Fair Trade and Free Entry:

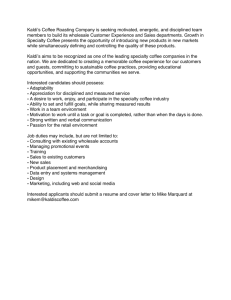

advertisement