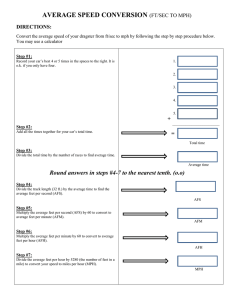

Accreditation Report

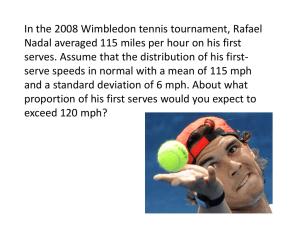

advertisement