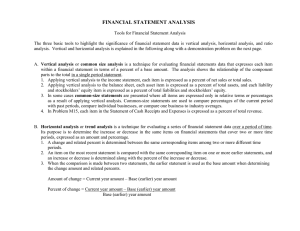

5 Introduction to Financial Statement Analysis c

advertisement