PLANT & PEST ADVISORY L , N & T

advertisement

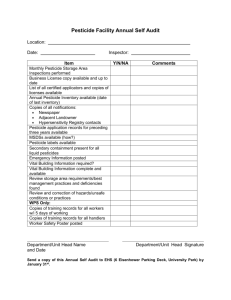

RUTGERS COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AT THE NEW JERSEY AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION PLANT & PEST ADVISORY LANDSCAPE, NURSERY & TURF EDITION $1.50 MARCH 7, 2002 Think of Water from a Plant Disease Perspective Ann Brooks Gould, Ph.D., Plant Pathology and Margery Daughtrey, Cornell University, Senior Extension Associate T he balance among the microorganisms that cause disease (called pathogens), their host plants, and the environment ultimately determines whether a disease will develop. The environmental factor that has the most impact on plant disease development is moisture. Living organisms consist chiefly of water, so the uptake of water is critical if organisms, both plant pathogens and their hosts, are to grow. The Role of Water in Plant Disease Development INSIDE Think of Water from a Plant Disease Perspective ................... 2 NJDEP Drought Information ... 2 Rutgers Lab Services ................. 2 Plant & Pest Advisory 2002 Schedule ............................. 2 Rhabdocline Needlecast of Douglas Fir ............................. 3 DEP Changes Pesticide Regulations ................................. 3 NOFA Announces First-Ever Standards for Organic Land Care .................................... 5 Nursery & Greenhouse Film Recycling ..................................... 5 From a host perspective, too little water in the soil (drought stress) or too much soil moisture (which leads to oxygen deprivation) places plants under stress, and plants with water stress are more susceptible to disease. Water is also important to facilitate movement of nutrients from the roots to aerial plant parts, as well as sugars, made in the leaves during photosynthesis, to the roots. Thus, any environmental condition or disease (such as a vascular wilt or root rot) that impedes the flow of water in the vascular system also places undue stress on the host. Symptoms of plants with long-term water stress (at either extreme) include leaf wilt, yellowing, scorch, or premature drop, a decline in vigor, progressive branch dieback, and eventual death. From a pathogen perspective, moisture extremes have a similar impact. Although too much water in the soil deprives pathogens of oxygen, too little water impedes pathogen survival and the infection process. Free moisture on leaf or root surfaces is necessary for germination, penetration, and dispersal of fungal spores to new hosts. Indeed, most pathogenic fungi grow best in a damp environment. Powdery mildews are a notable exception, thriving in humid rather than wet conditions. Pathogenic fungi secrete enzymes into leaf or root tissues to macerate, or soften up, host cells, releasing nutrients that are taken up by the fungus as food. Free moisture is needed to help move the enzymes out of the fungus and to let the nutrients flow back in. Some species of fungi with very thin walls require a continuous supply of water to prevent desiccation. Water is also important for the infection process, which is a series of steps that includes spore germination, penetration through the host SEE WATER AND DISEASE ON PAGE 2 VOL. 8 NO. 1 PAGE 1 New Jersey DEP Drought Information New Jersey Drought Webpage www.njdrought.org New Jersey Drought Hotline 1-800-448-7379 Fax: 609-633-1495 3/7/02 - Drought emergency in effect throughout entire state. No water restrictions issued. ‘Region specific’ restrictions will be announced early next week. ❏ Rutgers Lab Services ❖ The Plant Diagnostic Laboratory and Nematode Detection Service provides accurate and timely diagnoses of plant problems. For sample submission instructions and forms, visit our web site at: http://www.rce.rutgers.edu/ plantdiagnosticlab/submissions.html. Forms may also be obtained from your local county Rutgers Cooperative Extension office or via fax request (732/9321270). ❖ The Rutgers Soil Testing Laboratory performs chemical and mechanical analyses of soils. For More Information please write or call us: Rutgers Soil Testing Laboratory, P.O. Box 902, Milltown, NJ 08850, 732/932-9295, Fax: 732/932-9292 or visit us on the web at: http://www.rce.rutgers.edu/soiltestinglab/ index.html. ❏ Plant & Pest Advisory 2002 Schedule T hank you for subscribing to the Plant & Pest Advisory. The Landscape, Nursery & Turf edition will be published biweekly on Thursdays for the 2002 growing season from March 7 to August 22, with monthly issues from September to November. ❏ PAGE 2 WATER AND DISEASE FROM PAGE 1 epidermis, and fungal growth within the plant tissues. The pathogen can be particularly vulnerable to drying while it is in the process of trying to infect the plant. For aerial plant pathogens, free moisture and high relative humidity is important for infection of leaf and other above-ground tissues (such as petals, stems, branches, or fruit). This process requires a period of continuous leaf wetness, and this “duration of leaf wetness” varies with the fungus. For example, spores of Venturia inaequalis, the pathogen that causes apple scab, require 9 hours of continuous leaf wetness to infect leaves and fruit. It stands to reason, therefore, that irrigation strategy and amount of natural rainfall would have a great impact on the development of this disease. For fungi that attack roots, free moisture is also required for the infection process. In addition, water in soil pores is needed for the motile spores (called zoospores) produced by a group of common soil pathogens (the water molds) to swim toward healthy roots. Finally, moisture, in the form of rain, splashing, and running water, is important for the dispersal of spores of all kinds of fungi to the roots or foliage of new hosts. Managing Water in the Nursery: The clue is to think like a plant and a spore! Moisture management in the nursery is important from both a plant health and a pathogen point of view. Too much or too little moisture during production can have equally devastating results. Some points to keep in mind include: ● As a rule, avoid prolonged periods of leaf wetness. If using overhead irrigation, water to minimize the length of time foliage stays wet. Water during early morning hours or water during warmer, breezier periods when rapid drying is likely to occur. Consider using drip irrigation or aimed microemitters that do not place moisture on foliar surfaces. ● Avoid excess moisture in potting mix. In addition to its harmful effects on the host, too much water promotes the activity of both water mold (e.g., Pythium and Phytophthora) and non-water mold (e.g., Rhizoctonia, Fusarium, and Thielaviopsis) soil pathogenic fungi. Excess water is also conducive to the growth of anaerobic bacteria which produce by-products that are toxic to plant roots. ● Use a balanced potting mix with properties of aeration and moisture retention that are appropriate to the size of the container. In mixes that do not drain well, a perched water table is created at the bottom of the container, which encourages the growth of microorganisms and pathogens and deprives roots of oxygen. ● When using hydrophobic components in mix, such as ground bark or peat, avoid extreme drying of the pot. Rewetting such mixes is difficult; water from overhead sprinklers simply channels around the rootball and drains away. ● Some woody ornamentals are prone to edema. Edema, or corky, blister-like outgrowths on the lower surface of leaves, occurs during cloudy periods with abundant moisture. In such conditions, when more water is supplied to leaf tissues than is lost during transpiration, the cells that line leaf stomates (where gas exchange occurs) become too full and burst. Ornamentals especially prone to edema are Camellia, Hedera, Hibiscus, Ligustrum, Pittosporum, and Taxus. ● Diseases (particularly Phytophthora root rot) can be spread when pathogen-infested pond water is used for irrigation. Avoid using pond water if possible, and do not allow runoff water from growing areas to drain directly into irrigation ponds. ❏ VOL. 8 NO. 1 DEP Changes Pesticide Regulations Rhabdocline Needlecast of Douglas Fir Ann Brooks Gould, Ph.D., Plant Pathology W e’ve received a number of reports the past few weeks on the incidence of Rhabdocline needle cast of Douglas fir in Christmas tree plantations. The weather during the infection period in many locations last year was ideal for disease development. This disease is of great concern to Christmas tree growers in New Jersey, and with good reason. Severely affected trees lose a large portion of their needles, and this can represent a significant loss to the grower, especially on trees almost ready for sale. To diagnose Rhabdocline needlecast, look for redbrown spots surrounded by green tissue on last year’s growth. In many plantations, this symptom is evident now. A week or two before budbreak, orange fruiting bodies develop on the lower surface of affected needles. Once the fruiting bodies are mature, they rupture and release abundant spores during wet weather. Spores, which are blown by wind and rain to nearby trees, infect expanding buds. Symptoms on newly infected needles do not appear until the following fall or winter. Rhabdocline needlecast is influenced by high humidity, so lower branches, shaded branches, or branches on the northeast side of the tree are more severely affected. Trees with the disease can serve as a source of inoculum for new growth this season, so it is important to use aggressive control measures in blocks where the disease has occurred. For best results, remove old and severely infected trees now. Branches on trees that are less severely infected (less than 30% of branches affected) should also be pruned now during dry weather. If possible, a burning permit should be obtained so that infected tissue can be incinerated. Chlorothalonil (Bravo or Daconil) is labeled for control of Rhabdocline needlecast. Begin sprays when the first 10% of the trees in the planting first break bud (or the candles are about 1/2 inch long). The second spray goes on one week later, and the third spray goes on two weeks after the second spray. A fourth spray three weeks later may be necessary if rainy spring weather persists. Add a spreader sticker to enhance coverage. Other compounds labeled for control include benomyl (apply two times at 4-week intervals), Kocide (apply at 1- to 2-week intervals), Spectro (apply at 2- to 3-week intervals), or mancozeb (Junction). Refer to label for timing and rates. For all fungicides, thorough coverage is essential. For further information on Rhabdocline needlecast, refer to Rutgers Cooperative Extension fact sheet FS183, available through your county extension office. ❏ VOL. 8 NO. 1 George Hamilton, Ph.D., Pest Management I n November of 2001, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection put into place several changes to the New Jersey Pesticide Control Act. In this issue we will cover the changes that affect who must have a private applicators license to apply pesticides; how a commercial pesticide applicator license is obtained; and who must have a commercial pesticide operator registration (now referred to as a commercial pesticide operator license) to apply pesticides and how that license is obtained. Upcoming issues will cover changes regarding areawide notifcation, service vehicles, record keeping, storage areas, outdoor notification, and schools. Changes to Definition of Private Pesticide Applicator In the past, only those farmers who either applied or supervised the application of restricted use pesticides needed to have a pesticide license. The new change now requires that farmers who apply or supervise the use of any pesticide, general or restricted use, must now have a private applicator license. The only exceptions are as follows: 1. Farmers who apply pesticides under the supervision of a licensed private applicator who is employed by the same farm at the same physical location, or 2. Farmers who already have a commercial applicators license with the proper category certification(s), or 3. Farmers who apply general use pesticides to produce an agricultural commodity worth less than $2,500 annually on land that they either own or rent, or 4. Farmers who apply only “minimum risk” pesticides as defined in N.J.A.C. 7:30-2.1(m)5, or 5. Farmers who have experience in using agricultural pesticides to produce an agricultural commodity and only use general use products. This final exemption expires November 19, 2003. This new change means that even if you are applying or supervising the application of products such as carbaryl, diazinon or Bacillus thuringiensis on agricultural crops you must have a private applicators license. The implications of this change means that several grower groups, such x-mas tree growers, vineyardists and organic growers, will now have to obtain licenses if they apply or supervise the use of EPA registered pesticides. If you need to obtain a private applicators license because of the new requirement, please be aware that the process for getting a license has not changed. The first step is to obtain the “Private Applicator Manual” SEE PRIVATE APPLICATOR ON PAGE 4 PAGE 3 PRIVATE APPLICATOR FROM PAGE 3 and informational sheet explaining the procedure for signing up to take the exam from your local County Cooperative Extension office. Once you have studied the manual and are ready to take the exam follow the procedures outlined in the pamphlet to register for the exam. Changes to Obtain Commercial Pesticide Applicators License In the past, a commercial pesticide applicator license was obtained by: ● acquiring the CORE pesticide applicator training manual, and the appropriate Pesticide Applicator Category manual(s) for the type(s) of work you would do, and ● studying the manuals on your own, and ● registering to take the CORE and Category(s) exams needed for the type of work you would be doing. Once you passed the CORE and Category exams and paid the license fee, you became a licensed commercial pesticide applicator. Today, the process has been slightly changed. In addition to the items listed above, to be eligible to take the CORE exam, a prospective commercial pesticide applicator must complete a DEP approved basic pesticide training course. Once the course is completed the applicant can register and take the CORE exam. Once you have passed the CORE exam and prior to taking the required Category(s) exams the applicant must complete a minimum of 40 hours of “on the job” training sufficient to competently perform the functions of any applications the applicant may become involved with. During this period the applicant must be instructed in the recognition, biology and infestation signs of the pests to be controlled and perform or observe a minimum number of applications under the direct supervision of a licensed commercial pesticide applicator for each category the person will be licensed. The number of applications required varies depending on the type of work being performed. The only deviations from this process are as follows: ● Category 10 is exempt from “on-the-job” training requirements since training is required related to the specific category for which Category 10 applications will be made. ● Category 11 requires “on-the-job” training in aerial pest control only and is exempt from the “on-the-job” training requirements for other categories. If 40 hours of “on-the-job” training is deemed unavailable by DEP the Department may allow: ● the substitution of an internship from an approved trainer, company or school and successful completion of an approved category training course that covers the recognition, biology and infestation signs of the pests to be controlled, or ● submission of an affidavit attesting to proof of one year of work experience in the category desired. If 40 hours of “on-the-job” training or an internship is deemed unavailable by DEP the Department may allow successful completion of a DEP approved correspondence course or on-line interactive computer course to satisfy the training requirements. Once the “on-the-job” training is completed, the applicant can register to take the required category exam(s) by submitting the required application form complete with proof of successful completion of the “on-the-job” training. Changes to Commercial Pesticide Operator Registrations In the past, a commercial pesticide operator license was needed to apply general or restricted use pesticides unless: ● the person was a licensed commercial pesticide applicator, or ● the person worked under the direct supervision of a licensed commercial pesticide applicator that was always present at the application site. Today, in addition to the exclusions listed above, an operator license is not needed if the person is: ● applying pesticides denoted as “minimum risk” by EPA under 40 CFR 152, or ● exempted under N.J.S.A. 13:1F-1a. Examples of this exception includes municipal or county inspectors who use only general use pesticide as flushing agents, such as pyrethrum sprays, to check for insect infestations during the normal course of their job. DEP has also changed the process for obtaining a commercial operator license. In the past, a form was filled out by the applicant and his licensed supervisor that certified the applicant had had the necessary training to become a commercial pesticide operator. Today, anyone who wishes to become licensed as a commercial pesticide operator and has never been so before must: 1. complete a DEP approved commercial pesticide operator training course, and 2. complete a minimum of 40 hours of “on the job” training sufficient to allow the operator to competently perform the functions of a commercial pesticide operator. During this period the operator must perform or observe a minimum number of applications under the direct supervision of a licensed commercial pesticide applicator. The number of applications required varies depending on the type of work being performed. Once the approved commercial pesticide operator training course is completed, the operator can apply to DEP for a commercial pesticide operator license by submitting a completed Operator Application Form to DEP. Applications for commercial pesticide operator SEE COMMERCIAL OPERATOR ON PAGE 5 PAGE 4 VOL. 8 NO. 1 NOFA Announces First-Ever Standards for Organic Land Care October, 2001 Press Release o help meet the growing demand for organic lawn and yard care, the Massachusetts and Connecticut Chapters of the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA) have created Standards for Organic Land Care: Practices for Design and Maintenance of Ecological Landscapes. The NOFA Standards are the first of their kind, and are expected to become a model for organic land care throughout the United States. The NOFA Organic Land Care Committee, consisting of land care professionals, scientists, educators, and activists, worked for two years to write the Standards. According to Kim Stoner, Ph.D., the chair of the Committee, “these Standards are just as rigorous as those set for organic agriculture by Connecticut and Massachusetts NOFA chapters, but they have also been adapted to address the special issues and challenges of designing and maintaining landscapes.” The 60-page Standards spell out recommended, allowed, and prohibited practices to conform to organic standards. The Committee developed a 30-hour course to certify land care professionals in organic landscape management. The graduates of this course will make up the NOFA list of accredited organic land care professionals. Programs for the public are being planned for spring 2002 to highlight the benefits of organic land care methods and materials. Also, a survey will soon be underway to identify which garden centers and chain stores in Massachusetts offer organic soil amendments and materials for sale to consumers. The survey results and list of accredited professionals will be included in the upcoming “A Citizen’s Guide to Organic Land Care”. The Organic Land Care Committee’s mission is: education of land care professionals and concerned citizens in the practice of organic land care, with the goals of maintaining soil health, eliminating synthetic pesticide and synthetic fertilize use, increasing landscape diversity, and improving the health and well-being of the people and web of life in our care. Printed copies of the Standards are now available for $20 each from NOFA/Mass, 411 Sheldon Road, Barre, MA 01005; (978) 355-2853; www.massorganic.org. For more information about the Organic Land Care Standards or to be notified of courses and publications, please contact Marilyn Castriotta, Organic Land Care Program Administrator, at (781) 646-6322 or castriotta@aol.com. To subscribe to the gnf, send an e-mail to majordomo@umassextension.org. In the body of the message, type: subscribe gnf. Leave the subject field blank. To unsubscribe, send an e-mail to majordomo@umassextension.org. In the body of the message, type: unsubscribe gnf. Leave the subject field blank. Submitted by Jim Willmott, Camden County Agricultural Agent. ❏ T VOL. 8 NO. 1 Nursery & Greenhouse Film Recycling N ew Jersey’s 2002 nursery and greenhouse film collection and recycle program will be held for the 6th year. This year’s program has been expanded to include collection from out-of-state growers. Participating growers can take film to one of three collection sites (see below). Each film collection site has specific procedures that must be followed when film is transported to the site, as well as it’s own collection dates and tipping fees. Contact the sites to determine the particular procedure that must be followed. For additional information on the nursery & greenhouse film recycling program, growers can contact the New Jersey Nursery & Landscape Association at 609-291-7070 or Karen Kritz at the New Jersey Department of Agriculture at 609-984-2506 or e-mail Karen.Kritz@ag.state.nj.us. The following are the collection sites: Cumberland County Solid Waste Complex Deerfield, NJ 856-825-3700 Contact: Dennis DeMatte, Jr. East Coast Recycling Associates Millville, NJ 856-327-888 Contact: George Glenn III Burlington County Occupational Training Center Mt. Holly, NJ 609-267-6889 ext. 160 Contact: Kevin Carducci or Stephen Paulo COMMERCIAL OPERATOR FROM PAGE 4 licenses can be obtained by contacting the DEP Pesticide Control Program at 609-984-6601 or on the internet at http://www.state.nj.us/dep/ enforcement/pcp/. Once the application is submitted the applicant should undergo the “on-the-job” part of the process. Remember that the supervising commercial pesticide applicator is responsible for keeping and maintaining records of the ”on-the-job” training for each commercial pesticide operator under his/her supervision.❏ PAGE 5 Plant & Pest Advisory 18 College Farm Road Cook College New Brunswick, N.J. 08901-8551 Rutgers Cooperative Extension - NJAES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Rutgers -The State University of New Jersey PLANT & PEST ADVISORY LANDSCAPE NURSERY & TURF EDITION CONTRIBUTORS RCE Specialists and Staff Bruce B. Clarke, Ph.D., Turf Pathology Ann B. Gould, Ph.D., Ornamentals Plant Pathology Steven Hart, Ph.D., Weed Science Joseph R. Heckman, Ph.D., Soil Fertility Albrecht Koppenhofer, Ph.D., Turfgrass Entomology James A. Murphy, Ph.D., Turf Management George J. Wulster, Ph.D., Floriculture Richard J. Buckley, Coordinator, Plant Diagnostic Laboratory RCE County Agricultural Agents and Program Associates Atlantic, Charlene H. Costaris (609-625-0056) Bergen, Joel Flagler (201-599-6162) Burlington, Raymond J. Samulis (609-265-5050) Camden, James Willmott (856-566-2900) Cumberland, James R. Johnson (856-451-2800) Essex, Jan Zienteck, Program Coordinator (973-353-5958) Gloucester, Jerome L. Frecon (856-881-4191) Hunterdon, Winfred P. Cowgill, Jr. (908-788-1338) Mercer, Annette Capp, Program Associate (609-989-6830) Middlesex, William T. Hlubik (732-745-3443) Monmouth, Richard G. Obal (732-431-7261) Morris, Pedro Perdomo (973-285-8307) Ocean, Steven Rettke, Program Associate IPM (732-349-1246) Somerset, Nick Polanin (908-526-6293) Union, Madeline Flahive-DiNardo (908-654-9854) Warren, William H. Tietjen (908-475-6505) Newsletter Production Jack Rabin, Associate Director for Farm Services, NJAES Cindy Rovins, Crop Management Communications Editor Rutgers Cooperative Extension (RCE) provides information and educational services to all people without regard to sex, race, color, national origin, disability, or age. RCE is an Equal Opportunity Employer. Pesticide User Responsibility: Use pesticides safely and follow instructions on labels. The pesticide user is reponsible for proper use, storage and disposal, residues on crops, and damage caused by drift. For specific labels, special local-needs label 24(c) registration, or section 18 exemption, contact RCE in your County. Use of Trade Names: No discrimination or endorsement is intended in the use of trade names in this publication. In some instances a compound may be sold under different trade names and may vary as to label clearances. Reproduction of Articles: RCE invites reproduction of individual articles, source cited with complete article name, author name, followed by Rutgers Cooperative Extension, Plant & Pest Advisory Newsletter. For back issues, visit our web site at: www.rce.rutgers.edu/pubs/plantandpestadvisory