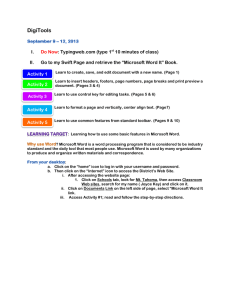

Assessing Monopoly Power in Dominance Cases

advertisement

Assessing Monopoly Power in Abuse of Dominance Cases Eric Emch, OECD eric.emch@oecd.org 1 Overview of Talk I. Definitions II. Structural evidence of monopoly power III. Direct evidence of monopoly power IV. Final thoughts 2 Definitions • Market power: Roughly, ability to price above shortrun cost in some market, often limited to marginal cost. Most firms have some market power, for instance due to product differentiation or temporary first-mover advantages. • Monopoly power: “Substantial and durable” market power. Ability to price substantially above economic cost for an extended period of time. Usually implies some form of entry barrier, else entry would limit durability of supracompetitive pricing. 3 Definitions (2) • Dominance: Some jurisdictions, including the EU, have looked to the following definition from the EC courts: • “ a position of economic strength enjoyed by an undertaking which enables it to prevent effective competition being maintained on the relevant market by affording it the power to behave to an appreciable extent independently of its competitors, its customers, and ultimately of the consumers.” – Case 27/76 United Brands v. Commission [1978] • But this definition is confusing to an economist. For instance, What does it mean exactly to act independently of customers? Even a monopolist must price according to a demand curve, which is defined by customer preferences. Constraints on a firm are a matter of degree, rather than a simple 0-1 of “independent” or not. 4 Definitions (3) • Authorities in the EU and elsewhere have noted difficulties with the definition of “dominance” given by United Brands case – Has been interpreted by some observers as simply meaning that competitive constraints are weak. • In practice, dominance is often defined similarly to monopoly power, and both share the following characteristics – Weak competitive constraints/ability to price significantly above cost – Durable position • In what follows, I will treat dominance and substantial market power as equivalent. • Note that all of these definitions are in reference to a particular market, not a firm. A firm may have market power in some markets but not others. 5 Q: What Is The Offense? (A: Not dominance alone) • “Competition policy is not concerned with monopolies per se, but only with monopolies that distort the competitive process,” Motta, Competition Policy: Theory and Practice – In abuse of dominance cases, one takes the existence of the monopoly power as given. That is not the offense, except perhaps if one is trying to break up a previous illegal merger – Assessing market power, the subject of this talk, is only step one of the process. Assessing the competitive effects of disputed actions may be the more difficult part. That is the subject of the rest of this seminar. • I will focus on unilateral, as opposed to collective, dominance. It is generally easier to prove a case if there is an element of horizontal coordination. 6 Structural vs. Direct Evidence • Structural Evidence: Assessing objective, structural characteristics of the market that provide indirect evidence of dominance. • Direct Evidence: Looking more directly at measures of market power relating to price or profit of a firm, or anticompetitive effects of its actions • In practice, competition authorities assess all structural and direct evidence of market power. Structural measures may be important for legal presumptions. Economically, probably the most important single factor is barriers to entry/expansion for competitors. 7 STRUCTURAL EVIDENCE OF DOMINANCE 8 Possible Structural Indicators 1. High market share (as a proxy for lack of competitive constraints within the market) – Problems: difficult to delineate market; must be clear on what market shares actually mean; better to look directly at constraints than to focus too much on share 2. Barriers to entry/expansion (a lack of competitive constraints outside the market) – Problems: important to understand structural source of barrier; if “barrier” is a result of strategic actions, need to understand the underlying source of market power that makes strategic barrier possible 3. Lack of buyer power (lack of competitive discipline from the buyer side) 9 Defining a Market • To calculate market share, one first needs to delineate a market. The most common paradigm is the hypothetical monopolist test, designed for merger cases. – HMT: Start with the product of interest and combine it with its closest substitute. Would a monopolist of these products be able to institute a Small but Significant and Nontransitory Increase in Price (SSNIP)? If no, keep adding substitutes until answer is yes. At the stopping point, you have a market. • In merger cases, to calculate the SSNIP, compare the hypothetical monopolist price to the prevailing price. • In dominance cases what is the relevant price comparison? Prevailing price may already reflect substantial market power. 10 The “Cellophane Fallacy” • Term from U.S. v. E.I. de Pont de Nemours & Co (1956). In that case, the court examined whether duPont had market power in the pricing of cellophane, a plastic wrap. The court determined that duPont lacked market power because at current market prices a user of cellophane had many substitutes and cellophane was therefore in a market with all wrapping materials. • The error: The reason for the seemingly close substitution was that cellophane was marked up substantially over cost to the point where further price increases were constrained by substitutes. • This raises a more general point: If a firm is already exercising substantial market power, considering a further hypothetical 5-10% price rise over the current price by the firm at issues seems nonsensical as a method for assessing its market power. • What to do? 11 Market Def. in Dominance Cases • Calculate price increase from the “competitive price”? – Very difficult to estimate first, a competitive price, then, demand at that price (which may be far away from current price), and also demand at a 5-10% rise from competitive price. – Also, if you are confident about the competitive price, why not just measure the current price relative to the competitive price to directly measure market power, rather than going through the market definition exercise? • Calculate effect of a 5-10% price decrease? – May give a quick estimate of close substitutes at current prices that would be purged at a somewhat lower price. – But if prevailing price is much higher than competitive price, not clear what this is telling us. 12 Bottom Line • Market definition is an imperfect exercise in any case, but in abuse of dominance cases it is especially difficult (though if the case involves “leverage” of power into a new market, may be easier to use traditional market definition methods in the leveraged market) • In practice, market definition in abuse of dominance cases that go to court is often done not so mechanistically but by a combination of SSNIP-like exercises, qualitative evidence about close substitutes, and market participants views of the market. Each has its flaws. • EU Article 82 discussion paper recommends using a variety of methods to test robustness of market definition, including, e.g., looking directly at potential substitutes, comparing prices across regions, and trying a SSNIP test based on “competitive price.” 13 Market Shares • We’ve discussed how imperfect the market definition exercise can be; we thus should be wary of placing too much faith in market shares alone. • Even assuming correct market definition, calculating market shares raises more difficult issues, for instance: – Which units do we use: Capacity? Revenue? Physical units? – What does market share mean in a particular market? – Is the market share durable? 14 Why Do We Care About Share At All? • Measure of competition within the market – A proxy for lack of competitive constraints from existing competitors, implying difficulty of expansion • Customer switching costs? • Supply side or demand side economies of scale? • Perhaps a measure of difficulty of entry as well? • Important: Shouldn’t focus exclusively on share. Look directly at competitive constraints on a firm. 15 Market Share: Units • Some possibilities: – Units of output. But need to find common denominator. May be easier in some cases (e.g., loaves of bread) than others (heat content of coal, sweetening power of artificial sweeteners) – Revenues. But price differences will reflect quality differences, and not clear that high quality should mean higher share. – Capacity. Not always appropriate, but may be in markets where capacity limitations define long-term production, even if year-to-year output varies. – Resources, reserves, IP: If the critical components of competition are access to critical inputs, perhaps should focus on access to that critical input, like coal reserves or particular IP rights. • Appropriate measure will vary by market; authorities will often calculate market share in several different ways to test robustness. 16 Market Shares in Bid Markets (“1/n markets”) • If the market is characterized by discrete, repeated rounds of bidding, for example military procurement contracts, not clear what market share between rounds of bidding means for the next bid. • For instance, if bid round #1 for helicopter engines from three firms results in firm 1 winning the contract as the primary contractor and firm 2 as the second source, market shares may be 80/20/0 for the next few years. • But when the next bid comes around, will this bid look like a very skewed duopoly or a health competition between three roughly equal firms? • Shares alone won’t tell us. Need to assess the assets required to be effective competitors. If all three will be effective competitors the next time around, may consider this a “1/n” market, where each of n competitors is roughly equal in terms of their market strength. 17 Market Shares: Legal Presumptions • Various competition authorities set different market share thresholds for either a presumption of dominance or no dominance. – Presumption established in EU AKZO case according to which 50% market share over time would usually be sufficient to establish dominance. In recent years, however the Commission has not relied as much on this presumption. – No strict market share presumptions for monopoly power in the United States. • Most jurisdictions emphasize the importance of looking at factors beyond market share, though market share can serve as a useful initial screen for dominance. 18 Barriers to Entry/Expansion • A very central issue, all would agree. Necessary but not a sufficient condition for concern. – High shares with low entry barriers: probably no abuse of dominance problem that will not be solved with entry. – Low shares with high entry barriers: could be a problem, depending on extent of existing competition. • Some assessments of the issue: – Australian High Court: “A large market share may well be evidence of market power … but the ease with which competitors would be able to enter the market must also be considered. It is only when for some reason it is not rational or possible for new entrants to participate in the market that a firm can have market power… There must be barriers to entry. (See Boral v. ACCC) – Canadian Abuse of Dominance Guidelines: “… market share is in itself not sufficient to prove market power. Without barriers to entry, any attempt by a firm with high market shares to exercise market power is likely to be met with entry or expansion by existing firms such that the firm with the high market share loses enough customers to its rivals that it is not profitable to attempt to raise prices above competitive levels.” 19 Entry Barriers (2) • How does one define entry barriers? – Several different definitions have been advanced over the years, but none is ideal, and there is no consensus “correct definition.” • (Stigler): Costs borne by entrants but not by incumbents • (Fisher): Anything that prevents entry when entry would be socially beneficial • “Any feature of a market that places an efficient competitive entrant at a significant disadvantage compared with incumbent firms.” (Aust. MG) • For the purpose of competition enforcers, an entry barrier might be seen as any factor that prevents firms from outside the market from defeating an exercise of market power inside the market. – Whether or not the cost was incurred by the incumbent might be important, separately, for determining whether we are unwisely interfering with dynamic incentives. Should be some benefits to being first to market, else no one will innovate. – Entry barriers not bad in themselves, only to the extent they shield anticompetitive conduct 20 Entry Barriers (3) • Not comprehensive, but the kinds of structural factors that have been identified by competition authorities as entry barriers: • • • • • • • • Sunk costs Regulatory barriers Network effects Customer loyalty and reputation effects Economies of scale and scope Barriers to exit Vertical integration High capital costs 21 Buyer power • What do competition authorities mean by buyer power? Two main answers: 1. Buyers can easily turn to alternatives (essentially, that they have elastic demand in some sense) 2. Buyers are themselves potential entrants or able to sponsor entry. Note that buyer’s size does not necessarily matter when assessing buyer power. Large buyers might have no alternatives, small ones might have many. 22 Structural Factors in Microsoft • EC re: Microsoft dominance in client operating system (from 2004 decision), structural factors – “Microsoft’s dominance relies on very high market shares and significant barriers to entry.” (para. 429) • “Very large market shares, of over 50%, are considered in themselves, and but for exceptional circumstances, evidence of a dominant position. Market shares between 70% and 80% have been held to warrant such a presumption of dominance. Microsoft, with its market shares of over 90%, occupies almost the whole market – it …can be said to hold an overwhelmingly dominant position.” • “Microsoft has held very high market shares in the client PC operating system market for many years.” • Entry barriers derive from network effects/ “applications barrier to entry.” – Lack of buyer power: “Windows appears as a must-carry product for a client PC vendor,” give example of IBM not being able to forego windows even though it made its own PC OS. (para. 462) 23 Structural Factors in Microsoft (2) • EC re: Microsoft dominance in “work group server operating systems” (from 2004 decision), structural factors – High market share • For revenue, software is often bundled with hardware, hard to separate revenues. EC decides to calculate market shares both by combining hardware and software revenues and by calculating units shipped. • Two measures are similar in IDC data: 61% share for Windows in 2002 revenue, 64.9% in units. Netware 8.5/9.4, Linux 10.4/13, UNIX 18.6/11.1. • Conclusion: Microsoft market share at least 60%, Netware 10-25%, Linux 5-15%, UNIX 5-15%. – Barriers to entry/expansion • • • • Applications barrier, but less than in client side Customer familiarity/training with provides positive-feedback loop “Established record,” “proven technology” important to buyers Microsoft control of interoperability information re: client PCs 24 Structural Factors in Microsoft (3) • US Microsoft decision (1999). Court’s assessment of market power in PC OS – High, stable market share: Microsoft’s share of the market is large and stable. For the last decade, every year the Microsoft’s share has stood above 90%, the last couple of years getting to 95%, and projections are that it will be higher. – Barriers to entry/expansion: • “Applications barrier to entry” for new operating systems • Economies of scale in applications development means that developers don’t support smaller operating systems. Indirect network effects in operating systems means that users tend to gravitate toward the operating system with the larger applications base. – Lack of buyer power: Absence of realistic alternatives for computer manufacturers. 25 DIRECT EVIDENCE OF DOMINANCE 26 Direct Evidence of Dominance • Low firm-level demand elasticity – But may require a lot of data to calculate • “High prices” relative to cost – Central to most economic definitions of market power, but as a practical matter what cost measure do we use? What about dynamic considerations? • Profitability of firm or industry – But what constitutes “excess” profits? How do we calculate profits in a particular market from general accounting statements? • Evidence of anticompetitive conduct – Ability to impact competition significantly = market power? – But what are exact criteria? Is this reasoning circular? In theory, these are all useful indicators, but may be more difficult to implement in practice than structural indicators. 27 Assessing Demand Elasticities • A demand elasticity is a measure of the responsiveness of quantity demanded to price. A firm’s own-price elasticity is approximately (∆Q/Q)÷(∆p/p) That is, the percentage change in quantity divided by the percentage change in price • With enough data, one could plot a demand curve and directly estimate cost and markup for a firm, and thus market power, based on current price. In practice, often don’t have enough data. Ask economists for help. 28 Assessing Price Levels • When is price high enough to indicate market power? If one does have cost evidence, one could directly compare a firm’s price to cost. This directly addresses the economic definition of market power. • Problem: very difficult to get good cost data. Accounting data may not measure true economic cost well. Even with good data, it’s not clear which concept of cost is the best to use. • Alternatively, if there are other geographic markets that could serve as a control group, could compare price levels to comparable markets where no market power is being exercised. • A snapshot of prices does not indicate much about levels of market power, need to assess price levels over time. 29 Assessing Profitability • Another way of directly assessing the exercise of substantial market power is to look at a firm’s profits. Must use caution here because there are a number of pitfalls. • First of all, we’re looking at market power in a market, not for the firm as a whole, so need to separate profit data by product line according to antitrust markets; can be difficult with data available. • Secondly, accounting profits and economic profits are not equivalent. For instance, economic profits might be higher than accounting profits if a firm with little competition awards managers high salaries, nice offices, etc. Accounting profits may be higher than economic profits if they don’t include a cost of capital or opportunity costs of resources consumed. • In addition, there are dynamic issues to consider. Profits at a snapshot in time don’t mean much. High profits now may be a result of investments in a previous period, and may look high even if, over an extended period of time, the firm is only returning a normal return on its earlier investment. 30 Assessing Profitability (2) • Other dynamic issues to consider: any risky investment will earn above normal profits in some states of the world. Even if, risk-adjusted, the firm earned a normal return, it may look to be earning above-normal profits if its bet paid off. This indicates good foresight, possibly, but not ex ante market power. • All of this is to say that any evidence related to profitability must be used with caution. There is the possibility of both false positives and false negatives: high reported profits that actually do not indicate market power or low reported profits that mask actual market power. 31 Assessing Anticompetitive Conduct • In certain cases, the conduct of a firm and its competitive effects may also be used as evidence that a firm has substantial market power. • Some have argued that that the focus should be on conduct and competitive effects in abuse of dominance cases; if substantial anticompetitive effects can be shown, then an initial separate inquiry into whether a firm has substantial market power should not be required. 32 Assessing Anticompetitive Conduct (2) • Where conduct is used as evidence of monopoly power, it is necessary to evaluate this evidence as part of a broader story about competitive harm. • It is tempting to say that if a firm can “force” customers or competitors to do something via the “bad act,” then it must have market power. This assumes the answer, however. It may be that the behaviour itself, though it appears to raise price, is either efficient or competitively neutral. Most seemingly exclusionary conduct has an alternative pro-competitive explanation that must be explored. • “One expects a price increase as a result of the alleged bad act if the alleged bad act harms competition, but one could also expect a price increase even when the alleged bad act does not harm competition but improves product quality. Therefore, looking only at the behaviour or price before and after the alleged bad act does not answer whether the bad act really is harmful.” - Dennis Carlton, “Market Definition: Use and Abuse,” Competition Policy International Spring 2007, Vol. 1 No. 3. • 33 Direct Factors in Microsoft • EC re: Microsoft Dominance in client OS (from 2004 decision), direct factors – “Microsoft’s financial performance is consistent with its near-monopoly position in the client PC operating system market.” Cites 81% profit margin for client OS software – Linux is free, “no significant difference in ease of use,” yet has not impacted Microsoft’s financial performance. – IBM, though it has its own operating system, is “obliged to offer its own PCs equipped with the operating system of its direct competitor.” • Note: be careful with simply giving a laundry list of seemingly damning facts. Linux on the desktop even three years later has been recently reviewed by WSJ as not easy enough for most users, and IBM deciding that it was in its interest to offer multiple operating systems on its computers is consistent with dominance or not. These two factors were listed to address the “behaving independently” part of the dominance proof in EU law. 34 Direct Factors in Microsoft (2) • From US Decision, re: Microsoft Monopoly Power in operating systems • Microsoft’s pricing behavior proves its monopoly power – Microsoft did not consider the prices of other vendors’ Intel-compatible PC operating systems when setting the price of Windows 98 – It raised the price it charged OEMs for Windows 95 to the same level it charged for Windows 98 just prior to releasing the newer product. This is contrary to the conduct in a competitive market were an older product’s price should either stay the same or decrease. It can be deduced that Microsoft would not have imposed this price increase if it were concerned that OEM’s might shift their business to another vendor of operating systems or hasten the development of alternatives to Windows. – Microsoft felt it had substantial discretion in setting the price of its Windows 98. • The fact the Windows invests a lot in R&D does not evidence a lack of monopoly power: Windows has an incentive to innovate in Windows as innovations can make Intel-compatible PC systems attractive to more consumers, and those consumers less sensitive to the price of Windows. Even monopolists have incentives to innovate. 35 To Summarize • Assess all potential sources of evidence for monopoly power. There is not a rigid formula for weighing these, but of the factors discussed, understanding the strength and durability of entry barriers is probably the most important • Market shares are only the beginning of the analysis, and should not be considered dispositive • Market power evidence and competitive effects evidence are intertwined. While market power analysis generally should not be skipped entirely, it should be integrated with the rest of the case. 36 Some References • • • • • • • “Barriers to Entry,” background note to meeting of the OECD Competition Committee. March 6, 2006, OECD: DAF/COMP (2005)42. (available at www.oecd.org) Motta, Massimo, Competition Policy: Theory and Practice, Cambridge University Press, 2004 (in particular Chapter 3: “Market Definition and the Assessment of Market Power.”) Commission Decision of 24.03.2004 re: Case COMP/C-3/37.792 Microsoft US v. Microsoft Corp., US District Court for the District of Columbia,Civil Action No. 98-1232 (TPJ), No 98-1233 (TPJ); 84 F. Supp. 2d 9, (1999) Carlton, Dennis “Market Definition: Use and Abuse,” Competition Policy International Spring 2007, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 3-27. U.S. v. E.I. de Pont de Nemours & Co 351 U.S. 377 (1956) EC Case C-62/86 AKZO Chemie BV v Commission [1991] ECR I-3359, paragraph 60 37