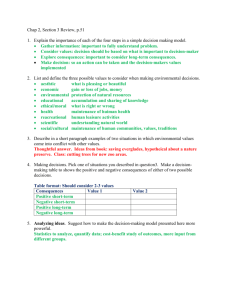

Canadian Cost-Benefit Analysis Guide Regulatory Proposals Interim

advertisement