Document

advertisement

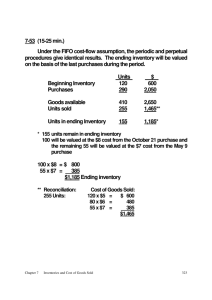

CHAPTER 19 REPORTING INVENTORY 1 Chapter Overview How does a company determine the costs and amounts of inventory that it includes in the inventory reported on its balance sheet? What alternative cost flow assumptions may a company use for determining its cost of goods sold and ending inventory? How do alternative cost flow assumptions affect a company’s financial statements? 2 Chapter Overview How do a company’s inventory and cost of goods sold disclosures help a user evaluate the company? How does a company apply the lower-ofcost-or-market method to report the inventory on its balance sheet? What methods may a company use to estimate its cost of goods sold and inventory? 3 Reporting Inventory on the Balance Sheet A company using GAAP is required to base its inventory reporting on two accounting concepts we discussed in earlier chapters: historical cost and matching. Historical cost states that a company records its transactions on the basis of the dollars exchanged; in other words, the cost of the inventory purchased. Historical cost provides the most reliable value and the most conservative value for inventory, reflecting GAAP’s emphasis on conservatism. 4 Reporting Inventory on the Balance Sheet The matching principle states that the cost of producing revenues for an accounting period must be deducted from the revenue earned. Therefore, a company reports inventory expense, known as cost of goods sold, in the period in which it sells inventory and reports the revenue from the sale. Inventory is one of the most ideal illustration of how the GAAP matching principle is applied. 5 Computing Historical Cost The cost of each unit of inventory includes all of the cost incurred to bring the item to its existing condition and location. Cost includes the purchase price (less purchase discounts), sales tax, applicable transportation costs, insurance, custom duties and similar costs. A company determines the cost of each unit of inventory by reviewing the source documents (i.e., invoices) used to record the purchase. 6 Goods In Transit When a company takes a physical inventory, the purpose is to determine the total cost of goods on hand at the end of the accounting period. Goods may be in transit at this time, both from suppliers and to customers. A company can buy or sell inventory using FOB shipping point or FOB destination terms. Economic control transfers at the same time legal ownership transfer. 7 Goods In Transit: FOB Shipping Point FOB shipping point means that the title to the goods transfers when the inventory is delivered to the shipping agent. If a company purchases goods with these terms, then title transfers when shipped. A company must include the cost of the inventory in the yearend count even though it may not have physically arrived. If goods are being sold with these terms, then title transfers to the customer when shipped. A company must exclude the cost of the inventory in the year-end count even though it may not have physically arrived at the customer’s location. 8 Goods In Transit: FOB Destination FOB destination means that the title to the goods transfers when the inventory arrives at the place of delivery. If a company purchases goods with these terms, then title transfers when they arrive. A company must exclude the cost of the inventory in the yearend count if it has not physically arrived. If goods are being sold with these terms, then title transfers to the customer when delivered. A company must include the cost of the inventory in the year-end count if it has not yet arrived at the customer’s location. 9 Inventory Cost Flow Assumptions Once a company has determined the number of units in its ending inventory and the cost of the units it purchased during the period, it must determine how to allocate the total cost of these units between the ending inventory and the balance sheet: Cost of Beginning Inventory = + Cost of Purchases* Cost Goods Available for Sale *or Cost of Goods Manufactured Balance Sheet Cost of Ending Inventory = + Cost of Goods Sold Income Statement 10 Inventory Cost Flow Assumptions If the cost of each unit of inventory is the same during the period, a company simply allocates these costs between inventory and cost of goods sold according to how many units it has left and how many were sold. Most of the time, costs in the inventory are at various amounts and it becomes more difficult to determine which costs a company includes in cost of goods sold and which are included in the ending inventory. 11 Inventory Cost Flow Assumptions GAAP allows a company to choose one of four alternative cost flow assumptions to allocate its cost of goods available for sale between ending inventory and cost of goods sold. 1. Specific identification 2. First-in, First-out (FIFO) 3. Average Cost, and 4. Last-in, First-out (LIFO) 12 Granola Goodies Company: Inventory Information: FIFO Calculation FIFO Ending Inventory (Perpetual Inventory System): 200 units @$5.50/unit (from January 12 purchase) $ 1,100 900 units @$6.00/unit (from January 24 purchase) $ 5,400 $ 6,500 First goods in are the first goods out 13 Granola Goodies Company: Inventory Information: LIFO Calculation LIFO Ending Inventory (Perpetual Inventory System): 700 units @$6.00/unit (from January 24 purchase) $ 4,200 400 units @$5.00/unit (from beginning inventory) $ 2,000 $ 6,200 Last goods in are the first goods out 14 Effect of FIFO and LIFO on the Financial Statements The choice made to adopt FIFO or LIFO affects both the balance sheet and the income statement. FIFO FIFO $ 16,900 LIFO LIFO $ 16,900 Sales Cost of goods available for sale $ 13,150 $ 13,150 Ending inventory $ (6,500) $ (6,200) Cost of goods sold $ (6,650) $ (6,950) Gross profit $ 10,250 $ 9,950 When costs are rising, cost of goods sold will be lower under FIFO because the first cost moved into cost of goods sold are the earlier (lower) costs. Gross profit, net income and ending inventory are higher. When costs are rising, cost of goods sold will be higher under LIFO because the first cost moved into cost of goods sold are the later (higher) costs. Gross profit, net income, and ending inventory are lower. 15 Income Measurement Issues LIFO may seem counter-intuitive – it assumes an illogical cost flow that results in lower gross profit, net income and an ending inventory valuation on the balance sheet. Why would a company use this? Many users of financial statement argue that LIFO presents a more accurate picture of profitability when costs are rising because it matches current costs with revenues. While FIFO results in higher profits, an argument against this method is that it creates artificial profits from holding inventory at historical costs which is less than its current replacement value. 16 Impact of Tax Rules In general, a company is not bound to use the same accounting method for tax purposes that is used for financial reporting purposes. There are many difference between financial reporting and tax basis profits and inventory is among them, except when it comes to LIFO. LIFO is an attractive choice for tax purposes because lower financial profits produce lower taxes. Lower taxes result in less cash outflow. 17 Impact of Tax Rules However, to use LIFO for tax purposes, a company must have “book/tax conformity.” This means that LIFO must be used for financial reporting purposes as well as for tax purposes. The cash deferral from tax savings is usually very significant and is sufficient for many companies to choose LIFO for financial reporting purposes. For instance, ExxonMobil, General Motors, and General Electric together have saved over $3 billion in taxes by using LIFO instead of FIFO. 18 Choosing a Cost Flow Method If managers of a company expect that the costs of inventory will increase in the future, then we should expect them to select LIFO because of the lower taxes that the company will have to pay. Reporting lower net income, however, does not mean the the company’s stock price goes down. Since cash is being saved and the company is matching current revenues and costs, it is more likely that investors will favorably react to the adoption of LIFO. 19 Choosing a Cost Flow Method Regardless of the method chosen, once a company selects a method, GAAP requires that it be applied consistently from period to period. A company can’t choose LIFO one year and FIFO the next. A company can change is method of cost-flow assumption but there must be a valid underlying reasons for the change. GAAP requires that the effect of the change be highlighted and explained in a company’s annual report. 20 Financial Statement Disclosure When inventory is paid for, it reduces operating cash flows on the statement of cash flows. Cost of goods sold is deducted from net sales to arrive at gross profit on the income statement. A company must disclose its inventory cost flow assumption, method of inventory valuation, and components of inventory (if a manufacturer). Inventory is usually reported right after receivables, in order of liquidity. 21 Lower of Cost or Market Valuation The GAAP requirement that companies report inventories at historical cost (under one of the cost-flow assumptions) is modified in one situation. When the market value of a company’s inventory falls below its cost, the company is required to reduce, or “write down” the inventory to market value. This rule is called the lower-of-cost-or-market (LCM) method. 22 Lower of Cost or Market Valuation For the LCM rule, market value means replacement value of the inventory, not selling price. Assume Cane Candy Corporation has 100 boxes of Candy for which it paid $50 a box but the replacement cost is $40 per box. What must the company do? Under the LCM rule, the company writes down the inventory $10 per box (taking a loss on its income statement) and reports the value of the inventory at $40 on the balance sheet. 23 Lower of Cost or Market Valuation The LCM rule is a good example of how the concept of conservatism is applied in GAAP. The conservatism principle states that a company should apply GAAP in a way that there is little chance that it will overstate assets or income. Therefore, companies record losses when evidence of loss exists but only record gains when they arise as a result of transactions. Conservatism does not mean that a company can intentionally understates assets or revenues. 24 Lower of Cost or Market Valuation While conservatism may bias reporting, the rational for the LCM rule makes sense if one thinks about the marketplace. If a company can replace its current inventory by paying a lower amount, then it is equally as likely that the price at which it ultimately sells the merchandise to customers will also be less. This is further validated by the fact that there is usually a constant relationship between selling price and cost in companies. 25 Inventory Estimation Methods Sometimes a company needs to estimate the cost of its inventory. If there is a fire or theft, or if records are destroyed, it may need to estimate its loss. Also, if a company uses the periodic inventory method, estimation methods can be used at interim reporting periods without incurring the cost or time of a physical inventory. Companies use the gross profit method for the reasons set forth above, whereas retail merchandisers routinely use the retail inventory method for financial reporting. 26 Gross Profit Method Assume the following information: Beginning inventory for Watson Company is $12,000, net purchases are $48,000, and net sales are $70,000. The historic rate of gross profit is 40%. Using this information, we can estimate the company’s ending inventory using four steps. 27 Gross Profit Method: Step 1 The first step is to estimate the current gross profit based on the historical information. Estimated Gross Profit (Estimated GP) = Net Sales X Historical Gross Profit Percentage (GP%). $70,000 X 40% = $28,000 Net Sales X G.P. % = Estimated GP 28 Gross Profit Method: Step 2 The second step is to determine the cost of goods sold. Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) = Net Sales Gross Profit (GP). $70,000 - $28,000 Net Sales - G.P. = $42,000 = COGS 29 Gross Profit Method: Step 3 The third step is to determine the actual cost of goods available for sale. Cost of Goods Available for Sale (COGAS ) = Beginning Inventory (Beg. Inv.) + Net Purchases (NP). $12,000 + $48,000 = $60,000 Beg. Inv. + NP = COGAS 30 Gross Profit Method: Step 4 The fourth and last step is to estimate the ending inventory. Ending Inventory (End. Inv.) = Cost of Goods Available for Sale (COGAS) – Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) $60,000 - $42,000 = $18,000 COGAS - COGS = End. Inv. 31 Summary of Gross Profit Relationships We can illustrate the results of steps 1- 4 using the starting information and the information calculating through the four gross profit estimation steps: Net sales Cost of goods sold: Step 3: Cost of Beginning inventory goods available $ for sale calculated Net purchases $ Cost of goods available for sale (3) $ Less. Ending inventory (estimated) (4) $ Cost of goods sold Step 1: gross Gross Profit (estimated) profit calculated Step 4: Ending inventory estimated $ 70,000 100% 12,000 Step 2: Cost 48,000 of goods sold calculated 60,000 (18,000) (2) $ (42,000) 60% (1) $ 28,000 40% 32 Retail Inventory Method Retail companies find it easier and less expensive to based their inventory accounting system on the retail value of their inventory. The main reason for this is that the inventory is marked and on display at the retail price. During the physical inventory, it is easier to count the inventory at retail prices than to go back and identify the cost of every item. 33 Retail Inventory Method – Step 1 A company calculates its ending inventory based on a cost-to-retail ratio using four steps. The first step is to compute the total goods available for sale at both cost and retail prices. Beginning inventory Purchases (net) Goods available for sale Cost Retail $ 12,000 $ 20,000 $ 48,000 $ 80,000 $ 60,000 $ 100,000 (1) 34 Retail Inventory Method – Step 2 The second step is to compute a cost-toretail ratio by dividing the cost of goods available for sale by the retail value of the goods available for sale. Beginning inventory Purchases (net) Goods available for sale Cost-to-retail ratio: Cost Retail $ 12,000 $ 20,000 $ 48,000 $ 80,000 $ 60,000 $ 100,000 (1) $60,000 = 60% $100,000 (2) 35 Retail Inventory Method – Step 3 The third step is to compute the ending inventory at retail by subtracting the net sales for the period from the retail value of the goods available for sale. Beginning inventory Purchases (net) Goods available for sale Cost-to-retail ratio: Cost Retail $ 12,000 $ 20,000 $ 48,000 $ 80,000 $ 60,000 $ 100,000 (1) $60,000 = 60% $100,000 Less: Sales (net) Ending inventory at retail (2) $ (70,000) (3) $30,000 36 Retail Inventory Method – Step 4 The fourth and last step is to compute the ending inventory at cost by multiplying the ending inventory at retail by the cost-to-retail ratio. Cost Retail $ 12,000 $ 20,000 $ 48,000 $ 80,000 $ 60,000 $ 100,000 (1) Beginning inventory Purchases (net) Goods available for sale Cost-to-retail ratio: $60,000 $100,000 = 0.60 (2) Less: Sales (net) $ (70,000) (3) Ending inventory at retail $30,000 Ending inventory at cost (0.60 X $30,000) $18,000 (4) 37