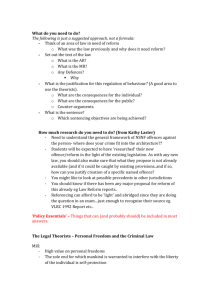

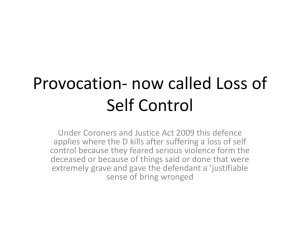

Reforming Criminal Code Defences: Provocation, Self

advertisement