Iara Cury Anthropology of Development 2/5/2011 Education

advertisement

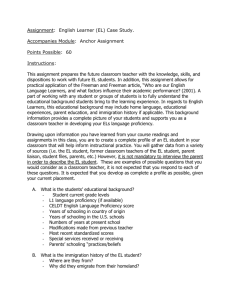

Iara Cury Anthropology of Development 2/5/2011 Education: Liberation or Coercion? Around the world, the discourse that acquiring an education entails going through a number of years of schooling and is a positive, desirable achievement has become both familiar and well established. Yet, anthropologists, of all people, are acutely aware that every culture has a form of education and training in important values and skills and a criteria for defining a person as knowledgeable, regardless of the degree of correspondence between these practices and a Western model of schooling (Levinson and Holland, 1996, p.2). In fact, some anthropologists have sided with a variety of social scientists, educators, and thinkers in critiquing the increasingly popular model of classroom schooling with Western-derived curricula. Recently, however, the complexity of social processes occurring under the roof of schools has taken front stage. Careful ethnographic studies have revealed active currents of contestation, negotiation and transformation of top-down policies, mainstream discourses and structures of power. Perhaps not surprisingly, children, families, teachers and communities display their agency through the development of personal and communal identities and aspirations. Nevertheless, questions about the power of the form and content of formal schooling on children and the cultures that they grow up to embody and enact remains of critical significance. That countries around the world have for the most part adopted similar schooling systems is beyond discussion. Today, “mass schooling removes children from families and local communities encouraging mastery of knowledges and disciplines that have currency and ideological grounding in wider spheres” (Levinson and Holland, 1996, p.1). The reasoning behind the widespread adoption of such a model of schooling lies in viewing education both as a human right and intrinsically connected to a nation’s economic development. Features of this global model include, with some variation, mass, compulsory, coeducational, classroom based schooling with standardized national curricula (AndersonLevitt, 2003, p.5). Behind an apparent global orchestration of schooling, however, is a diversity of reasons for the implementation of such parallel systems. Some countries, like the United States, England and France, have endogenously developed variations of the global model of schooling through a long history of political and economic changes (Industrial Revolution, universal suffrage, etc.). Meanwhile, developing countries have had to set up formal schooling schemes in an institutional and traditional vacuum under the directives of colonial governments or international economic organizations through development and monetary loan programs. Other countries, conscious of the discourse and paradigm of modernization and economic success emanating from the Western world have adopted the global model of education more or less willingly in order to pursue an elusive state of “progress”. Still, regardless of the country of focus, critics ranging from social theorists to educators to neo-colonial activists have spent much energy in their quest to debunk formal schooling from its unquestioned pedestal. Oftentimes termed the “great leveling mechanism” (Levinson and Holland, 1996, p.3), education has not contributed to social justice to the extent heralded by the social engineers of the West. In fact, the standardization of values and knowledge that the global model of schooling aims to achieve produces three outcomes, argue such thinkers. First, it is a tool of the nation-state to instill a national culture and identity on populations that may or may not be well integrated, beginning with the inculcation of official languages and nationalistic values. Second, it is instrumental in the subtle reproduction of certain social hierarchies, racial segregation and discrimination, and the proletarianization of the working class. Third, its focus on technical knowledge and work discipline achieves the quality and compliance of a workforce required for the functioning of modern economies. One of the foremost advocates of the role of the school in the social reproduction of inequality was Pierre Bourdieu, who together with Jean-Claude Passeron, published a study entitled, Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. In this book, Bourdieu expounded the idea that children of the working class reached school untrained in the values, skills, and behaviors transacted in middle and upper class social institutions. Thus “handicapped”, these children were easily labeled low achievers and developed a propensity for selfexclusion and self-limitation that resonated with their restricted objective opportunities. For Bourdieu, schooling replicated power relations, “naturalizing” them through a representation of education as a objective and meritocratic system and of culture as a natural, legitimate given (Jenkins, 1992, 105). This process of reproduction of socioeconomic inequalities he designated symbolic violence. A theory with powerful implications, Bourdieu’s idea of symbolic violence received widespread attention. Supporters confirmed through a variety of studies that indeed the school was a reproducer of social inequalities; in turn, critics advocated the view that educational social phenomena were much more complex than that portrayed by practice theorists. Accompanying a movement away from structuralism and towards the emerging postmodern paradigm, anthropologists approached the subject of education through ethnographic studies in schools, local communities and national policymaking circles. What they claimed to find was a diversity of experiences and results much beyond that pronounced by social critics, whose view of the “black box” of schooling essentially left the mechanisms of social reproduction unexplored and unexplained. For these researchers, schools provided “each generation with social and symbolic sites where new relations, new representations, and new knowledges can be formed, sometimes against, sometimes tangential to, sometimes coinciding with, the interests of those holding power” (Levinson and Holland, 1996, p.22). Overall the thrust was to shatter “the image of passive, malleable students implicit in reproduction theory” (p.9). Paul Willis’ 1977 study, Learning to Labour, remains to this day one of the key ethnographies in terms of demonstrating how social inequalities are reproduced, yet reproduced within a context of individual creativity, resistance, and identity formation. Observing a group of English working class “lads” in school, Willis recognized that their counter-school culture was an elaborate means of resisting mainstream cultural valuations and low possibility of social mobility. Through a framework of sexism and “strangled masculinity” these young men created for themselves a space of personal meaning, selfworth, and active decision-making. He states, “This study suggests…that there are deep disjunctions and desperate tensions within social and cultural reproduction. Social agents are not passive bearers of ideology, but active appropriators who reproduce existing structures only through struggle, contestation and a partial penetration of those structures” (Willis, 1977, p.175). In a sense Willis strongly challenged previous currents of social reproduction by striking an imaginary of determinism with a return to questions of agency and identity formation. For him the school is limiting, but also limited in its ability to impose ideologies and control people. A process of articulation of personal and institutional aims and complex negotiations amongst teachers, administrators, and students, formal schooling has paradoxical potentialities for the individual. Nevertheless, social, cultural and economic transformations affect much more than mere individuals—families and communities tangibly struggle to make sense of the form and content of state and private formal schooling and integrate it with respect to local culture, subsistence practices and values. S. Jungck and B. Kajornsin’s ethnographic study of Thai educational reform through the incorporation of traditional “Thai wisdom” into school curricula illustrates well this point. The authors describe how university-based teams spent between 6 to 18 months in communities to study local culture, jointly producing a curriculum with community members, teachers and policymakers based on indigenous knowledge and practices (Jungck and Kajornsin, 2003, p.40). While community members might have been expected to be pleased with this reform policy, many came to question the value and purpose of the new curriculum. According to the authors, local people implicitly wondered “if this was a curriculum of social reproduction when what they wanted was a curriculum of social mobility” (p.42). Revaluing local culture and traditions did not seem socially and economically empowering enough for villagers, yet this was one of the state’s highest educational reform policies. This case presents an ironic reversal of roles, where the state provides a locally-sourced curriculum while villagers question the expediency of honing cultural knowledge while rural villages languish economically. A third ethnographic case of significance is the study of state schools’ effects on Huaorani communities carried out by L. Rival in the 1990s. Here we learn that the state’s selfappointed mission to educate and modernize the Huaorani is met with approval by some Huaorani adults and children, who are interested in the imported, manufactured goods introduced by contact with the “modern” outside world. Yet “to teach Huaorani children the general skills of reading, writing, and counting requires not only their disembedding from the context of daily life, but more specifically, from the context of the forest and the longhouse”, asserts Rival (1996, p.157). The consequence of the school’s monopoly on children’s time is their de-skilling in regards to cultural and subsistence knowledge. Meanwhile, the school introduces social roles previously unknown to the Huaorani, such as the parent-child dichotomy, besides ushering in a work ethos coupled to a hierarchical social system incompatible with traditional egalitarianism. Overall, Rival’s assessment is that embedded in the “neutral” infrastructure of formal schooling are ontological and epistemological structures discordant with present-day Huaorani ones, a state of affairs that threatens the reproduction of Huaorani culture. Such ethnographic examples point to quite significant changes in our understanding of the role of schooling in social relations and the reproduction of socioeconomic structures. For many researchers, recognition of the profound discrepancy between education policy and discourses and the actual implementation and everyday, local schooling practices is the indispensable basis for the anthropology of education. In addition, conceptualizing schooling as the dialectics of transmission, acquisition and modification of knowledge serves to refocus the field on the study of learning, which has until recently been neglected in favor of teaching (Levinson et al., 2000, p.15-6). Yet if current anthropological questions center on the idea of individual agency, drawing on advances in social and developmental psychology as well as cognitive science may help us to achieve a better conception of how and what children learn in classrooms—how they negotiate between global and local cultural inputs and between personal, communal and national systems of values. Education, after all, is a major player in the dynamic process of identity formation. We cannot fail to acknowledge, on the other hand, that policymakers, teachers and administrators are not “guileless agents of the state, or handmaidens of the ruling class”, because they too are endowed with agency and in pursuit of personal moral, pedagogic and professional projects (Levinson et al., 2000, p.241; Willis, 1977, p.188). While the intricate indeterminacy of what happens inside schools around the globe has been well established, to recognize the more frequent ways in which children are affected in emotional, cognitive, social and economic terms by local and global models of education remains fundamental. For all attempts at negotiation and personal autonomy, students’ development of a sense of self-worth, possibility and potentiality—a shaping of habitus that has long-term consequences—is what truly lies on the line. Moreover, global political and economic structures, in the end, remain powerful constrainers of objective economic possibilities and social mobility. In particular, given the characteristically narrow requirements of national labor markets, it is not only the form of schooling but also its content and the quality of teaching that matters for children’s future employment opportunities. Both technical knowledge and social capital continue to be crucial factors in empowering individuals to negotiate a better place in social hierarchies. In whatever ways schooling may diverge in global settings, the painful reality is that social outcomes continue to converge—inequality is being successfully reproduced. The question of educational reform movements, a topic beyond the scope of this essay, remains at the heart of the anthropology of education. It suffices to say that divergent models exist there as well—towards more efficient and effective systems of Western schooling or towards alternative, decentralized, humanistic models of education. The bottom line seems to be that much care and reflection must be paid to what goes on during the time and in spaces where children, teenagers and young adults spend most of their years. Bibliography Anderson-Levitt, K. 2003. “A World Culture of Scholing?” In Local Meanings, Global Schooling. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Bourdieu, P. and J. Passeron. 1990. Reproduction, Education and Culture. Sage. Eisenhart, M., 2000. “New Directions in the Study of Culture, Learning, and Education”. In Schooling the Symbolic Animal. Levinson, B. and D. Holland (eds.) Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. Jenkins, R. 1992. Pierre Bourdieu. Oxford: Routledge. Jungck, S. and B. Kajornsin. 2003. “ ‘Thai Wisdom’ and GloCalization: Negotiating the Global and the Local in Thailand’s National Educational Reform”. In Local Meanings, Global Schooling. Anderson-Levitt, K. (ed.) New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Levinson, B. and D. Holland. 1996. “The Cultural Production of the Educated Person: An Introduction”. In The Cultural Production of the Educated Person. Levinson, B., D. Foley and D. Holland (eds.). Albany: State University of New York Press. Levinson, B. et al. 2000. Schooling the Symbolic Animal. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. Reed-Danahay, Deborah. 1987. “Farm Children at School: Educational Strategies in Rural France”, Anthropological Quarterly. 60(2):83-89. Rival, L. 1996. “Formal schooling and the production of the modern citizen in the Ecuadorian Amazon”. In The Cultural Production of the Educated Person. Levinson, B., D. Foley and D. Holland (eds.). Albany: State University of New York Press.