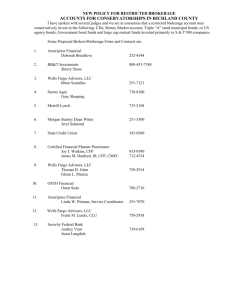

Conflicts of Interest, Regulations, and Stock Recommendations

advertisement