultural surplus, food security will remain precarious and diversification of the national economy into manufacturing and other sectors will be undermined by rising food prices and wage costs. The medium- and long-term problems of agriculture in the LDCs are considerable: (a) decades of neglect have left productivity in decline or stagnant; (b) there are growing population pressures on the available stock of productive land; and (c) there are also increasing pressures on the supply of land for food production from climate change and from incentives to switch to the production and export of bio-fuels. It is the argument of this Report that these problems can only be tackled effectively with a significant developmental role on the part of the state. In contrast, the main thrust of the neo-liberal approach to agricultural development since the 1980s has been to diminish the role of the state and to enhance that of the private sector. Agricultural marketing boards were privatized, farm subsidies were reduced or abolished, and the functions of the state were narrowed to the provision of public goods, such as research and development and certain infrastructure investments. The overall impact of these reforms has been very mixed. As shown in the Least Developed Countries Report 2006, agricultural productivity has stagnated or declined in many LDCs. Reversing this trend will require, first, a firm commitment on the part of LDC governments to give high priority to agriculture in their development programmes and especially to increase the share of public investment in GDP. An effort at institutional reconstruction will be needed, insofar as ministries of agriculture are generally among the weakest departments of the state. Their present capacity to deliver extension services to the agricultural sector and, more generally, to play a strategic role in national development, is very limited and needs to be reversed. In some LDCs, the gaps in such services are being filled not by the private sector but by non-governmental organizations and 18 international organizations. Ministries of agriculture need to be incorporated into the central policy planning of governments for development. The rehabilitation of ministries of agriculture could well be a litmus test of an LDC government’s commitment to a revived and coherent development strategy. Agriculture is highly complicated and inter-country differences in land rights, climate, soil qualities, social structures and so on rule out any single policy prescription for all LDCs. However, a number of general points can be made, although their individual weights will vary with different national contexts. For example, land rights and systems of tenure vary widely but, in terms of general governance, the key principle is that land rights should be secure, transparent and enforceable by law. If these conditions are met, and tenure is not restricted to unreasonably short periods, the economic value of land should rise and one serious source of disincentives to raising productivity will be removed. A corollary, of course, is that a government committed to national development must act firmly against the illegal expropriation of land, a problem that has plagued many LDCs. The emphasis of this Report is on restoring an active development role to the state and on reviving public investment within a coherent policy framework. In the case of agriculture, effective state intervention will also need to be supported by effective local authorities which are in closer touch with local communities and therefore better informed about their precise needs. At the same time, however, it must be recognized that local authorities can hinder development with predatory and arbitrary behaviour towards the local population under their authority. Striking a correct balance between different levels of authority and ensuring policy coherence between them is therefore an important condition for an effective developmental state. Public investments, in turn, must be carefully targeted at key structural constraints, which may consist of poor or missing infrastructure, poor education and training, lack of small credit facilities, and so on. The essential point is that well-prepared public investments, including a careful assessment of likely linkage or multiplier effects, will crowd in private initiative and investment. In approaching the problems of agricultural underdevelopment, however, it is important not to frame the issues just in terms of farmers and crop or livestock production, but more broadly in a context of developing the “rural economy”, or rather “rural economies” in countries where the national economy is still weakly integrated. These would focus on developing clusters of interrelated activities, including various services to support the local community. Given the likely constraints on 19 governments’ finances in the foreseeable future, it will be worthwhile to look closely at possible alternative modes of financing infrastructure projects. The presence of a rural economy in a given area does not mean that it is either possible or desirable to promote a flourishing rural non-farm (RNF) economy, either through work for wages or self-employment. (The RNF economy may be defined as comprising all those non-agricultural activities which generate income to rural households, including in-kind income and remittances.) In some contexts — e.g. mining and timber processing — RNF activities are also important sources of local economic growth. For some areas, the only future might be the long-term decline of farming, accompanied by substantial outward population migration. What this implies, essentially, is that — before contemplating serious measures to promote agricultural growth and RNF intersectoral linkages in a given area — LDCs should take a hard look at agriculture in that area, examine its economics and consider what income levels it can reasonably support. Moreover, it is important for policymakers not to discriminate against people residing in rural areas. In designing economic policy, and the accompanying institutional reforms, the focus should be on generating improved incomes and living conditions for the whole population. In all cases, support and institutional measures should consider the medium- and long-term economic viability of the activities and people benefiting from intervention (sustainability), whether rural or urban, which is difficult to assess reliably, and thus vulnerable to political and pressure group manipulation. Policy for the promotion of RNF intersectoral linkages may be more a matter of attending to some well-known areas rather than advocating novel approaches. Basic points include the importance of education and of having the physical infrastructure in place. Also, the development and dissemination of appropriate technological packages aimed at emerging smallholder farmers could significantly enhance agricultural productivity. There is much to be done to resolve the credit and finance bottleneck. Fortunately, the lessons of microfinance are being learned and may provide useful lessons and application for the LDC RNF economy. Providing business support services in training, technical assistance and information is important, but it is not clear where the “best” models lie. The role of the state will be critical in this regard. Governments should, under specific conditions, become involved in seasonal finance, infrastructure provision, input supply and subsidies (to cover transaction costs), 20 land reform and extension services, to promote the growth of the sector. The need for policy space in this context cannot be overemphasized, since learning is an experimental process that is time-consuming and costly. In view of weak institutional and administrative structures, it will also be important to explore other organizations as alternatives to private enterprise and the state – such as farmers’ groups and other local cooperatives – for the organization of supplies of inputs, machinery, credit and so forth. Such collective effort can encourage productivity growth throughout the rural economy at the local level and may often be able to be developed on the basis of traditional forms of cooperation. In the present Report, we highlight seven key strategies that should govern LDC interventions to promote the development of the sector and promote inter-linkages: • Prioritize activities that are targeted at local and regional markets; • Support producers to meet market requirements; • Improve access to product and factor markets for the rural population; • Whenever relevant and feasible, encourage the development of commoninterest producer associations and cooperatives; • Develop flexible and innovative cross-sectoral institutional arrangements; • Recognize the diversity of agricultural production and adopt a subsector approach to the policy intervention, investment or development programme; and • Develop sustainability strategies from the start of any investment or development programme. LDC economies need to improve agricultural productivity and diversify their economies to create non-agricultural employment opportunities and generate intersectoral linkages. This will require a new development model focused on building productive capacities, enhancing rural–urban intersectoral linkages and shifting from commodity price-led growth to “catch-up” growth. This implies a change from static to dynamic comparative advantage, and the active application of science and technology to all economic activities. 21 5. Tailoring industrial policy to LDCs The nature of developmental industrial policy Industrial performance in most LDCs has been weak by comparative standards. Indeed, previous UNCTAD work has shown that, even during periods of strong investment and growth, the manufacturing sector in many LDCs, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, failed to take off. The market-led reforms since the debt crisis of the early 1980s have, to a large extent, failed to correct this deep-seated structural weakness. As a result, unbalanced, stagnating or declining manufacturing performance has been part of uneven and unsustainable growth in many LDCs over the last three to four decades. In most LDCs, there is very little large-scale domestic industry: i.e. the manufacturing sector is largely composed of light manufacturing and other labour-intensive activities, organized in small enterprises, including in the informal sector, often employing 20 people or less. On average, light manufacturing, low technology products accounted for over 90 per cent of all LDC manufactured exports in the 2005–2006 period (including food, drinks, garments and textiles); medium and highly manufactured exports are less than 2 per cent of total manufactured exports. This Report argues that policymakers at the national and international levels need to recognize the need for structural change in the development process of LDCs if they are to reinvigorate growth in activities characterized by increasing returns, dynamic comparative advantage and rapid technological progress. Not all economic activities are generators of such growth: for example, commodities and agricultural activities tend to be characterized by decreasing returns to scale, low productivity and low rates of formal employment. Different economic activities transmit different learning patterns and knowledge spillovers. Activities that generate dynamic growth tend to be those with the ability to absorb the innovations and new knowledge that produce increasing returns to scale. Successful growth episodes almost always entail rapid capital formation. Also, as discussed earlier, pro-investment financial and macroeconomic policies are essential parts of the policy agenda in LDCs. However, this is not enough for sustained growth. Recent research indicates that growth accelerations based on structural change and diversification have exerted an enduring impact on 22 productivity performance and economic welfare in developing countries. Increasingly, evidence suggests that mastery over an expanding range of more sophisticated products is central to the growth development process. The pertinent question is how to design a set of policies that would stimulate the transformation of LDC economies from being dominated by activities with decreasing or constant returns (agriculture) into those with increasing returns (processing and manufacturing), as was the case in Malaysia, the Republic Korea, Sweden, Taiwan Province of China and Finland. The present Report does not claim it has the solution, but draws on a variety of experiences of accelerated growth in countries that have undergone successful and rapid industrialization and thereby contributes to the knowledge of range of policy choices in LDCs. The concept “industrial policy” in the context of the LDCs should be understood in a broad definition, given the relatively small contribution of the manufacturing sector to the GDP in these economies. The need for continuous upgrading of products and processes underlies the broad objectives of a Schumpeterian transformative policy that we call the Developmental Industrial Policy (DIP), as elaborated in this Report — tailored specifically for LDCs. This Report defines a DIP as “any strategic intervention by the state that catalyses structural change and stimulates economic restructuring toward more dynamic, higher value added activities”. The objective of a proactive DIP is to enable learning to take place at the level of the firm and the market through both internal and, more importantly, external economies. This can be done by transferring skills, capabilities, accumulating knowledge and “know-how” and diffusing it throughout the society as much as possible. The function of developmental industrial policy in LDCs transcends “targeting sectors” or “picking winners”, to provide fundamental support and direction for satisfying the needs of broad sections of society and setting the terms of public–private partnerships. The standard conceptions of industrial policy are far too narrow, when applied to LDCs attempting to embark on programmes of major economic transformation. In departing from the mainstream perspective, there are several dynamic objectives the new developmental industrial policy should strive for: • Creating a dynamic domestic comparative advantage in an increasingly complex and sophisticated range of products and services; 23 • Upgrading productive capacities, in the sense of innovating to increase value added. The concept of upgrading — “making better products, making them more efficiently” — or moving into more skilled activities is critical in this context; • Building capability, decreasing social marginalization and reducing poverty through incomes and “labour market” policies, fiscal policy, entrepreneurship and technological development policies, as described in The Least Developed Countries Report 2007; • Creating conditions for full employment and inclusive growth, through a compatible combination of pro-growth macroeconomic policies and sectoral meso-policies, which include consideration of intersectoral linkages; • Creating conditions for the transformation from agrarian to post-agrarian societies; • Improving the supply of all public inputs with a view to raising labour productivity; • Facilitating diversification of natural resource activities; and • Building capacities at the firm level (learning). It is important to recognize that, in light of historical legacies, initial local conditions and surrounding international circumstances, industrial development pathways are not identical. The one-size-fits-all policy prescription of recent years is no longer feasible. Industrial policy instruments will vary according to the conditions that prevail in a given economy at a particular time, and both the form and content of industrial policy should evolve in relation to the development of market institutions, as well as the capabilities of the state itself to manage economic change and transformation. Accordingly, this Report argues that policymakers in LDCs should be given sufficient time and space to set priorities, discover which policy mix works best in meeting those priorities, and adapt their institutions and behavioural conventions to changing circumstances and evolving political and social preferences. This Report also recognizes that no industrial policy is infallible. Governments are not omniscient. They have imperfect information, and not all decisions made by governments are always rational. Governments are also subject to capture by special interests. The same criticisms, however, apply equally to the market. The key question is the costs and benefits associated with each. This Report takes the view that finding the appropriate balance between states and 24 markets is important, and that government policy is a fundamental influence on growth and industrialization. Adapting developmental industrial policy to LDCs A goal for DIP in LDCs should be to create domestic firms of varying sizes, including large firms, and to increase the size of their available markets. But this is not sufficient. It also needs to focus on (a) promoting entrepreneurship; (b) facilitating and enabling access to new technologies; (c) developing human resources; (d) general training; and (e) collecting, analysing and diffusing technical data. This approach advocates state intervention through a proactive technology policy towards the generation of productive and technological capabilities at the firm and farm levels. A mixture of general and selective policy tools is available to governments for promoting technological development. As argued by UNCTAD in 2007, such an approach needs to differentiate the different phases of development, namely between infant and mature industries. One of the priorities of industrial policy in LDCs is to create the conditions for learning, through the acquisition of technological and productive capacities. Market signals, if left to themselves, may even discourage the accumulation of technological capabilities. At the enterprise level, the state needs to invest in the accumulation of technological capabilities and to create the conditions to stimulate learning. At the national level, the state needs to find and ensure financing for technical change and innovation. Creating these conditions is a core function of the developmental industrial policy. The proposed developmental industrial policy should build firm-level capacities by generating a cumulative process of growth of commercial innovation in the business sector, until that growth becomes internalized. Policy implementation should aim at rapidly generating a critical mass of firms undertaking commercial innovation, i.e. continually introducing products and processes that are new to the country. Institutional mechanisms should be devised to ensure that sufficient financial resources are made available to encourage risk-taking activity and cover the costs of learning. This perspective shifts the role of the industrial policy towards one that focuses on facilitating assimilation through learning (copying, imitating and eventually innovating), in addition to capital accumulation. This implies that the modern form of industrial policy is indispensable for articulating the links between science, 25 technology and economic activities, through networking, collaboration and fine-tuning the learning components (education, research and development, and labour training) into an integrated development strategy. However, such interactions cannot be created by decree — they require institutions, resources and capabilities. In devising how to do this, LDCs should not simply look to the policy tools used in East Asia. Industrial policy success is not limited to East Asian newly industrialized countries, with their unprecedented and sustained growth experiences. Some form of industrial policy to promote development has been used in most economies. It has been argued that a long history of successful industrial policy in advanced economies since the nineteenth century persists. Examples include (a) the first-tier East Asian newly industrialized countries, such as Japan, Hong Kong (China), the Republic of Korea, Singapore and Taiwan Province of China; (b) the Nordic countries, such as Sweden and Finland; (c) Ireland; (d) some Latin American countries; and (e) almost all developed market economies. There are also interesting examples from South-east Asia, including Malaysia and Thailand, and both Bangladesh and Cambodia have had successful experiences in increasing manufacturing employment and value added. Beyond a few core elements, there is no single homogeneous model of state–market relations into which the appropriate industrial policy can be inserted. Each country must experiment and find the configuration of institutions and conventions that will work best in its national conditions and meet the expectations of its population. Particularly where large structural changes are involved and there is a significant level of risk and uncertainty about the sources of progress, careful experimentation with institutions and policies is needed to discover what will be effective in a particular national context, where history, culture and initial economic conditions all have important influences on the possibilities for growth and development. Given the premium on flexibility and “adaptive efficiency”, and also given the absence of universal laws of economic growth, restricting the policymaking space available to developing countries is more than likely to be counterproductive. The underlying assumption argued by this Report is that — owing to externalities, missing institutions, economies of scale and many other types of market failure — markets alone cannot be relied upon to coordinate the processes of capital accumulation, structural change and technological upgrading in a way consistent with sustainable growth and development. 26 LDCs can deploy a large menu of instruments for industrial development, including preferential treatment reflected in incentives or support targeted at building particular capabilities, a plethora of fiscal and investment incentives, as well as trade policy tools (tariffs and non-tariff barriers), subsidies, grants or loans. Most of these can be used to encourage capacity-building in the private sector and stimulate the process of economic transformation. Moreover, “newstyle” industrial policy tools — such as fiscal and investment incentives — are less susceptible to rent-seeking and more self-limiting than tariffs or quotas. Additionally, governments can facilitate this process by strengthening their domestic financial institutions, whether state-owned development banks such as the BNDES in Brazil, or privately owned credit institutions, such as Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. 6. Building developmental state capabilities in LDCs It is advisable to be realistic about the task of building capable developmental states in LDCs. Both skilled staff and financial resources are in short supply, and the constraints noted earlier on the problem of institutional reform overload in relation to “good governance” apply equally to the vision of good development governance which is being recommended here. However, one should not be too pessimistic on the basis of past experience. Firstly, from the experience of successful developmental states, it is clear that the technical capacities of their governments for promoting development were not particularly advanced at the outset. They built up developmental state capabilities over time, often through a deliberate strategy that focused in particular on improving a few strategically important public agencies. Large-scale institutional transformations, such as those being attempted in the good governance reform agenda, were not necessary to get the process going. Secondly, the limited success of recent experience of institutional reforms in LDCs is particularly related to the fact that these initiatives have often been donor-driven. The more a developmentalist project is country-owned, the easier the building developmental state capabilities should be. A pragmatic approach to building developmental state capabilities in LDCs would be a focused approach which seeks to sequentially build minimum 27 governance capabilities for achieving evolving development outcomes. This would involve the adoption of a small number of institutional reforms which have a “good fit” with the existing context. Models transferred wholesale from successful East Asian newly industrializing economies are likely to be as unsuccessful as models of good governance transferred from advanced countries. Institutional reforms will progress if (a) their outputs and outcomes meet the political demands for them; (b) there is a good fit between political capacity and technical capacity; and (c) technical competencies fit the requirements of the reform tasks. Both technical capacity and political capacity matter. Technical capacities can be built up incrementally through policy learning and institutional experimentation, focusing initially on extending the experience of islands of excellence within the public administration and executive agencies. Such a strategic incrementalist approach should aim to build governance capabilities required to relax binding constraints on the development of productive capacities. It should develop governance capabilities that support processes of capital accumulation and technological progress in sectors that are strategically important for economic development and the generation of productive employment. Islands of excellence within the ministries and executive agencies of LDCs — which are hidden by the country-wide governance indicators — can provide lessons about what works and does not work in particular contexts, and also models for spreading these practices. However, it is important that there be a competent pilot agency, close to political power, that can provide overall vision and coordination. Moreover, an institution dedicated to aid management is also critical. In terms of political capacity, a defining characteristic of successful developmental states is the existence of developmentally-oriented leadership. Unless such a leadership exists, there is no possibility of creating developmental state capabilities. If a governing elite is simply committed to personal enrichment and perpetuation of its own privileges, rather than national development, structural transformation and economic development will be impossible. This leadership will be most successful if it establishes a social compact through which broad sections of society support the development project. This should include both rural and urban interests and thus developmental policies should include both developmental agricultural policies and developmental industrial policies. A final important ingredient is the development of growth 28 coalitions. These arise when relations between business and government elites take the form of active cooperation towards achieving the goals of fostering investment and technological learning, and increasing productivity. LDC governments should use the financial crisis as a moment to build positive growth coalitions between governments and the domestic business community. Finally, it is important to note that, without the support of LDC development partners for a domestically-owned developmentalist project, that project will be very difficult to realize. Firstly, policy space is necessary, to allow policy pluralism and experimentation, which are necessary conditions for developmental success. Adhesion to international agreements, policy conditionalities attached to aid and close guidance by donors should not undermine the policy learning critical to building developmental state capabilities. Secondly, the formation of domestic growth coalitions can be stymied if aid is more oriented to donor concerns than to building up domestic business. Paradoxically, although past policies have been ostensibly focused on private sector development, the private sector remains very weak in most LDCs. It is vital therefore that aid support the formation of growth coalitions. Thirdly, domestic financial resource constraints also mean that donor support will be necessary to build developmental state capabilities. Development partners can best support genuine country ownership in LDCs, and also achieve mutual goals, by supporting the realization of national developmental aspirations. Approximately 20 per cent of aid to LDCs now goes to improve government capabilities. This aid should be refocused from the current good governance institutional reforms towards promoting good development governance and building developmentally-capable states in LDCs. * * * The basic message of this Report is that LDC governments should view the global economic crisis as an opportunity for a turning point in their development path. They need to shift towards a catch-up growth strategy based on the development of productive capacities and expansion of productive employment opportunities. The Report argues that LDC governments have a vital role to play in the restructuring of their economies, and in creating conditions for catch-up growth. It is high time to inject a developmental dimension into the good governance agenda. LDC policymakers need to be more cognizant and 29 informed of the policy options that exist and have been used successfully in other cases of accelerated growth and structural transformation. The Report is intended to contribute to this process and increase the capacity of LDCs to govern developmentally. The development partners and the international community should support the LDCs in their quest for good development governance. The crisis demands that it is time to catch up, by broadening and adapting public action to conditions suitable for small, open-market developing economies. Historical evidence suggests that this objective is achievable. This Report sketches out a concrete alternative economic strategy and a fresh agenda for LDC policymakers that include institutional capacity-building and the strengthening of the market-complementing developmental state. Dr. Supachai Panitchpakdi Secretary-General of UNCTAD 30