Document

advertisement

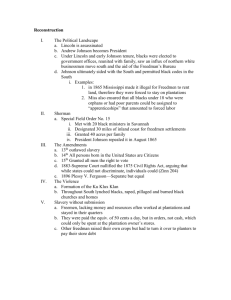

1.22.2012 History Honors—Cutler Reconstruction Civil War Reconstruction reveals some of the darkest pages in American history. President Andrew Johnson, an overt racist who, while paying lip service to his radical republican opponents, acknowledged that successful reconstruction called for “established, domestic tranquility,” and the protection o bf individual “rights of life, liberty, and property.”1 In virtually every respect, though, the federal government proved unable or unwilling to meet such lofty goals, including reforming education, redistributing land, and granting suffrage to freedmen. In essence, slavery continued to exist for all but in name. The Freedman’s Bureau, originally established by President Lincoln in 1865, did not have sufficient funding, time or manpower to make a substantial difference. Upon facing discriminatory black codes, reconstruction faced an insurmountable roadblock. Reconstruction failed, but it’s important to acknowledge that the Freedman’s Bureau did in fact make some advances. The agency served as a sounding board for freedmen, many of who still feared speaking out against whites. Most southerners felt embittered about losing the Civil War, and continued to treat freedmen as slaves. To a limited extent, the bureau helped freedmen adjust into a predominantly white aristocratic society. The bureau helped pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which declared freedmen, and “all persons born in the United States” to be citizens.2 On paper, this brought freedmen one step closer to assimilation into white society. The 1 Andrew Johnson, Plan of Reconstruction (1865), Page 2 1 2 The Civil Rights Act of 1866, Page 11 Freedman’s Bureau worked under the understanding that “if ever the negro [was] capable of rising, he [would] rise again,” and its agents did their best to provide blacks with at least some semblance of freedom to prevent another bloody conflict.3 Most importantly, the bureau also tried to distribute land that according to historian Eric Foner, they “had earned by the sweat of their brows.”4 Unfortunately, black codes and Johnson’s vetoes prevented the Freedman’s Bureau from allowing any real and lasting reform to take hold. More than anything, state-sponsored black codes severely limited the effectiveness of the Freedmen Bureau’s efforts. For the most part, this “backdoor attempt to restore slavery” succeeded in keeping recently freed blacks from enjoying freedom.5 The harshest codes existed in Mississippi, and one such law stated that “any person who shall… intermarry” would be “deemed guilty of felony” and be “[confinement] in the State penitentiary for life.” In addition, anyone “living in adultery or fornication with a freed woman” would be deemed “vagrants.”6 Outlawing intermarriage and or sexual relations with freedmen prevented blacks from truly integrating into white society. Despite more progressive federal legislation, including the reconstruction amendments, on a state level, freedmen still lacked fundamental liberties. In Mississippi, another code gave whites the power to arrest any freedman who had quit their jobs, and they could return this person to his employer for “the sum of five dollars.”7 Tasked with keeping blacks all but enslaved, whites proved their patriotism by subjugating freedmen. Any freedman over the age of 18 had to have “lawful employment” and could not be found 3 Carl Schurz, Report on Conditions in the South (1865), Page 3 Eric Foner, A Short History of Reconstruction (Harvard University Press, 2003) 12. 5 Andrew Johnson, Plan of Reconstruction (1865), Page 2 6 The Mississippi Black Codes (1865), Page 9 7 The Mississippi Black Codes (1865), Page 9 4 “unlawfully assembling” or face a fine or imprisonment. Denied first amendment protection, blacks were not allowed to converse publically---else face significant repercussions. In response to the black codes, the Freedmen’s Bureau, created in 1865, attempted and failed to garner enough political support to support educating freedmen. Lacking necessary funding under Oliver O. Howard, the agency could not build enough schools with qualified teachers. In a report to Johnson, Major General Carl Schurz said that to reach full equality, a freedman must become “intelligent “and “useful.”8 The president not only ignored the report, he proceeded to veto progressive legislation that would allow the bureau to conduct its work and help blacks realize new opportunities. Taking advantage of the extremely inadequate education system, which left most blacks illiterate, former slave owners supported black codes that forced freedmen to continue working on plantations or else face a fine, imprisonment or cruel punishment. Blacks longed to explore more attractive employment opportunities, but due to the bureau’s ineffectiveness with educational reform, freedmen remained “acquainted” with only one system of work.9 The Freeman’s Bureau also proved unable to effectively distribute land, which freedmen most associated with freedom. Land ownership proved that the titleholder could afford property and have “physical independence from their landlords,” both of which could only be accomplished by freemen earning an income. In a bold move, radical republicans attempted to confiscate property once held by white plantation owners. Progressives argued that since generations of black slaves had never received reparation for their work, they now deserved significant compensation. The Freedman’s Bureau settled over 10,000 black families, but this 8 9 Philip A. Bell, Reconstruction (1865), page 7 Carl Schurz, Report on Conditions in the South (1865), Page 5 left tens of thousands homeless. Johnson also did nothing to support progressives, who looked to use Washington’s political will to enact lasting reform. Instead, the president endorsed racist black codes to retain a horrific economic system almost identical to the antebellum period. Johnson stated that the Union should return to, “as it was and the Constitution as it [was written at the time].”10 This showed Johnsons unwillingness to form any compromise and foster any change. Former Confederate states passed unconstitutional laws that trampled upon the bureau’s efforts to give more black families even the smallest allotments of land. Johnson never invoked his or the federal government’s authority, serving to drastically diminish the bureau’s effectiveness.11 Equally as abhorrent, the Freedmen’s Bureau accomplished nothing by way of upholding the fifteenth amendment and assuring black’s suffrage. The amendment stated that the federal government would not deny any citizen the right to vote on account of “race, color, or previous conditions of servitude.”12 State-specific literary tests prevented blacks from enjoying the most fundamental right to democratically electing representatives. Whites were not required to take these tests, and many would have otherwise failed. Massachusetts Senator Thaddeus Stevens eloquently argued the importance of black suffrage: “Loyal blacks [have] as good a right to choose rulers and make laws as rebel whites.”13 In his correspondence to Johnson, Schurz also argues the blacks seek out the government as its “protector,” not as its “oppressor,” as many southern whites saw it, and that blacks look toward the government for “assurance for future 10 The Mississippi Black Codes (1865), Page 8 Alan Brinkley, The Unfinished Nation, Page 382 12 Alan Brinkley, The Unfinished Nation, Page 378 13 Thaddeus Stevens, Black Suffrage and Land Distribution, Page 13 11 prosperity and happiness.” 14 Both Stevens and Schurz argue that blacks have just as much of a right, if not more of a right, to vote than the white citizens have. Reconstruction failed and while the Freedman’s Bureau made several accomplishments, it did not bring about real, lasting reform. The Mississippi black codes denied blacks any liberties promised in the Bill of Rights. Although the Freedman’s Bureau attempted to provide education to all freedmen, the movement lacked necessary aid. Land distribution also failed because of Johnson’s unwillingness to use his executive authority to allocate land to deserving freedmen. Racist legislation also denied freedmen access to the ballot box, requiring them to pass a literary test. Even though reconstruction had potential to succeed with the creation of the Freedman’s Bureau, southern-white state governments barred freedmen from being truly free. 14 Philip A. Bell, Reconstruction (1865), page 7