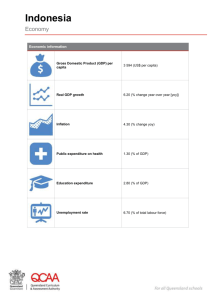

A Case Study: Indonesia’s Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Development

advertisement