SCHOOL UNIFORM DESIGN PREFERENCES OF UNIFORM WEARERS AND Angela Uriyo

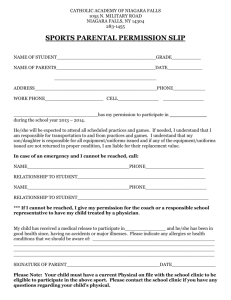

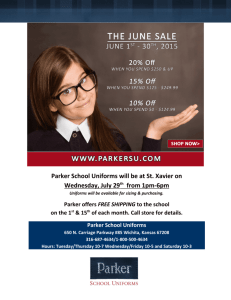

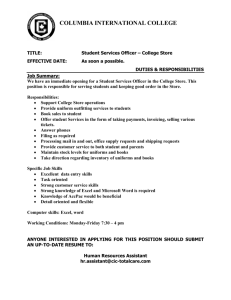

advertisement