Myth, Identity and Revolution

advertisement

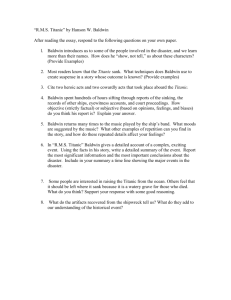

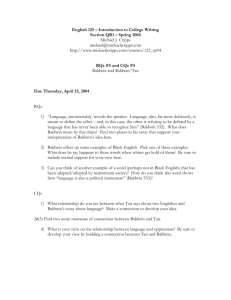

Running head: MYTH, IDENTITY AND REVOLUTION Myth, Identity and Revolution Vance Holmes Metropolitan State University Urban Teacher Program EDU 630 Paul Spies, Ph. D. April 20, 2011 Contact: Vance Holmes, 1500 LaSalle Avenue #320 Minneapolis, MN 55403 Email: vance@vanceholmes.com 1 MYTH, IDENTITY AND REVOLUTION 2 Myth, Identity and Revolution James Baldwin’s essay on education, A Talk to Teachers, is a devastatingly concise call for schools to revolutionize and serve as engines of self-realization, social justice and resistance. Although published 50 years ago, Baldwin’s piece could be an article written for today’s New York Times op-ed page. On his way to defining the purpose of education – and defending the call for revolution -- Baldwin focuses on three crisis points: social mythology, cultural identity and personal responsibility. The scope and conclusions of Baldwin’s education assessment are consistent with many other writers on the topic of the purpose of schools, but through his isolation of the key paradoxes at play, Baldwin is able to navigate the wide-ranging foundational issues of urban education in about 20 paragraphs. The essay is so condensed, each sentence within each paragraph reads like a stand-alone quotation, including Baldwin’s very first line: “Let’s begin by saying that we are living through a very dangerous time” (Baldwin, 1963). Baldwin bypasses any talk of multicultural curricula or culturally responsive classroom management and starts with the silent threat presented by the basic contradictions in American society. While we claim to value schooling, education serves the purpose of creating individuals who think for themselves, and as Baldwin points out, “no society is really anxious to have that kind of person around.” Schooling is thought to be of such importance that every child is compelled to attend, yet as Baldwin states: "Any Negro who is born in this country and undergoes the American educational system runs the risk of becoming schizophrenic.” On the one hand, the Black student goes to school and pledges allegiance to the flag. On the other hand, the Black child is made to believe that he or she has never contributed anything worthwhile to society – that the child’s past “is nothing more than a record of humiliations gladly endured.” Confronted with this paralyzing paradox, and facing the fact that there is little to be done about MYTH, IDENTITY AND REVOLUTION 3 it, Black children often fall silent as a coping strategy. They “more or less accept it with an absolutely inarticulate and dangerous rage inside” Baldwin says, “all the more dangerous because it is never expressed.” Baldwin warns that this means “there are in this country tremendous reservoirs of bitterness” which have never had an outlet. Throughout his essay, Baldwin explores the personal psychological damage produced by our cultural contradictions. He asserts that Black children come to realize the value they have as men and women of color "is proven by one thing only – their devotion to white people." Along with creating citizens who harbor a silent rage, our social schizophrenia creates criminals – people who, finding themselves in a society with standards which are not honored, choose to live outside the law. In detailing America’s identity crisis, Baldwin also touches on the psychological damage done to Whites. “If, for example, one managed to change the curriculum in all the schools so that Negroes learned more about themselves and their real contributions to this culture” he writes, “you would be liberating not only Negroes, you’d be liberating white people who know nothing about their own history.” Baldwin charges that what passes for identity in White America is “a series of myths” about heroic founding fathers. He says “we have a whole race of people, a whole republic, who believe the myths to the point where even today they select political representatives, as far as I can tell, by how closely they resemble Gary Cooper.” Perhaps the most important theme running through A Talk to Teachers is the paradox of response and responsibility. Having cited the social and personal danger in clinging to myth, Baldwin asserts that the nation is “desperately menaced” -- not by outside forces "but from within." He advises responsible citizens within the education system that they must be prepared to fight tirelessly against that system. “You must understand that in the attempt to correct so many generations of bad faith and cruelty, when it is operating not only in the classroom but in MYTH, IDENTITY AND REVOLUTION 4 society,” he writes, “you will meet the most fantastic, the most brutal, and the most determined resistance.” Baldwin speaks of the principle irony of education, saying that “precisely at the point when you begin to develop a conscience, you must find yourself at war with your society.” The responsibility of every educated citizen, Baldwin asserts, is revolution. The only rational response to a society built on duplicity and sustained by contradictory fictions is to fight for truth to prevail. Instead of withdrawing into a paralyzing silence, or joining the criminal conspiracy, we can choose to be responsible for and responsive to our society by working to change it – “at no matter what risk.” James Baldwin is decidedly unambiguous in answering the question – “What is the purpose of schools?” His viewpoint is identified in the three significant elements of his essay: mythology, identity and responsibility. Sounding like an urban education essay written last week, Baldwin forcefully declared a half century ago that schooling should have nothing to do with instructing individuals. He clarified that the purpose of education is to construct individuals – to create in each student the ability to look at the world for him or herself. “To ask questions of the universe” Baldwin explained, “and then learn to live with those questions.” MYTH, IDENTITY AND REVOLUTION 5 References Baldwin, J. (1963). A Talk to Teachers. The Saturday Review, 21, pp. 42-44.