The Design and Implementation of Subsidies for Housing Finance

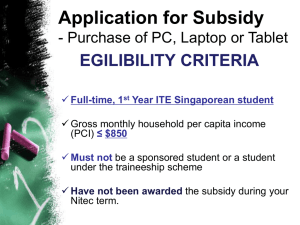

advertisement