PSYCHOLOGY

(8th Edition)

David Myers

PowerPoint Slides

Aneeq Ahmad

Henderson State University

Worth Publishers, © 2006

1

Perception

Chapter 6

2

Perception

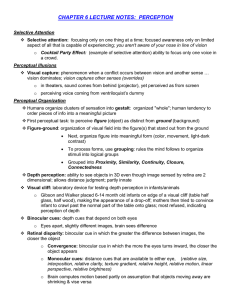

Selective Attention

Perceptual Illusions

Perceptual Organization

Form Perception

Motion Perception

Perceptual Constancy

3

Perception

Perceptual Interpretation

Sensory Deprivation and

Restored Vision

Perceptual Adaptation

Perceptual Set

Perception and Human Factor

4

Perception

Is there Extrasensory

Perception?

Claims of ESP

Premonitions or Pretensions

Putting ESP to Experimental Test

5

Perception

The process of selecting, organizing, and

interpreting sensory information, which

enables us to recognize meaningful objects

and events

(Top down processing).

6

7

Selective Attention

Perceptions about objects change from moment to

moment. We can perceive different forms of the

Necker cube; however, we can only pay attention

to one aspect of the object at a time. Other

examples: the Stroop Task, dichotic listening)

Necker Cube

8

Stroop Task

9

GREEN

YELLOW

BLUE

BLUE

YELLOW

GREEN

BLUE

RED

STROOP TASK

Green

Red

Blue

Purple

Blue

Purple

Blue

Purple

Red

Green

Purple

Green

11

SELECTIVE ATTENTION

• Stress narrows attention

• OTHER EXAMPLES:

– Cell phones in car

–?

12

Count the number of times the

ball is passed:

• http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG6

98U2Mvo

13

Inattentional Blindness

Daniel Simons, University of Illinois

Inattentional blindness refers to the inability to

see an object or a person in our midst. Simmons

& Chabris (1999) showed that half of the

observers failed to see the gorilla-suited

assistant in a ball passing game..

14

Change Blindness

• http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HVw9kWkPX0

15

Change Blindness

Change blindness is a form of inattentional blindness in which

two-thirds of individuals giving directions failed to notice a change

in the individual asking for directions.

© 1998 Psychonomic Society Inc. Image provided courtesy of Daniel J. Simmons.

16

INATTENTIONAL

BLINDNESS

• CHANGE DEAFNESS

• CHOICE BLINDNESS

• CHOICE BLINDNESS BLINDNESS

17

POP-OUT, opposite of

inattentional blindness

• A STRIKINGLY

DISTINCT

STIMULUS

AUTOMATICALLY

DRAWS OUR EYE:

accomplished by

parallel processing

18

ATTENTION

•

•

•

•

•

Attentional resources are limited

Attention can be divided

Attention requires effort.

Attention improves mental processing

Control of attention can be voluntary or

involuntary

19

ATTENTION

• Overt vs covert orienting

– Overt: pointing sensory systems at a

particular stimulus Example?

– Covert: Shifting attention without the

appearance of shifting the sensory system

Example?

20

Perceptual Illusions

Illusions provide good examples in

understanding how perception is organized.

Studying faulty perception is as important as

studying other perceptual phenomena. MullerLyer Illusion:

Line AB is longer than line BC.

21

Tall Arch

Rick Friedman/ Black Star

In this picture, the

vertical dimension

of the arch looks

longer than the

horizontal

dimension.

However, both are

equal.

22

Illusion of a Worm

© 1981, by permission of Christoph Redies and

Lothar Spillmann and Pion Limited, London

The figure on the right gives the illusion of a blue hazy

“worm” when it is nothing else but blue lines identical

to the figure on the left.

23

Reprinted with kind permission of Elsevier Science-NL. Adapted from

Hoffman, D. & Richards, W. Parts of recognition. Cognition, 63, 29-78

3-D Illusion

It takes a great deal of effort to perceive this figure in

two dimensions.

24

Reprinted with kind permission of Elsevier Science-NL. Adapted from

Hoffman, D. & Richards, W. Parts of recognition. Cognition, 63, 29-78

3-D Illusion

It takes a great deal of effort to perceive this figure in

two dimensions.

25

Sidewalk Art

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKJ0KY

nB5R8

26

Perceptual Organization

When vision competes with our other senses,

vision usually wins – a phenomena called visual

capture.

How do we form meaningful perceptions from

sensory information? We organize it.

Gestalt psychologists showed that a figure

formed a “whole” different than its surroundings:

”the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”.

27

PERCEPTUAL

ORGANIZATION

• Sensation (bottom up processing) and

Perception (top down processing) blend into

one continuous process

• Fundamental point: We constantly filter

sensory information and infer perceptions in

ways that make sense to us. Mind matters.

28

Form Perception

Organization of the visual field into objects

(figures) that stand out from their surroundings

(ground). Another example: cocktail party

phenomena

Time Savings Suggestion, © 2003 Roger Sheperd.

29

30

31

32

REVERSIBLE FIGURE

GROUND

• Reversible figureground illusions

demonstrate that the

same stimulus can

trigger more than

one perception.

33

REVERSIBLE FIGURE

GROUND

• Reversible figureground illusions

demonstrate that the

same stimulus can

trigger more than

one perception.

34

Grouping

After distinguishing the figure from the ground,

our perception needs to organize the figure into

a meaningful form using grouping rules.

35

GESTALT GROUPING

PRINCIPLES

graphicdesign.spokanefalls.edu/tutorials/p

rocess/gestaltprinciples/gestaltprinc.htm

36

GROUPING

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

_____1. Sometimes interviewers focus on one trait to the

exclusion of others; this one trait, good or bad, is dominant

against the background of other traits.

_____2. “The purpose of this interview, “ Sarah was told, “is

to gather bits and pieces of information about you so that I

might form an overall, meaningful ‘picture’ of you.”

_____3. Sometimes applicants are compared to other

applicants who are the same age, gender, race, education, and so on.

Interviewers have to avoid this tendency because it prevents their

seeing the person as an individual.

_____4. John sees the whole interview process as one, long continuous

stream of asking questions and gathering information.

_____5. Mrs. Thatcher tends to group interviewees together into her

morning” applicants, afternoon” applicants, and “drop-in’s”,

depending on who comes in with whom during the course of a

day’s appointments.

A. gestalt

B. similarity

C. proximity

D. continuity

E figure-ground

37

Grouping & Reality

Although grouping principles usually help us

construct reality, they may occasionally lead us

astray.

Both photos by Walter Wick. Reprinted from GAMES

Magazine. .© 1983 PCS Games Limited Partnership

38

OTHER GROUPING

PRINCIPLES

• LIKLIHOOD PRINCIPLE: we tend to

perceive objects in the way that

experience tells us is the most likely

physical arrangement

• Auditory scene analysis

– Sound localization

– Visual capture

39

Depth Perception

Innervisions

Depth perception enables us to judge distances.

Gibson and Walk (1960) suggested that human

infants (crawling age) have depth perception.

Depth perception appears to be innate, amplified by

experience

Visual Cliff

40

DEPTH PERCEPTION

• Two dimensional images fall on our retina,

how do we see three dimensionally?

• Depth perception (seeing objects in three

dimensions) allows us to judge distance

41

RETINAL DISPARITY

• Note on the diagram how each eye

sees the object from a different angle

• Retinal disparity = binocular disparity

42

Binocular Cues

Retinal disparity: Images from the two eyes differ. Brain

compares these images, their differences provide cues to relative

distance of different objects Try looking at your two index

fingers when pointing them towards each other half an

inch apart and about 5 inches directly in front of your eyes.

You will see a “finger sausage” as shown in the inset.

43

Binocular Cues

Convergence: Neuromuscular cues. When two eyes

move inward (towards the nose) to see near objects and

outward (away from the nose) to see faraway objects.

Accomodation – muscles surrounding the lens

tightening

44

45

BINOCULUAR CUES

• Hole in the Hand – roll a sheet of paper into a

tube and raise it to your right eye like a

telescope.

• Look through it, focusing on a blank wall in

front of you. Hold open left hand beside the

tube and continue to focus ahead

• The images received by the two eyes will fuse

and the hole in the tube will appear to be in

your hand!

46

Monocular Cues

Relative Size: If two objects are similar in size,

we perceive the one that casts a smaller retinal

image to be farther away.

47

Monocular Cues

Interposition: Objects that occlude (block) other

objects tend to be perceived as closer.

Rene Magritte, The Blank Signature, oil on canvas,

National Gallery of Art, Washington. Collection of

Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon. Photo by Richard Carafelli.

48

Monocular Cues

Relative Clarity: Because light from distant objects

passes through more light than closer objects, we

perceive hazy objects to be farther away than

those objects that appear sharp and clear.

49

Monocular Cues

Texture Gradient: Indistinct (fine) texture

signals an increasing distance.

© Eric Lessing/ Art Resource, NY

50

Monocular Cues

Relative Height: We perceive objects that are higher in our

field of vision to be farther away than those that are lower.

Image courtesy of Shaun P. Vecera, Ph. D.,

adapted from stimuli that appered in Vecrera et al., 2002

51

Monocular Cues

Relative motion: Objects closer to a fixation point move

faster and in opposing direction to those objects that

are farther away from a fixation point, moving slower

and in the same direction.

52

Monocular Cues

Linear Perspective: Parallel lines, such as

railroad tracks, appear to converge in the

distance. The more the lines converge, the

greater their perceived distance.

© The New Yorker Collection, 2002, Jack Ziegler

from cartoonbank.com. All rights reserved.

53

Monocular Cues

Light and Shadow: Nearby objects reflect more light

into our eyes than more distant objects. Given two

identical objects, the dimmer one appears to be farther

away.

From “Perceiving Shape From Shading” by Vilayaur

S. Ramachandran. © 1988 by Scientific American, Inc.

All rights reserved.

54

Motion Perception

Motion Perception: Objects traveling towards us

grow in size (looming) and those moving away

shrink in size. The same is true when the observer

moves to or from an object. Evolutionary importance

of detecting movement: wiggle your finger demo

55

Apparent Motion

Phi Phenomenon: When lights flash at a certain

speed they tend to present illusions of motion.

Neon signs use this principle to create motion

perception.

Two lights

one

after the Illusion

other. of motion.

One light jumping

from flashing

one point

to another:

56

Perceptual Constancy

Perceiving objects as unchanging even as

illumination and retinal images change. Brain needs

to recognize the object without being deceived by

changes. Perceptual constancies include

constancies of shape and size.

Shape Constancy

57

Perceptual Constancy

• Hold a hand in front of you at arm’s length and move

it toward your head, then away; there will be no

perceived change in size. However, retinal image

size is changing. How can we detect?

• Hold forefinger of left hand about 8 inches in front of

your face and focus on it

• Now position your right hand at arm’s length past

your left forefinger.

• While maintaining fixation on left fingertip, move your

right hand toward and away from your face.’

• Focus on finger, but also notice image of the hand as

it moves. It will change dramatically in size

58

Size Constancy

Stable size perception amid changing size of the

stimuli.

Size Constancy

59

Size-Distance Relationship

The distant monster (below, left) and the top red bar

(below, right) appear bigger because of distance cues.

Cultural experience also influences.

Alan Choisnet/ The Image Bank

From Shepard, 1990

60

Size-Distance Relationship

Both girls in the room are of similar height.

However, we perceive them to be of different

heights as they stand in the two corners of the

room.

Both photos from S. Schwartzenberg/ The Exploratorium

61

Ames Room

The Ames room is designed to demonstrate the size- 62

distance illusion.

Lightness Constancy

The color and brightness of square A and B are the

same. Depends on relative luminance - the amount of 63

light an object reflects relative to its surroundings.

Color Constancy

Perceiving familiar objects as having consistent

color even when changing illumination filters

the light reflected by the object.

Color Constancy

64

COLOR CONSTANCY

• http://www.cnn.com/2009/OPINION/10/

26/lotto.optical.illusions/index.html

65

Perceptual Interpretation

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) maintained that

knowledge comes from our inborn ways of

organizing sensory experiences.

John Locke (1632-1704) argued that we learn to

perceive the world through our experiences.

How important is experience in shaping our

perceptual interpretation?

66

Restored Vision

After cataract surgery,

blind adults were able to

regain sight. These

individuals could

differentiate figure and

ground relationships, yet

they had difficulty

distinguishing a circle

and a triangle. (Von

Senden, 1932).

67

Facial Recognition

Courtesy of Richard LeGrand

After blind adults

regained sight, they were

able to recognize distinct

features, but were unable

to recognize faces.

Normal observers also

show difficulty in facial

recognition when the

lower half of the pictures

are changed.

68

Sensory Deprivation

Kittens raised without

exposure to horizontal

lines later had difficulty

perceiving horizontal

bars. Influence of

critical periods shown.

Blakemore & Cooper (1970)

69

Perceptual Adaptation

Courtesy of Hubert Dolezal

Visual ability to adjust to

an artificially displaced

visual field, e.g., prism

glasses. Stratton

experiment with optical

headgear.

70

PECEPTUAL ADAPTATION

• Form groups of four or five.

• Pick up a set of goggles and a ball.

• Assign roles: catcher, pitcher, subject

(rotate roles)

71

72

Problems with Schemas

(Allport & Postman, 1947)

73

Allport and Postman

• LEVELING - perceiver drops certain

details because they don’t “fit”

• SHARPENING - details consistent with

values and interests are emphasized

• ASSIMILATION - padding and

organization used to make central

theme fit subject’s expectations

74

Perceptual Set

A mental predisposition to perceive one thing

and not another. What you see in the center

picture is influenced by flanking pictures.

Whisper Down the Lane example.

From Shepard, 1990.

75

PERCEPTUAL SET

• Our Whisper Down the Lane example

was based on Allport and Postman’s

1945 study

• Story was altered to fit the social

expectations and stereotypes of the

subjects.

• Three major perceptual distortions in

transmission of information:

76

77

Perceptual Set

Other examples of perceptual set.

Dick Ruhl

Frank Searle, photo Adams/ Corbis-Sygma

(a) Loch ness monster or a tree trunk;

(b) Flying saucers or clouds?

78

Other Examples of Perceptual

Set

• Provide punctuation that will make the

words meaningful:

• “TIME FLIES I CANT THEYRE TOO

FAST!”

79

EXPLANATION

• Apostrophes come easily, but the rest is

difficult.

• We’re too familiar with the slogan.

• Think of time as a verb rather than a

noun. Now it makes sense!

80

PERCEPTUAL SET

What determines perceptual set?

• Through experience we form concepts, or

schemas, that organize and interpret unfamiliar

information.

– Example: a child’s simplified drawing of people

• Our innate schemas for faces primes us, especially

attune to the eyes and mouth

81

Schemas

Schemas are concepts that organize and

interpret unfamiliar information.

Courtesy of Anna Elizabeth Voskuil

Children's schemas represent reality as well as their

abilities to represent what they see.

82

Features on a Face

Face schemas are accentuated by specific

features on the face.

Kieran Lee/ FaceLab, Department of Psychology,

University of Western Australia

Students recognized a caricature of Arnold

Schwarzenegger faster than his actual photo.

83

Eye & Mouth

Eyes and mouth play a dominant role in face

recognition.

Courtesy of Christopher Tyler

84

Context Effects

Context can radically alter perception.

Is the “magician cabinet” on the floor or hanging from the

ceiling?

85

Cultural Context

Context instilled by culture also alters

perception.

To an East African, the woman sitting is balancing a metal

box on her head, while the family is sitting under a tree.

86

Perception Revisited

Is perception innate or acquired?

87

Perception & Human Factors

Human Factor Psychologists design machines

that assist our natural perceptions.

Courtesy of General Electric

Photodisc/ Punchstock

The knobs for the stove burners on the right are easier to

understand than those on the left.

88

Human Factors &

Misperceptions

Understanding human factors enables us to

design equipment to prevent disasters.

Two-thirds of airline crashes caused by human error are

largely due to errors of perception.

89

Human Factors in Space

To combat conditions of monotony, stress, and

weightlessness when traveling to Mars, NASA engages

Human Factor Psychologists.

Transit Habituation (Transhab), NASA

90

HUMAN FACTORS

PSYCHOLOGY

• Examples of poor design?

• Why do experts often come up with poor

solutions?

“Curse of knowledge” – the mistaken

assumption that others share our expertise and will

behave as we would

Fail to schedule user-testing to reveal

perception-based problems prior to production and

distribution

91

Is There Extrasensory

Perception?

Perception without sensory input is called extrasensory

perception (ESP). A large percentage of scientists do

not believe in ESP.

PARAPSYCHOLOGY: THE STUDY OF

PARANORMAL PHENOMENON.

92

Claims of ESP

Paranormal phenomena include astrological

predictions, psychic healing, communication with

the dead, and out-of-body experiences, but most

relevant are telepathy, clairvoyance, and

precognition.

93

Claims of ESP

1.

Telepathy: Mind-to-mind communication.

One person sending thoughts and the other

receiving them.

2. Clairvoyance: Perception of remote events,

such as sensing a friend’s house on fire.

3. Precognition: Perceiving future events,

such as a political leader’s death.

94

Premonitions or Pretensions?

Can psychics see the future? Can psychics aid

police in identifying locations of dead bodies?

What about psychic predictions of the famous

Nostradamus?

The answers to these questions are NO!

Nostradamus’ predictions are “retrofitted” to

events that took place after his predictions.

95

Putting ESP to Experimental Test

In an experiment with 28,000 individuals,

Wiseman attempted to prove whether or not

one can psychically influence or predict a coin

toss. People were able to correctly influence or

predict a coin toss 49.8% of the time.

96

ESP CLAIMS

• To give ESP credibility, you would need:

A reproducible phenomenon and a theory to

explain it

97

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

Representative

Sample (larger

Apply methods of

control

Apply Methods of

control

Population

the better)

Experimental

Group

Independent

Variable

Measure

Dependent

Variable

Random

Assignment

Control

Group

=

Placebo

Is the difference

statistically

significant?

Measure

Dependent

Variable

98

PERCEPTION EXPERIMENT

• Step One: Brainstorm ideas for an

experiment.

• Remember: develop an idea based on a

perceptual concept.

• Develop a hypothesis, with an independent

variable and dependent variable. A good

format for hypothesis: If ________, then

_____.

• Operationally define variables.

99

INTRODUCTION – Why Am I

Doing This Study?

• You will need to research your topic for the

Introduction (review of past research, justify

the logic of the study, and presenting your

hypothesis)

• Check your textbook for background

information. You need to cite two additional

sources in your Introduction.

• Introduction: two pages; last sentence should

be the hypothesis, with iv,dv, op def

100

METHOD – What Did I Do?

• Based on your description of the

apparatus and procedures could

someone replicate your experiment?

• Have separate sections labeled:

Subjects (include description of

population and method of selection),

Procedures (you may number this),

Materials and Apparatus

101

CONSENT FORM

• ..\AP Notes\Perception\Consent Form

for Experiment.doc

102

RESULTS – What Did I Find?

• Graphs, charts, tables that present an

analysis of your findings.

• You do NOT interpret the results in this

section.

• You do not present the raw data here,

but you should include it in an Appendix

if required.

103

DISCUSSION - What is the

Significance of My Findings?

• You relate your findings to your hypothesis

and the theories you investigated. Did you

support your hypothesis? A null hypothesis is

one where no effect is expected.

• You may need to explain why you did not get

the results you expected. Were there

confounding variables, experimenter bias,

etc.?

• Identify new or additional questions raised by

your study.

104

REFERENCES – How Do I Give

Credit Where Credit Is Due?

• Requirement: two sources in addition to

textbook

• You need to use the APA style for your

citations and reference page

• Place appropriate citations in the paper

as well as including a reference page.

• It is better to overcite than to undercite.

105

APA STYLE

• CITATION EXAMPLES:

– the effects of unchecked infections

accumulate (Neese, 1991)

– Carrie Armel and Vilayanur Ramachandran

(2003) cleverly illustrated….

106

APA STYLE

•

Reference Page Examples:

Journal:

Murzynski, J. (1996). Body language of women. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, 26, 1617 – 1626.

Book:

Paloutzian, R. F. (1996). Invitation to the psychology of religion. (2nd ed.).

Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Online:

Nielsen, M.E. Notable people in psychology. Retrieved August 3, 2005,

from http://www. psywww.com

Encyclopedia

Shea, J.D. (2004) Depression and Adjustment. In J.F. Schumaker (Ed),

Encyclopedia of Mental Health (pp. 70-84). New York: Oxford /University

Press.

107

APPENDIX

• If necessary, this might include:

– Copies of surveys, pictures, etc used as

materials

– Raw data

108