Antibiotic resistance and medicinal drug policy

advertisement

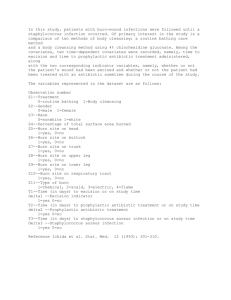

Antibiotic Resistance and Medicinal Drug Policy Dr. Ken Harvey School of Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia 1 Lecture outline • Why the concern about antibiotic resistance? • The history, microbiological and social determinants of antibiotic resistance • Containing antibiotic resistance: microbiological surveillance, antibiotic utilization studies and other interventions • One country’s response: the quality use of medicines pillar of Australian drug policy • The current challenge – using information technology to further improve antibiotic use 2 Press Release WHO/41 12 June 2000 DRUG RESISTANCE THREATENS TO REVERSE MEDICAL PROGRESS Curable diseases – from sore throats and ear infections to TB and malaria -- are in danger of becoming incurable A new report warns that increasing drug resistance could rob the world of its opportunity to cure illnesses and stop epidemics. 3 The start of antibiotic resistance: Penicillin Fleming 1928 Florey & Chain 1940 4 History of resistance 1941 1943 1945 1950 1952 1956 Penicillin Streptomycin Cephalosporins Tetracyclines Eryrthromycin Vancomycin 1960 1962 1962 1970 1980 2010 Methicillin Lincomycin Quinolones Penems Monobactams The end of the antibiotic era? 5 Bacterial evolution vs mankind’s ingenuity • Adult humans contains 1014 cells, only 10% are human – the rest are bacteria • Antibiotic use promotes Darwinian selection of resistant bacterial species • Bacteria have efficient mechanisms of genetic transfer – this spreads resistance • Bacteria double every 20 minutes, humans every 30 years • Development of new antibiotics has slowed – resistant microorganisms are increasing 6 Surveillance of resistance: Australia Data are collected from 29 laboratories around Australia, including public hospital and private laboratories, in both metropolitan and country areas. Australia, like China, is a contributor to the WHO A-R Infobank: http://oms2.b3e.jussieu.fr/arinfobank/ 7 Resistance: Australia 2000 • Hospitals – vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE’s) – multi-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA) NB. vancomycinresistant strains have been found in Japan and the USA but not yet in Australia • Community – Strep. Pneumoniae (Penicillins 15% I, 2% R; macrolides & tetracyclines 20% R) – Haemophilis influenzae (Penicillins 20% R ; macrolides & tetracyclines 10% R) – E. coli (amoxycillin 45% R ; amoxy-clav 10% R ; trimeth 15%R) 8 Resistance: The World 2000 • In much of South-East Asia, resistance to penicillin has been reported in up to 98% of gonorrhoea strains. • In Estonia, Latvia, and parts of Russia and China, over 10% of tuberculosis (TB) patients have strains resistant to the two most effective anti-TB drugs. • Thailand has completely lost the use three of the most common anti-malaria drugs because of resistance. • A small but growing number of patients are already showing primary resistance to AZT and other new therapies for HIV-infected persons. 9 The consequences of antibiotic resistance • Increased morbidity & mortality – “best-guess” therapy may fail with the patient’s condition deteriorating before susceptibility results are available – no antibiotics left to treat certain infections • Greater health care costs – more investigations – more expensive, toxic antimicrobials required – expensive barrier nursing, isolation, procedures, etc. • Therapy priced out of the reach of some third-world countries 10 Therapy priced out of the reach of the poor • A decade ago in New Delhi, India, typhoid could be cured by three inexpensive drugs. Now, these drugs are largely ineffective in the battle against this life-threatening disease. • Likewise, ten years ago, a shigella dysentery epidemic could easily be controlled with cotrimoxazole – a drug cheaply available in generic form. Today, nearly all shigella are non-responsive to the drug. • The cost of treating one person with multidrug-resistant TB is a hundred times greater than the cost of treating nonresistant cases. New York City needed to spend nearly US$1 billion to control an outbreak of multi-drug resistant TB in the early 1990s; a cost beyond the reach of most of the world's cities. 11 Social factors fuelling resistance • Poverty encourages the development of resistance through under use of drugs – Patients unable to afford the full course of the medicines – Sub-standard & counterfeit drugs lack potency • In wealthy countries, resistance is emerging for the opposite reason – the overuse of drugs. – Unnecessary demands for drugs by patients are often eagerly met by health services and stimulated by pharmaceutical promotion – Overuse of antimicrobials in food production is also contributing to increased drug resistance. Currently, 50% of all antibiotic production is used in animal husbandry and aquiculture • Globalization, increased travel and trade ensure that resistant strains quickly travel elsewhere. So does excessive promotion. 12 Postponing the end of the antibiotic era • Antibiotic stewardship (prudent use) • Contain the spread of resistant microorganisms and relevant genes (infection control) • Develop new antibiotics that have novel modes of action or circumvent bacterial mechanisms of resistance (research) 13 Antibiotic stewardship: Australia 14 What are Antibiotic Guidelines? • Best practice recommendations concerning the treatment of choice for common clinical problems • Written by national experts • Evidence based where possible, peer-consensus where not • Regularly updated every 2 years • Endorsed by the Australian Medical Association, etc. • Used for medical education, problem look-up and drug audit 15 Drug audit, and change strategies Compare drug use with Guidelines recommendations Identify issues Implement change strategies Develop consensus approach 16 First Australian drug audits:1978-82 • The 700 bed Royal Melbourne Hospital was surveyed. The 240 bed sample comprised: – 3 general medical units – gastroenterology unit – haematology-oncology unit – 4 general surgical units – orthopaedic unit 17 Inappropriate prescribing • Example of a drug not required: – A patient with suspected infected burns received oral flucloxacillin and penicillin V. Therapy was continued for 23 days despite the failure of 3 separate swabs to produce any growth on culture. Culture of the fourth swab grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. 18 Inappropriate prescribing Example of incorrect administration: Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis accounted for 100 prescriptions and, of these, 23 were given 2 to 12 hours AFTER the operation, a delay that largely nullified their value. Example of inadequate cover: A patient received gentamicin for peritonitis, thereby ignoring the anaerobic flora of the bowel. Metronidazole or clindamycin should have been added 19 Change strategies used • Feedback of audit results to prescribers followed by discussion at grand rounds and unit meetings • Use of Antibiotic Guidelines in undergraduate and postgraduate teaching • Rewriting the next edition of Antibiotic Guidelines, incorporating additional text to clarify misunderstandings and problems observed 20 Audit results Patients receiving antibiotic therapy 40 30 20 10 0 1978 1982 percentage of patients receiving antibiotic therapy 21 Audits results Percentage of appropriate treatments 80 60 40 20 0 1978 medical wards 1982 surgical wards total 22 Initial conclusions • Antibiotic prescribing improved • Surgeons (prophylaxis) were responsible for more inappropriate prescribing than physicians • Some persisting patterns of inappropriate antibiotic use appeared to reflect pharmaceutical company promotion • There was also a need for ongoing campaigns because hospital staff changed 23 Australian therapeutic guidelines: Today 24 Dr. Harvey’s visit to China was sponsored by The World Health Organization and hosted by Professor Yong-Hong Yang Beijing Children’s Hospital & Professor Li Dakui Peking Union Medical College 25