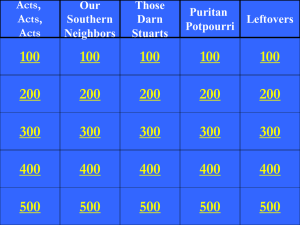

NEW Unit 3 - Crisis of State 1642-1689

advertisement