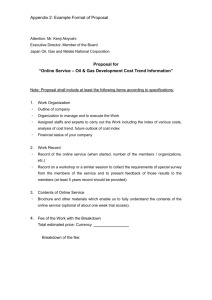

MSA Section 78(3) to Assess Alternative Service Delivery Options RFP NO: 554C/2008/09

advertisement