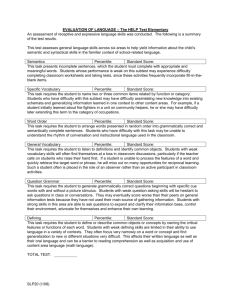

Graph 4.2 – The daily demand for proteins, carbohydrates and fats.

advertisement

Extended Essay The study of obesity among primary school pupils in Szkola Europejska Research Question: Does calorific content, amount of proteins, carbohydrates and fats in the school meals contribute to the abnormalities in body mass index among 9-12 aged pupils of Szkola Europejska in Lodz? IB Subject: Biology by …………………………… Candidate: …………………… School: Szkoła Europejska (003065) Łódź, Łódzkie, Poland Diploma Session: May 2013 Word Count: 3936 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor Mrs Marta Kamasińska for her continuous support, guidance and providing me with valuable insight into this work. I would like to thank the school nurse for letting me use her medical equipment in this research. 1 ABSTRACT: The experiment was conducted to study the obesity among primary school pupils in Szkola Europejska. The research question was formulated as: Do calorific content, amount of proteins, carbohydrates and fats in the school meals contribute to the abnormalities in body mass index among 9-12 aged pupils of Szkola Europejska in Lodz? The data was collected by measuring height and weight among 9-12 years old children and giving them a questionnaire to fill. Also school meals menus throughout a week were collected. The data collected for height and weight was calculated into BMI values and then subjected to two-tailed t-test. Subsequently, calorific content of school meals and their amount of proteins, carbohydrates and fats were calculated and their relation to the daily demand was determined. Those results were then compared to the number of hours children spent on sports. Afterwards, the time required to burn average energy value of a school meal was calculated. The calculations of BMI value among 9-12 aged children showed that average BMI varies between 5th percentile and 85th percentile, which is categorized as healthy weight. The comparison of the t-test values proved no significant difference between children’s BMI on average. Furthermore, it was showed that the daily breakfast demand for calories is met only in 48%, and in the case of lunches is met in 89%. While the average content of carbohydrates and fats in school meals is normal, the average protein content in school meals exceeds 10% of the daily demand. Moreover, the calories burned during normal activity exceed the average number of calories consumed in school meals. The results indicated that school meals do not contribute to the BMI abnormalities among 9-12 aged children and they do not exceed the daily demand for calories. Nonetheless, the tendency to consume low-calories breakfasts and high-calories lunches was manifested. Word count: 302 2 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION……..………………………………..................................................6 1.1 Research question……..………………………………..................................................……………6 1.2 Genesis of the work..………..………..………..………..………..………..………..………..………..…6 1.3 Theoretical background………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..…………7 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..….11 2.1 Objectives of the study………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..…………11 2.2 Hypothesis………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..………..11 2.3 Variables………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..11 2.4 Materials………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..12 2.5 Procedures………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..………..12 2.6 Statistical analysis………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………13 CHAPTER 3: DATA COLLECTION AND PROCESSING………..………..………..…………14 3.1 Raw data for children………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..…14 3.2 Raw data for school meals………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..……15 3.3 Raw data for practiced sports………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..18 CHAPTER 4: ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION:………..………..………..…………..…...19 4.1 BMI calculations:………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..…………19 4.2 Food calculations:………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..24 4.3 Sport calculations:………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..……….27 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION AND EVALUATION………..………..………..…………..………29 5.1 Hypothesis I………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..………29 5.2 Hypothesis II………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..……..29 5.3 Caloric content of school meals ………..………..………..…………..………………..…………30 5.4 BMI………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..……….30 5.5 Sport………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..……..30 5.6 Evaluation………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………32 3 BIBLIOGRAPHY………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..………33 Appendix 1………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..……………..34 Appendix 2………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..……………..35 Appendix 3………..………..………..…………..………..………..…………..………..………..……………..36 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Research question: Does calorific content, amount of proteins, carbohydrates and fats in the school meals contribute to the abnormalities in body mass index among 9-12 aged pupils of Szkola Europejska in Lodz? 1.2 Genesis of the work: According to recent research, the number of overweight children in Poland has increased three times over the past 20 years. It was estimated that the scale of the obesity problem in Polish schools is coming closer to the one in America. While in the United States, the percentage of children suffering from obesity is over 20%, in Poland the issue applies to 18% children1. Furthermore, the consequences of obesity among Polish children slowly begin to emerge: the majority of them suffer from respiratory distress, hypoxia, hypertension, high cholesterol and dysfunction of glucose metabolism. They eat too much salt, saturated fats and sugar, and not enough fibre and unsaturated fats2. Under the influence of these studies, I began to contemplate what is the determining factor of obesity among children. When I started to look for the reasons behind this problem, I came across a large amount of articles3 that suggested that one of the factors causing obesity among children is the food served in schools. I was intrigued whether in my school, the school meals contribute to weight problems among children of the primary school. Therefore, 1 http://zdrowie.dziennik.pl/profilaktyka/artykuly/408809,trzykrotnie-wzrosla-liczba-otylych-dzieci-w-polsce- warszawa-chce-walczyc-z-nadwaga-i-otyloscia-w-szkolach.html 2 http://www.farmacjaija.pl/zdrowie/co-powinny-jesc-dzieci.html 3 http://children.webmd.com/news/20100315/school-lunches-linked-to-kids-obesity 4 a thorough study of the relationship between the consumption of meals at school and the tendency to be overweight should be done. 1.3 Theoretical background: Body Mass Index Body Mass Index (BMI) or Quetelet index, is an estimate of body composition used extensively as an indicator of whether an individual is clinically classified as obese. The Body Mass Index is defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of their height in metres4. 𝐵𝑀𝐼 = 𝑚𝑎𝑠𝑠 [𝑘𝑔] (ℎ𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡 [𝑚])2 Estimating the BMI for children slightly differs from the one for adults, given that a child’s BMI changes while they mature. In children, the child’s age is necessary in order to compare the obtained result to typical values for children of the same age. Instead of fixed thresholds for underweight and overweight such as those used for adults, the BMI percentile indicates the relative position of …………., etc Importance of breakfast and lunch consumption Eating breakfast is the most optimal way to meet the energy needs of the body. Daily consumption of breakfasts provides a better functioning of the digestive and circulatory system and improves the ability to concentrate. If an individual does not provide the body with food in a breakfast, in their empty stomachs hypersecretion of acid occurs, therefore causing mucous membrane irritation and disruption of the digestive system. Resistance to cold decreases and the concentration of glucose in the blood decreases, which can lead to dizziness or even fainting. For this reason, some people may prove themselves to be less efficient at work or school. The research that was carried out on a group of several hundreds of British has confirmed that regular breakfast consumption improves mood and well-being5. Two experimental groups were set up, both of which 4 Michael Kent, Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science & Medicine Second Edition, page 74 5 http://www.masaz.toskar.info/sniadanie-najwazniejszym-posilkiem-dnia.php 5 ate according to their previously calculated energy requirements. The only difference between the two groups lied in the fact that one group ate their entire portion of calories in the morning (provided in a large breakfast), and the other group, for dinner. The group that ate in the evening gained weight, whereas the other group that ate in the morning lost weight, even though they all ate as much as their body theoretically needed. Therefore, in order to maintain a constant weight, the amount of food consumed is as essential as the way it affects the metabolism. The sooner the body is provided with food, the more the body is set to burn the energy supplied to it, however, the later there is a greater tendency of body fat deposition. Daily breakfast consumption increases the metabolism from 3 to 10%, consequently, we can gain or lose 10 pounds on an annual basis6. The benefits of regular breakfast consumption: Better resistance to stress Immune system is more efficient Nervous system is more efficient Helps in maintaining healthy weight Controls hunger throughout a day Reduces the likelihood of overeating In Poland, the tendency to eat low-calories breakfasts and high-calories lunches is manifested. According to recent research conducted in Poland, 22% of parents claimed that their children do not eat breakfast three out of five days a week. Only slightly more than half of the parents make sure that their children do not come to school hungry. Moreover, 95% of children between 6 and 11 years old, do not consume lunch at school, and one in five Poles do not eat breakfast at all7. Daily demand for calories and the role of essential nutrients in the human body Calories The recommended food ration is deliberately chosen set of products, including their amount in order to cover the body’s daily requirement for all nutrients. The 6 http://www.masaz.toskar.info/sniadanie-najwazniejszym-posilkiem-dnia.php 7http://metromsn.gazeta.pl/Lifestyle/1,126513,12818816,Polacy_nie_jedza_sniadan__To_niezdrowo__Jak_ich_zacheci c.html 6 recommended daily calories intake for children aged 9-12 years is 2300 cal. Depending on the number of meals per day, breakfast should coincide 25-35% and lunches 15-30% of total daily caloric intake8. Proteins Protein is the basic structure of all living cells. It is an important part of cell membranes, blood (haemoglobin) and enzymes. Proteins determine the growth of young organisms and support the growth of hair, nails and help in reconstruction of damaged skin epithelium and healing of wounds. Antibodies are made up of proteins, therefore they play protective role in the organism. The effects of protein deficiency include……., etc Carbohydrates Carbohydrates are the main source of energy to the body, providing approximately 5060% of the energy. Deficiency of carbohydrates in a diet is harmful to the body and reveals itself primarily as a feeling of hunger, general weakness, fainting, muscle tremor and convulsions. The symptoms of hypoglycemia are related to the shortage of sugar as the basic energy material for muscles and nerve cells. At least one third of daily calories should come from energy supplied by carbohydrates. It is estimated that ………, etc Fats Fats play important role in the human body. They provide a significant amount of energy (20 to 35%). One gram of fat gives the body 37.7 kJ of energy; approximately twice as much as proteins and saccharides. Fats are also a major source of essential fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K). Some fatty acids are involved in the synthesis of certain hormones tissues, such as prostaglandin. Fats in moderate amounts are the essential human nutrients. They are the main source of ………………, etc CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY 2.1 Objectives of the study: To calculate the caloric content of school meals. Wiesław Graban, Witold S. Gomułka, Encyklopedia Zdrowia, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa 2001, page 383 8 7 To estimate the average number of hours spent by children on sport activities. To verify how much exercise is needed to burn the average school meal To check whether school meals are appropriate for pupils of particular age. 2.2 Hypothesis: HYPOTHESIS 1: School meals exceed the daily breakfast and lunch demand for calories and daily demand for proteins, carbohydrates and fats. HYPOTHESIS 2: School meals have too many calories to be burnt during the pupil’s normal activity. 2.3 Variables: Table 2.1 – Independent, dependent and controlled variables in the experiment Independent Variables Subjects School meals The number of hours Dependent Variables Controlled Variables Body mass index (BMI) The between 9 and 12 amount proteins, children carbohydrates Weight [kg] fats in school meals Height [m] [g] Age Gender Caloric years old) of spent on sports by Age group (children and content Length of experiment (5 days) of school meals [kcal] 2.4 Materials: Stadiometer Medical Scale CDC Body Mass Index-For-Age Percentiles for boys (2 to 20 years) (Appendix 1) 8 the CDC Body Mass Index-For-Age Percentiles for girls (2 to 20 years) (Appendix 2) Texas Instruments TI-84 Plus Food calorie table Questionnaire (Appendix 3) Letter to parents asking for permission to conduct research on their children (Appendix 4) 2.5 Procedures: Procedure 1 – Medical examination of the children 1. Before the experiment begins, ask the parents for permission to conduct the research on their children. 2. Having a parental consent, collect a group of children between the ages of 9 to 12 years (five or more in each age group). 3. Measure the height and weight of each child using stadiometer and medical scale. 4. Give them previously prepared questionnaire about sports they practice. 5. Having collected all the data, calculate each child’s BMI and plot it on CDC Body Mass Index-For-Age Percentiles growth chart for either boys or girls, in order to find out the percentile range and weight status category of a particular child. 6. Calculate the amount of …………………., etc Procedure 2 – School meals 1. Everyday for one week, collect the school meals menu of food that children consume. 2. Once all the data is collected calculate the caloric content of school meals using food calorie table. 3. Calculate how much protein, fats and carbohydrates those meals contain. 4. Compare the obtained results with daily food intake for various calorie demands. 5. Evaluate the results. 2.6 Statistical analysis Mean: 𝑥= Σ𝑥 𝑁 Standard deviation: 9 𝜎=√ ∑(𝑥 − 𝑥)2 𝑁 T-test: 𝑡= (𝑥𝑚𝑒𝑎𝑛1 − 𝑥𝑚𝑒𝑎𝑛2 ) 2 2 √ 𝑆1 + 𝑆2 𝑛1 𝑛2 CHAPTER 3: DATA COLLECTION AND PROCESSING …………………………………………………………………………..…….. …………………………………………………………………………………. CHAPTER 4 – ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION 4.1 BMI calculations As it can be seen in tables 4.1-4.4, information about BMI of children aged 9-12 years old, is presented. BMI was calculated using the following formula: 𝑚𝑎𝑠𝑠 [𝑘𝑔] 𝐵𝑀𝐼 = (ℎ𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡 [𝑚])2 . The obtained values were then marked on the CDC Body Mass Index-For-Age Percentiles growth charts in order to receive a percentile ranking and weight status category of children. Table 4.1 – BMI, percentile range and weight status category for 9 years old children 9 year old children 1 2 3 4 5 Average SD BMI Percentile range Weight status category 17 20 14 15 15 16 2.17 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 85th to less than the 95th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile Healthy weight At risk of overweight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight 10 Table 4.2 – BMI, percentile range and weight status category for 10 years old children 10 year old children 1 2 3 4 5 6 Average SD BMI Percentile range Weight status category 15 20 20 16 17 17 15 6.66 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 85th to less than the 95th percentile 85th to less than the 95th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile Healthy weight At risk of overweight At risk of overweight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight Table 4.3 – BMI, percentile range and weight status category for 11 years old children 11 year old children 1 2 3 4 5 6 Average SD BMI 26 20 17 15 15 17 18 3.88 Percentile range Weight status category Greater than or equal to the 95th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile Overweight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight Table 4.4 – BMI, percentile range and weight status category for 12 years old children 12 year old children 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Average SD BMI Percentile range Weight status category 18 19 18 20 21 18 20 19 1.22 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 85th to less than the 95th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight At risk of overweight Healthy weight Healthy weight Healthy weight In order to establish if the difference between children’s BMI is significant, a two-tailed Student’s t-test is performed. Based on BMI values of 9 and 10 years old children, a test of comparing the mean and standard deviation of two sets of samples to see whether 11 they are equivalent or different, is conducted. A value for t is calculated using a statistical formula: 𝑡= (𝑥𝑚𝑒𝑎𝑛1 − 𝑥𝑚𝑒𝑎𝑛2 ) 2 2 √ 𝑆1 + 𝑆2 𝑛1 𝑛2 The result of t-test for BMI values of 9 and 10 years old children came out as follows: Table 5 – Example calculations for the t-test Body Mass Index (𝑥 − 𝑥̅ )2 𝑥 𝑥 − 𝑥̅ 9 year old 10 year old 9 year old 10 year old 9 year old 10 year old children children children children children children 17 15 1 -3 1 9 20 20 4 2 16 4 14 20 -2 2 4 4 16 -1 -2 1 4 15 15 17 -1 -1 1 1 17 -1 1 2 23 23 ∑(𝑥 − 𝑥̅ ) 𝑛9 = 5 𝑛10 = 6 Figure 2 – Example calculations for the t-test 1. State the null and alternative hypothesis 𝐻0 = 𝜇𝐵𝑀𝐼 𝑜𝑓 9 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 𝑐ℎ𝑖𝑙𝑑𝑟𝑒𝑛 = 𝜇𝐵𝑀𝐼 𝑜𝑓 10 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 𝑐ℎ𝑖𝑙𝑑𝑟𝑒𝑛 𝐻𝐴 = 𝜇𝐵𝑀𝐼 𝑜𝑓 9 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 𝑐ℎ𝑖𝑙𝑑𝑟𝑒𝑛 ≠ 𝜇𝐵𝑀𝐼 𝑜𝑓 10 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 𝑐ℎ𝑖𝑙𝑑𝑟𝑒𝑛 2. Calculate the variances 𝑆92 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 Σ(𝑥 − 𝑥̅ )29 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 = 𝑛9 − 1 2 𝑆10 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 = 2 Σ(𝑥 − 𝑥̅ )10 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 𝑛10 − 1 12 23 = 5.75 5−1 23 = = 4.60 6−1 𝑆92 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 = 2 𝑆10 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 3. Calculate the actual difference between means (𝑥9 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 − 𝑥10 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑) = 5.75 − 4.60 = 1.15 4. Calculate the t value 𝑡= (𝑥𝐵 − 𝑥𝐴 ) 2 2 √ 𝑆9 + 𝑆10 𝑛9 𝑛10 = 1.15 √5.75 + 4.60 6 5 = 0.83 5. Determine degrees of freedom d.f. (𝑛9 + 𝑛10 − 2) = (5 + 6 − 2) = 9 6. Consult the t-table For the calculation of Body Mass Index, the calculated value of t=0.83 is lower than the critical value=2.26, therefore there is no significant difference between BMI of 9 years 13 old children and 10 years old children on average and we do not reject 𝐻0 = 𝜇𝐵𝑀𝐼 𝑜𝑓 9 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 𝑐ℎ𝑖𝑙𝑑𝑟𝑒𝑛 = 𝜇𝐵𝑀𝐼 𝑜𝑓 10 𝑦𝑒𝑎𝑟𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑 𝑐ℎ𝑖𝑙𝑑𝑟𝑒𝑛 . Average Body Mass Index (BMI) Graph 4.1 – Average Body Mass Index (BMI) for 9-12 years old children. 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 18 18 19 16 9 years old children 10 years old children 11 years old children 12 years old children Age group Average BMI value in children aged 9 years is 16, which is 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile in percentile range and it is categorized as healthy weight. In the case of 10 and 11 year-olds, average BMI value is estimated to be 18, which is also classified as healthy weight. In 12 year-old children, average BMI value is 19 and it is categorized as healthy weight as well. Among the 24 children examined, subject 1 (11 years old) is the only one whose BMI percentile is greater than or equal to the 95th percentile, which is categorized as overweight in weight status category. In the case of subject 2 (9 years old), subject 2 and 3 (10 years old) and subject 5 (12 years old) BMI percentile is 85th to less than the 95th percentile in percentile range, which is classified as at risk of overweight. Those children who deviate from the average represent 21% of all examined children and a child, whose BMI is in the extreme value of 10% on the upper side of the CDC BMI growth charts (above the 95th percentile) require careful observation. 14 4.2 Food calculations Average energy value of food, proteins, carbohydrates and fats obtained from both breakfasts and lunches was calculated using the following formula: 𝑥 = Σ𝑥 𝑁 Table 4.5 – Average energy value of food, proteins, carbohydrates and fats Day of the week Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Average SD Graph 4.2 – Energy value of food [cal] (±0.01) 949.50 1075.48 1054.26 963.81 956.39 999.89 53.67 The daily demand Proteins [g] (±0.01) 48.09 57.67 41.06 44.73 58.54 50.02 6.97 for proteins, Carbohydrates [g] (±0.01) 110.08 83.06 104.37 76.09 120.26 98.77 16.63 carbohydrates Fats [g] (±0.01) 33.77 59.34 54.20 52.81 30.05 46.03 11.79 and fats. The percent daily value for essential nutrients (%) 120% 110% 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 110% 40% 72% 30% 20% 34% 10% 0% Proteins Carbohydrates Essential nutrients Fats As it can be seen on the graph above, average protein content in school meals exceeds 10% of the daily demand for proteins. Daily requirement for carbohydrates is met in 34% and in the case of fats, the daily demand is met in 72%. 15 Graph 4.3 – The percent daily demand for calories The percent daily caloric value for school meals (%) 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 47 41 46 42 42 10 0 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Energy value of food [cal] Friday The graph 4.3 presents the percent daily demand for calories in comparison to the percent caloric content of food served in school. The values are roughly approximate to each other, ranging between 40 and 50%. On Monday, daily demand for calories is met in 41%, which makes it the lowest value, whereas on Tuesday, it is met in 47%, which makes it the highest value. Graph 4.4 – The percent daily demand for breakfasts The percent daily demand for breakfasts and lunches (%) 160 140 120 100 80 134 60 40 67 20 0 Breakfasts Lunches 16 and lunches The graph 4.4 demonstrates the average percent daily demand for breakfasts and lunches obtained from school meals. The daily breakfast demand for calories is met in 48% and the daily lunch demand for calories is met in 89%. 4.3 Sport calculations As it can be seen in graphs 4.5 and 4.6 energy balance of the body is calculated. Energy balance is the difference between the amount of energy delivered to the body in food in the form of carbohydrates, fats and proteins, and the amount of energy expended by the body in the form of work and heat, in the same period of time. Graph 4.5 – Comparison of the average number of calories burned through physical activity with an average caloric content of meals. 1014 1012 1010 Calories [cal] 1008 1006 1004 1012 1002 1000 998 1000 996 994 Average calories burned through physical activity Average calories consumed in a school meal As it can be seen on the graph 4.5 the average number of calories burned through a physical activity exceeds the average number of calories consumed in school meals. Therefore, energy balance is balanced because both sides are approximately equal. 17 Graph 4.6 – The time required to burn average energy value in a school meal. Brisk walking 550 Swimming 210 Cycling (20 km/h) 140 0 100 200 300 400 Time in minutes 500 600 The graph above shows how much an individual has to spend on a particular sport in order to burn average caloric content of a school meal (999.89 cal). To burn the calories consumed in shortest time possible, a child has to spend 140 minutes cycling at the speed of 20 km/h, whereas, brisk walking takes the longest time to burn the energy value of food. CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION AND EVALUATION 5.1 Hypothesis I The hypothesis I states that school meals exceed the daily breakfast and lunch demand for calories and the daily demand for proteins, carbohydrates and fats. The graphs and the processed data demonstrate that the daily breakfast demand for calories is met only in 48%, therefore children obtain only half of the calories needed for their bodies to function properly. In the case of lunches, the daily demand for calories is met in 89%, which is fairly close to meeting the daily requirement. Therefore, the statement that in Poland there is a tendency to eat low-calories breakfasts also applies to children, who go to Szkoła Europejska. However, as far as the daily demand for proteins, carbohydrates and fats is concerned, presented data clearly show that average protein content in school meals exceeds 10% of the daily demand. Once again it must be emphasized that it 18 is not known whether children exceed this limit even further consuming more proteins at home. The excessive consumption of proteins is as harmful as its deficiency and it results in metabolic disorders, such as acidosis and it also increases the risk of obesity. Therefore, school ought to reduce the amount of proteins in the school meals and increase the amount of carbohydrates intake, which as the data demonstrate, meets the daily demand only in 34%. From a health point of view, reducing the consumption of carbohydrates is incorrect and unhealthy. Carbohydrates are not only a source of energy for neurons but also facilitate fat burning. As far as fats are concerned, the daily demand is met in 72% and it seems to be in sufficient quantity. Therefore, the hypothesis that school meals exceed the daily breakfast and lunch demand for calories and the daily demand for proteins, carbohydrates and fats must be rejected for calories, carbohydrates and fats, but accepted for proteins. 5.2 Hypothesis II The hypothesis II states that school meals have too many calories to be burnt during the pupil’s normal activity. The graphs and the processed data demonstrate that calories burned during the pupil’s normal activity exceed the average number of calories consumed in school meals. Therefore, the hypothesis must be rejected. However, the data are not entirely accurate given the fact that some of the children examined in a particular week did not practice sport at all and children who practiced a large amount of sport made up that average. If the data for each child was calculated separately, whether the hypothesis is either accepted or rejected would be different for each child. 5.3 Caloric content of school meals The graphs and the processed data demonstrate that the daily demand for calories is met approximately in 41-47%, therefore children get only half of the calories they need in order for their body to function properly. Nonetheless, the experiment involved only the food consumed in the school cafeteria and did not include meals consumed outside of school. Consequently, it is not know whether children generally exceed or fall within the limit of the daily demand for calories, however, the school meals certainly do not exceed this limit. 5.4 BMI 19 Considering children’s BMI value, the average BMI is in 5th percentile up to the 85th percentile range for each age group, which is categorized as healthy weight. Furthermore, the t-test showed that there is no significant difference between children’s BMI values of each age group on average. Nonetheless, there are four subjects that deviate from the average. However, it is unlikely that school meals have contributed to the abnormalities in their Body Mass Index. As I have mentioned before, it is not known what children consume outside the school and what time of day they eat, therefore, it is possible that home-prepared food could affect their BMI. Furthermore, the experiment did not include whether children have health conditions such as hypothyroidism, which contribute to weight gain, thus it is not known precisely what factors could affect their BMI. Moreover, health weight range of BMI is in a fairly wide range, in order to take into account people of different physical characteristics. Nonetheless, like in any other mathematical formula, BMI calculations have some limitations; people with genetically determined thick bones tend to have overestimated value of BMI and it does not include muscle and water mass. 5.5 Sport Calculations concerning time required to burn average energy value in a school meal are approximate and in most cases not much useful if they are not verified in practice. It is due to the fact that every human body is different and they differ from each other in number of factors, in which the greatest impact is the error in the calculations of the rate of metabolism and the composition of other body tissues. All the calculations above are purely theoretical and tentative. Only exercise in controlled laboratory conditions, where calorimetric energy change, the composition of exhaled air and a number of other factors are tested, can give accurate values. Counting and burning calories predictions are useful in the initial planning stage of exercising, but then all of the calculations should be verified in practice by observing increase and decrease of both fat and lean body mass, and on this basis, the amount of exercise should be controlled. 5.6 Evaluation Factor BMI calculations Effect on Experiment Improvement Due to the fact that BMI Use 20 other body fat calculation does not include measurement methods, bones, muscle and water mass, such as bioelectrical it is possible that it gave impedance analysis. overestimated values. Children School meals Children’s approach towards the questionnaire was trivial, and consequently it gave inaccurate results, therefore children had to re-answer the questionnaire. Weight of each product was given by those preparing meals, which then affected the accuracy of calculations of the amount of calories a particular product had and therefore the whole amount of calories in school meals. Perform a study on children in adolescence. Measure the weight of each product using weighting scales in order to obtain accurate values. Bibliography 1. Wiesław Graban, Witold S. Gomułka, Encyklopedia Zdrowia, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa 2001 2. Michael Kent, Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science & Medicine Second Edition, Oxford University Press 1998 3. http://metromsn.gazeta.pl/Lifestyle/1,126513,12818816,Polacy_nie_jedza_sniad an__To_niezdrowo__Jak_ich_zachecic.html 4. http://zdrowie.dziennik.pl/profilaktyka/artykuly/408809,trzykrotnie-wzroslaliczba-otylych-dzieci-w-polsce-warszawa-chce-walczyc-z-nadwaga-i-otyloscia-wszkolach.html 5. http://www.farmacjaija.pl/zdrowie/co-powinny-jesc-dzieci.html 6. http://children.webmd.com/news/20100315/school-lunches-linked-to-kidsobesity 7. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childr ens_bmi.html#What%20is%20BMI%20percentile 21 Appendix 1 22 Appendix 2 23 Appendix 3 1. Did you practice sport throughout the week? If so, please specify. ☐Yes: ____________ ☐No* 2. How much time have you devoted your time to practice the aforementioned sport? ☐______________ 3. Did you attend physical education classes this week? ☐Yes ☐No *If you have chosen this answer, you are not obliged to answer next questions. Appendix 4 Dear __________, My name is Eleonora U. …………….. and I am a student of International Baccalaureate program in Szkola Europejska in Lodz. Under this program, I am obliged to write a research paper of a topic of my interest, which in my case is The Study of Obesity Among Primary School Pupils in Szkola Europejska. In order to conduct my research, I need your permission for your child to be medically examined. It would involve measuring the height and weight of your child and launching of a questionnaire. All information will be anonymous. If you agree to have your child examined, please put your signature in a designated area. I give my permission for my child to undergo medical examination. Signature:__________________________________ 24