Descriptive Statistics Applied Econometrics Michael Ash Econ 753

advertisement

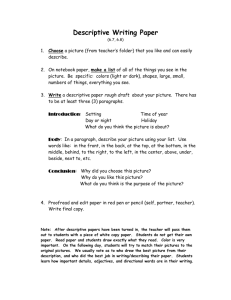

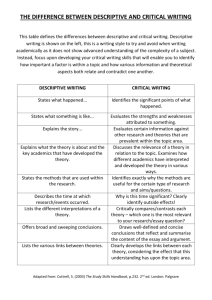

Applied Econometrics Descriptive Statistics Michael Ash Econ 753 Descriptive Statistics – p.1/22 Review of Summers Good econometrics • Interesting Bad econometrics • Exploratory • Critical test of deductive models • Robust • Deep structural parameters • Convincingly causal via natural experiments • Identify regularities for theory to explain Descriptive Statistics – p.2/22 Descriptive Statistics and Quantitative Ease • Conversation starters • Examples ◦ Nurses’ unions and heart-attack mortality ◦ Environmental justice • Good graphical practice (Tufte) Descriptive Statistics – p.3/22 Descriptive Statistics • Descriptive statistics should build a case—more than a pro forma presentation of means • Develop stylized facts by separating the data into categories • Generate a puzzle • Multivariate methods then ◦ Elaborate the initial case by demonstrating robustness; or ◦ Unravel the puzzle in a convincing way. Descriptive Statistics – p.4/22 Graphical Excellence The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (Edward Tufte) Graphical excellence is that which gives to the viewer the greatest number of ideas in the shortest time with the least ink in the smallest space. Descriptive Statistics – p.5/22 Lessons of Tufte: Graphics should • show the data • induce the viewer to think about the substance rather than about methodology, graphic design, the technology of graphic production, or something else. • avoid distorting what the data have to say • present many numbers in a small space • make large data sets coherent • encourage the eye to compare different pieces of data • reveal the data at several levels of detail from a broad overview to the fine structure • serve a reasonably clear purpose: description; exploration, tabulation, or decoration • be closely integrated with statistical and verbal descriptions of a dataset Descriptive Statistics – p.6/22 Some Examples • Cancer maps • Early epidemiology: John Snow and Cholera • HIV–effective time series • Communication before the Challenger accident • Phillips Curve • Oil prices • Detailed tables (Carter v. Reagan) • War and Peace (in one page) Descriptive Statistics – p.7/22 Cancer maps • Cancer incidence by county. • Cancer clusters (Civil Action, New Yorker) • Shortcoming ◦ The visual importance of the county is mapped to its geographic area rather than its population. Descriptive Statistics – p.8/22 Cholera • Dr. John Snow and the London cholera epidemic of 1854 • Maps are effective where where spatial relationship matters, i.e., the proximity of two different places matters: proximity of the Vaux Hall water company pump to the houses with cholera deaths. • On the other hand, if you want to establish within-place association, a scatterplot may be better, e.g., toxic emission rates and race might do better on a scatterplot than on two maps or on one map with two coding systems. See, for example, Ash and Fetter. Descriptive Statistics – p.9/22 HIV and deaths among the young • Easy to see the rise of HIV • Criticisms ◦ Young people die at much lower rates than do old people ◦ Men’s and women’s scales are quite different: young men die at about twice the rate of young women. Descriptive Statistics – p.10/22 Bad Communication & the Challenger Accident • In hindsight, clear relationship between temperature and O-ring failures Descriptive Statistics – p.11/22 (Breakdown of the) Phillips Curve • Consider the time series alternative • Criticisms ◦ Scale of each country is different. Descriptive Statistics – p.12/22 Some practical data aesthetics • Don’t waste data graphics to present trend lines without data; one or two numbers express a trend line perfectly well. • Use scatterplots to imply causal relationships that you will assess with other methods, statistical and textual. • Time series plots express periodicity and develop event studies or structural breaks. With trending data, overlaying two time series can be a way to cheat. Use scatterplots for related variables and label dates, e.g., the Phillips curve. Present real prices (unless the topic is price indexes) See oil prices. • Avoid vertical lines in your tables. Columns of numbers divided by whitespace give plenty of division. Use horizontal lines sparingly. The eye does a good job reading a well-designed table without lines. Table should be rich and detailed. (See Carter v. Reagan.) • Go easy on pie charts; because there are relatively few numbers, their contents can almost always be presented better in a table. • Avoid legends; they’re very distracting. Label series directly on Descriptive Statistics – p.13/22 Categories • Race and Ethnicity ◦ Racial categorization: from 5 (hite, black, Asian/PI, Native, Other) to 63 (white (y/n), black (y/n), Asian (y/n), PI (y/n), Native (y/n), Other (y/n)] ◦ Hispanic (y/n) ◦ What do these categories mean? • Profits, returns to capital, surplus value, managerial compensation, returns to risk • Describing and interpreting unemployment Descriptive Statistics – p.14/22 Unemployment • Why study unemployment? Business cycle, wage-setting (reserve army), spatial mismatch, structural change, skills mismatch, skills decay, poverty, inequality, health effects, gender, race. • “Easy” to partition all adults: E +U + N • Who is counted as unemployed? “Persons are classified as unemployed if they do not have a job, have actively looked for work in the prior 4 weeks, and are currently available for work” Data source: Current Population Survey • Who is not counted as unemployed? ◦ discouraged: ◦ underemployed: part-time workers who would prefer full-time work (even 1 paid hour per week); college-educated workers in “high-school jobs”; contingent workers Descriptive Statistics – p.15/22 Approaches • Purpose? Cyclical, Mismatch, Gender, etc. • U1–U6 alternative measures of labor underutilization (Analogy to M1 , . . . , Mn measure of the money supply) Descriptive Statistics – p.16/22 Alternative measures of labor underutilization U-1 Persons unemployed 15 weeks or longer, as a percent of the civilian labor force (2.3 percent in 2003) U-2 Job losers and persons who completed temporary jobs, as a percent of the civilian labor force (3.3 percent) U-3 Total unemployed, as a percent of the civilian labor force (official unemployment rate) (6.0 percent) U-4 Total unemployed plus discouraged workers, as a percent of the civilian labor force plus discouraged workers (6.3 percent) U-5 Total unemployed, plus discouraged workers, plus all other marginally attached workers, as a percent of the civilian labor force plus all marginally attached workers (7.0 percent) U-6 Total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers, plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of the civilian labor force plus all marginally attached workers (10.1 percent) Descriptive Statistics – p.17/22 Alternative measures of slack • EPOP (employment-to-population ratio) ◦ Source: Current Population Survey ◦ Does not include the intentionality implicit in measures of labor underutilization. ◦ Secular trends, typically segmented by sex • Capacity Utilization (source: Federal Reserve Board survey of businesses) Descriptive Statistics – p.18/22 Current Population Survey • Approximately 50,000 households per month • Partial panel structure (4–8–4) • Monthly Social, demographic, and labor force questions • Supplements: smoking, school enrollment, voting, fertility, training • January 1994 Redesign: (un)employment questions had been asked in an explicitly sexist fashion. If the respondent “appeared to be a homemaker,” the manual instructed interviewers to ask “What were you doing most of last week—keeping house or something else?” . . . For . . . other respondents, interviewers were instructed to ask, “What were you doing most of last week—working or something else?” The redesign affected the measured unemployment rate for women (raising it). It also affected the measurement part-time workers voluntarily and involuntarily so employed. • Representative of the U.S. population, rich questions, regular Descriptive and Statistics – p.19/22 Environmental Justice (Ash and Fetter 2004) • EJ: differential availability of environmental amenities or exposure to environmental disamenities on the basis of socioeconomic, ethnic, or racial differences. • Industrial toxic exposure in the United States • EPA Toxic Release Inventory and neighborhood-level U.S. Census data • Toxic data adjusted for fate and dispersion and toxicity • Key findings ◦ Blacks tend to live both in more polluted cities in the U.S. and in more polluted neighborhoods within cities. ◦ Hispanics live in less polluted cities on average, but they live in more polluted areas within cities. ◦ Strong income-pollution gradient, with lower income people significantly more exposed. Descriptive Statistics – p.20/22 Descriptive statistics, plots, results • Histogram • City halves • Milwaukee maps (dropped in final) • Results At the median, a 10,000 dollar increase in income is associated with a 7 percentage point decrease in the probability of being in the more polluted half of the city. Descriptive Statistics – p.21/22 Nurses Unions and Heart Attack Mortality • Do unionized registered nurses achieve better patient outcomes? ◦ Why plausible (briefly)? ◦ Strategy: compare risk-adjusted heart-attack mortality in union and non-union hospitals in California (early 1990’s) ◦ Strong bivariate relationship (prima facie evidence) ◦ But also substantive differences between union and non-union hospitals ◦ Multivariate and specification test to buttress causal claim. Descriptive Statistics – p.22/22