Foreign Exchange Markets

advertisement

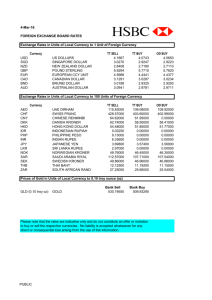

Foreign Exchange Markets Rajesh Chakrabarti* Introduction During 2003-04 the average monthly turnover in the Indian foreign exchange market touched about 175 billion US dollars. Compare this with the monthly trading volume of about 120 billion US dollars for all cash, derivatives and debt instruments put together in the country, and the sheer size of the foreign exchange market becomes evident. Since then, the foreign exchange market activity has more than doubled with the average monthly turnover reaching 359 billion USD in 2005-2006, over ten times the daily turnover of the Bombay Stock Exchange. As in the rest of the world, in India too, foreign exchange constitutes the largest financial market by far. Liberalization has radically changed India’s foreign exchange sector. Indeed the liberalization process itself was sparked by a severe Balance of Payments and foreign exchange crisis. Since 1991, the rigid, four-decade old, fixed exchange rate system replete with severe import and foreign exchange controls and a thriving black market is being replaced with a less regulated, “market driven” arrangement. While the rupee is still far from being “fully floating” (many studies indicate that the effective pegging is no less marked after the reforms than before), the nature of intervention and range of independence tolerated have both undergone significant changes. With an overabundance of foreign exchange reserves, imports are no longer viewed with fear and skepticism. The Reserve Bank of India and its allies now intervene occasionally in the foreign exchange markets not always to support the rupee but often to avoid an * College of Management, Georgia Tech, 800 West Peachtree Street, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA. Email: rajesh.chakrabarti@mgt.gatech.edu . 1 appreciation in its value. Full convertibility of the rupee is clearly visible in the horizon. The effects of these development s are palpable in the explosive growth in the foreign exchange market in India. Foreign Exchange Markets in India – a brief background The foreign exchange market in India started in earnest less than three decades ago when in 1978 the government allowed banks to trade foreign exchange with one another. Today over 70% of the trading in foreign exchange continues to take place in the inter-bank market. The market consists of over 90 Authorized Dealers (mostly banks) who transact currency among themselves and come out “square” or without exposure at the end of the trading day. Trading is regulated by the Foreign Exchange Dealers Association of India (FEDAI), a self regulatory association of dealers. Since 2001, clearing and settlement functions in the foreign exchange market are largely carried out by the Clearing Corporation of India Limited (CCIL) that handles transactions of approximately 3.5 billion US dollars a day, about 80% of the total transactions. The liberalization process has significantly boosted the foreign exchange market in the country by allowing both banks and corporations greater flexibility in holding and trading foreign currencies. The Sodhani Committee set up in 1994 recommended greater freedom to participating banks, allowing them to fix their own trading limits, interest rates on FCNR deposits and the use of derivative products. The growth of the foreign exchange market in the last few years has been nothing less than momentous. In the last 5 years, from 2000-01 to 2005-06, trading volume in the foreign exchange market (including swaps, forwards and forward cancellations) has more 2 than tripled, growing at a compounded annual rate exceeding 25%. Figure 1 shows the growth of foreign exchange trading in India between 1999 and 2006. The inter-bank forex trading volume has continued to account for the dominant share (over 77%) of total trading over this period, though there is an unmistakable downward trend in that proportion. (Part of this dominance, though, result s from double-counting since purchase and sales are added separately, and a single inter-bank transaction leads to a purchase as well as a sales entry.) This is in keeping with global patterns. [Figure 1 about here] In March 2006, about half (48%) of the transactions were spot trades, while swap transactions (essentially repurchase agreements with a one-way transaction – spot or forward – combined with a longer- horizon forward transaction in the reverse direction) accounted for 34% and forwards and forward cancellations made up 11% and 7% respectively. About two-thirds of all transactions had the rupee on one side. In 2004, according to the triennial central bank survey of foreign exchange and derivative markets conducted by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS (2005a)) the Indian Rupee featured in the 20th position among all currencies in terms of being on one side of all foreign transactions around the globe and its share had tripled since 1998. As a host of foreign exchange trading activity, India ranked 23rd among all countries covered by the BIS survey in 2004 accounting for 0.3% of the world turnover. Trading is relatively moderately concentrated in India with 11 banks accounting for over 75% of the trades covered by the BIS 2004 survey. Features of the Forward premium on the Indian rupee 3 The Indian rupee has had an active forward market for some time now. The forward premium or discount on the rupee (vis-à-vis the US dollar, for instance) reflects the market’s beliefs about future changes in its value. The strength of the relationship of this forward premium with the interest rate differential between India and the US – the Covered Interest Parity (CIP) condition – gives us a measure of India’s integration with global markets. The CIP is a no-arbitrage relationship that ensures that one cannot borrow in a country, convert to and lend in another currency, insure the returns in the original currency by selling his anticipated proceeds in the forward market and make profits without risk through this process. Chakrabarti (2006) reports tha t between late 1997 and mid-2004 the average discount on the rupee was about 4% per annum. During the period the average difference between 90-180 day bank deposit rates in India and the inter-bank USD offer rate was about 4.5% for 3-months and 3.5% for the 6- months period. With these two figures in the same ballpark (particularly given that bank deposit rates and inter-bank rates are not strictly comparable), annual averages of interest rate differences and the forward exchange premium also indicate a moderate degree of co- movement between the two variables. The interest rate differential explains about 20% of the total variation in the forward discount. The deviation of the Indian rupee-US dollar from the covered interest parity, however, exhibits long-lived swings on both sides of the zero line. This would indicate arbitrage opportunities and market imperfections provided we could be sure of the comparability of the interest rates considered. Therefore, while the behavior of the forward premium on the Indian rupee is broadly in lines with the CIP, more careful empirical analysis involving directly comparable interest rates is necessary to measure 4 the strength of the covered interest parity condition and the efficiency of the foreign exchange market. Under market efficiency, the forward exchange rate is considered to be an unbiased predictor of the future spot rate, with random prediction errors. While the prediction errors of forward rates on the rupee appear to show some degree of persistence, any conclusion in this matter too must await more rigorous analysis. Intervention in Foreign Exchange Markets The two main functions of the foreign exchange market are to determine the price of the different currencies in terms of one another and to transfer currency risk from more risk-averse participants to those more willing to bear it. As in any market essentially the demand and supply for a particular currency at any specific point in time determines its price (exchange rate) at that point. However, since the value of a country’s currency has significant bearing on its economy, foreign exchange markets frequently witness government intervention in one form or another, to maintain the value of a currency at or near its “desired” level. Interventions can range from quantitative restrictions on trade and cross-border transfer of capital to periodic trades by the central bank of the country or its allies and agents so as to move the exchange rate in the desired direction. In recent years India has witnessed both kinds of intervention though liberalization has implied a long-term policy push to reduce and ultimately remove the former kind. It is safe to say that over the years since liberalization, India has allowed restricted capital mobility and followed a “managed float” type exchange rate policy. 5 During the early years of liberalization, the Rangarajan committee recommended that India’s exchange rate be flexible. Officially speaking, India moved from a fixed exchange rate regime to “market determined” exchange rate system in 1993. The overt objective of India’s exchange rate policy, according to various policy pronouncements, has been to manage “volatility” in exchange rates without targeting any specific levels. This has been hard to do in practice. The Indian rupee has had a remarkably stable relationship with the US dollar. Meanwhile the dollar appreciated against major currencies in the late 90’s and then went into an extended decline particularly during 2003 and 2004. The lock-step pattern of the US dollar and the Rupee is best reflected in the movements in the two currencies against a third currency like the Euro. The correlation of the exchange rates of the two currencies against the Euro during 1999-2004 was 0.94. Several studies have established the pegged nature of the rupee in recent years (see Chakrabarti (2006) for a more detailed discussion). Based on volatility, India had a de facto crawling peg to the US dollar between 1979 and 1991 which changed to a de facto peg from mid-1991 to mid-1995, with a major devaluation in March 1993. From mid-1995 to end-2001, the rupee reverted to a crawling peg arrangement in practice. An analysis of the ratio of the variance of the exchange rate to the sum of the variances of the interest rate and the foreign exchange reserves reveals a move even closer to the fixed exchange rate system. A comparison of the sensitivity (beta) of the Dollar-rupee rate with the Euro-rupee rate for a three year period (1999 through 2001), indicates that India had a dollar beta of 1.01 – tenth highest among the 53 countries considered. More importantly, the US dollar-Euro exchange rate explained about 97% of all movements in the Indian rupee-Euro exchange rate – highest 6 among all the 53 countries considered. Clearly the Indian rupee has been an excellent “tracker” of the US dollar. It is instructive to consider the Rupee-Dollar exchange rate in the light of the purchasing power parity (PPP) holding that the exchange rate between two currencies should equal the ratio of price levels in two countries. In its dynamic form PPP holds that that the rate of depreciation of a currency should equal the excess of its inflation rate to that in the other country. Over a reasonably long period of time, the devaluation in the Indian Rupee, vis-à-vis the US dollar does seem to have an association with the difference in the inflation rates in the two countries. Between 1991 and 2003, the two variables have had visible co- movements with a correlation of about 0.57 (Chakabarti (2006)). This may be a result of Indo-US trade flows dominating the exchange rate markets but it is perhaps more likely that it reflects the exchange rate management principles of the monetary authorities The Reserve Bank of India has used a varied mix of techniques in intervening in the foreign exchange market – indirect measures such as press statements (sometimes called “open mouth operations” in central bank speak) and, in more extreme situations, monetary measures to affect the value of the rupee as well as direct purchase and sale in the foreign exchange market using spot, forward and swap transactions (see Ghosh (2002)). Till around 2002, the measures were mostly in the nature of crisis management of saving-the-rupee kind and sometimes the direct deals would be repeated over several days till the desired outcome was accomplished. Other public sector banks, particularly the SBI often aided or veiled the intervention process. 7 The exact details of the interventions are shrouded in mystery, not unusual for central banks ever wary of disclosing too much of their hand to the currency speculators. The Tarapore Committee report had urged more transparency in the intervention process and recommended, in 1997, that a ‘Monitoring Exchange Rate Band’ of ± 5% be used around an announced neutral real effective exchange rate (REER), with weekly publication of relevant figures, something yet to be implemented. In a recent survey on foreign exchange market intervention in emerging markets, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS (2005b)) found that out of 11 emerging market countries considered, India gave out most complete information on intervention strategy (along with three others); no information on actual interventions (five others did the same) and did not cover foreign exchange intervention in annual reports (like two other countries). On the whole it ranked fourth most opaque in matters of foreign exchange intervention among the eleven countries compared. Regulation of cross-border currency flows A feature of the economy that is intricately related with the exchange rate regime followed is the freedom of cross-border capital flows. This relationship comes from the so-called “impossible trinity” or “trilemma” of international finance, which essentially states that a country may have any two but not all of the following three things – a fixed exchange rate, free flow of capital across its borders and autonomy in its monetary policy. Since liberalization, India has been having close to a de facto peg to the dollar and simultaneously has been liberalizing its foreign currency flow regime. 8 Close on the heels of the adoption of market determined exchange rate (within limits) in 1993 came current account convertibility in 1994. In 1997, the Tarapore committee, on Capital Account Convertibility, defined the concept as “the freedom to convert local financial assets into foreign financial assets and vice versa at market determined rates of exchange ” and laid down fiscal consolidation, a mandated inflation target and strengthening of the financial system as its three main preconditions. Meanwhile capital flows have been gradually liberalized, allowing, on the inflow side, foreign direct and portfolio investments, and tapping foreign capital markets by Indian companies as well as considerably better remittance privileges for individuals; and on the outflow side, international expansion of domestic companies. In 2000, the infamous Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA) was replaced with the much milder Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) that gave participants in the foreign exchange market a much greater leeway. The ultimate goal of capital account convertibility now seems to be within the government’s sights and efforts are on to chalk out the roadmap for the last leg, though it is not expected to be accomplished before 2009. Expectedly, the wisdom of the move has been hotly debated . Advocates of convertibility cite the “consumption smoothing” benefits of global funds flow and point out that it actually improves macroeconomic discipline because of external monitoring by the global financial markets. Convertibility can spur domestic investment and growth because of easier and cheaper financing. It can also contribute to greater efficiency in the banking and financial systems. On the other hand, skeptics like Williamson (2006), for instance, points out that India is yet to fulfill at least one of the three major preconditions to Capital Account Convertibility set out by the 9 Tarapore committee, viz. fiscal discipline, with a public sector deficit of 7.6% of the GDP and the ratio of public debt to GDP of over 83% in 2005-06. In any case, the argument goes, the benefits of convertibility do not necessarily outweigh the risks and cross-border short-term bank loans – usually the last item to be liberalized – are the most volatile. It is generally held that it was, in fact, the lack of convertibility that protected India from contamination during the Asian contagion in 1997-98. The Dynamics of Swelling Reserves An important corollary of India’s foreign exchange policy has been the quick and significant accumulation of foreign currency reserves in the past few years. Starting from a situation in 1990-91 with foreign exchange reserves level barely enough to cover two weeks of imports, and about $32 billion at the beginning of 2000, India’s foreign exchange position rocketed to one of the largest in the world with over $155 billion in mid-2006. Since 2000, this implies a compounded annual growth rate of about 28% with the years 2003 and 2004 having the most stunning rises at 48% and 45% respectively. During these two years the US dollar fell against the Euro by 19% and against the rupee by 9%. Without RBI intervention, the latter figure is likely to have been larger and the reserves accumulation less spectacular. A sizable foreign exchange reserve acts as liquidity cover and protects against a run on the country’s currency, and reduces the rate of interest on Indian debt in the world market by lowering the country risk perception by international rating agencies. However, beyond a point, it begins to affect the money supply in the country, and interest rates. There are significant “sterilization costs” to avoid this and the RBI loses money by 10 earning low returns on the safe assets used to park the reserves. Given this low rate of return, there has been discussion about the unique proposal to use part of the reserves to fund infrastructure projects. Outlook Liberalization has transformed India’s external sector and a direct beneficiary of this has been the foreign exchange market in India. From a foreign exchange-starved, control-ridden economy, India has moved on to a position of $150 billion plus in international reserves with a confident rupee and drastically reduced foreign exchange control. As foreign trade and cross-border capital flows continue to grow, and the country moves towards capital account convertibility, the foreign exchange market is poised to play an even greater role in the economy, but is unlikely to be completely free of RBI interventions any time soon. 11 References Bank for International Settlements, 2005a. Triennial Central Bank Survey: Foreign exchange and derivatives market activity in 2004, Basel, Switzerland. Bank for International Settlements, 2005b. Foreign exchange market intervention in emerging markets: motives, techniques and implications, BIS Paper No.24, Basel, Switzerland. Chakrabarti, Rajesh, 2006. The Financial Sector In India: Emerging Issues, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2006. Ghosh, Soumya Kanti, 2002. RBI Intervention in the Forex Market: Results from a Tobit and Logit Model Using Daily Data, Economic and Political Weekly, June 15, pp.2333-2348. Williamson, John, 2006, Why Capital account Convertibility in India is Premature, Economic and Political Weekly, May 13, pp.1848-1850. 12 May-99 * Not corrected for double counting Source: RBI Bulletins 13 Time February-06 November-05 August-05 May-05 February-05 November-04 August-04 May-04 February-04 November-03 August-03 May-03 February-03 November-02 August-02 May-02 February-02 November-01 August-01 May-01 February-01 November-00 August-00 May-00 February-00 November-99 August-99 Monthly forex trade in billion USD (including derivatives and fwd cancellations) Fig. 1: Forex Trading activity 600 Inter-bank trade volume* 500 Merchant trade volume 400 300 200 100 0