Document 10383798

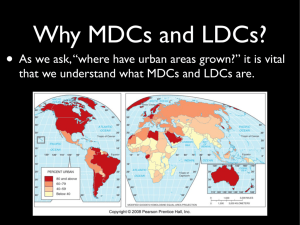

advertisement