Title Exhibition Road – a shared space?

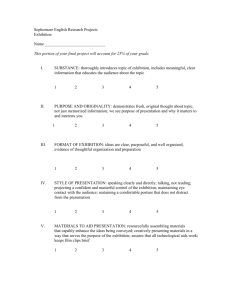

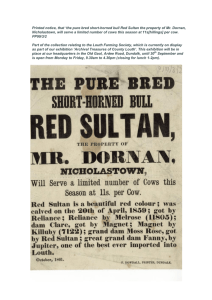

advertisement