File

advertisement

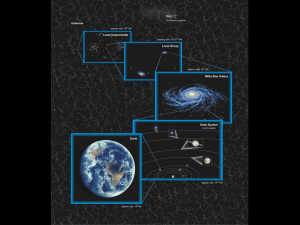

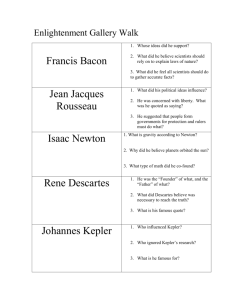

Tayler Vence PHYS 1010 5/5/2013 The Copernican Revolution The story of Copernican Revolution is one of the many examples of a shift in the way we view the world, and also a large shift for the realm of physical science. This being said, it is important to recap the features and views of the pre-revolution. The comparisons between what happened then and now will demonstrate surprising new ideals current day and realities that have far-reaching repeals for science and religion. Five hundred years ago, as the Middle Ages came to close and the Renaissance was at its early dawn, it was widely believed that human beings played a “pre-eminent role” in the universe and on Earth; everything was believed to revolve around man, both physically and in religious aspect. The Old Testament story of Genesis was known not as a theory but as a historical fact. It was also known that God had created the Earth and the Heavens and that humanity was the focus of God and of religion as a whole. The model of the solar system developed by the Greek philosopher Ptolemy around 140 AD was still standing strong. This model showed that the sun, moon, and all the planets and stars all revolved around the earth in circular orbits. Back then everyone believed that the Earth stood still at the center of the universe (Miller, Keating, Sidhwa). It was, however, recognized that there were problems with this model, making inaccurate, but at the time how to correct this model was unknown. The biggest problem with this model was that the stars move smoothly through the heavens along fixed circular orbits, but the planets do not; they orbit around the other stars. Their speed varies, their orbits are not perfect, and they can even occasionally reverse their orbital direction. At that time it was believed that planetary motion must be based on circles. Plato had argued that heavenly bodies were governed by a different set of physical laws than those that governed the Earth. Plato continually argued that because these Heavenly bodies were “perfect” their orbit must also be “perfect.” According to Plato, the perfect motion was circular motion (Plato). How is it possible to accurately explain the wobbly and elliptical orbits of these planets as perfectly circular? The best solution astronomers could offer was the proposition of a system of epicycles. An Epicycle is defined as a circle in which a planet moves and which has a center that is itself carried around at the same time on the circumference of a larger circle. So if the planets moved around small circles that they themselves rolled along the larger circular orbits then this could explain some of the strange planetary motions. (Coffey) As time passed and it was possible to collect more accurate data, it became apparent that simple epicycles could not account for all of the irregularities in the planetary motions. In response to this many medieval astronomers proposed more complex epicycles. In these new epicycles circles moved along circles that were moving along other circles. As these epicycle theories continued to be disproved, physicists and astronomers would further complicate this pattern adding various oscillations and orbits making them even more complex than they had already been. (Coffey) This view of the galaxy and the universe survived unchallenged by any astronomer or physicist for over thirteen hundred years. In the early 16th century, it was finally challenged by the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus. Copernicus defied this known model of the universe with his Heliocentric model – which showed that the Earth revolves around the sun, and is not the center of the universe. Copernicus suggested that the reason the stars appeared to orbit the Earth was because the Earth itself was moving, revolving upon its own axis in intervals of 24 hours (a day’s length). Suggesting that the Earth moved was seen as Heresy to the Catholic Church and as well to the bible; however, Copernicus continually argued that the odd “wandering” motion of the known planets could also be explained if they were orbiting the Sun, instead of the Earth. This led to the theory that the Earth was also in orbit around the sun. (Cessna) Copernicus had known the views of the church and how they regard the Earth as the center of the universe due to its importance in the bible; however, this did not stop him from proposing it is incorrect. In proposing this theory, Copernicus was not only challenging orthodox science; he was also challenging the way the religious and societal world viewed reality as they knew it. It is because of this fear of the wrath of the church and also the wrath of society that he did not disclose these ideas to the public for thirty whole years. It was not until Copernicus was near death that he shared this knowledge with the world in fear of taking this philosophy that could very well be the truth to the grave. In 1543 Copernicus finally decided to publish his book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres). When the book was published it was immediately placed on the papal index of forbidden books as seen fit by the Catholic Church. Copernicus also saw the first copy of the publication on the same day that he died. The book was hardly even touched or looked over for the next eighty years, until the Italian scientist Galileo Galilei took up an interest in planetary motions. With the utilization of the telescope (which was newly invented), he found convincing evidence that gave credibility to the Copernican model of Heliocentrism. He noted that Venus had phases that were similar to the moon’s phases, when only half, or just a crescent, of it would be lit – this is exactly what should happen if Venus orbited the Sun, and not the Earth. Galileo also discovered that Jupiter had its own moons in its planetary orbit; this disproved the idea that everything revolved around the Earth almost instantaneously. Not long after the publication of his findings Galileo was contacted by the Catholic Church and it was demanded that he put a cease to his heretical ideas. Sadly enough, Galileo did in fact stop his studies in fear for his life. However, after a few years, Galileo could no longer stand to hold a truth so important from the public, thus he published Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems in which he defended and supported the Copernican theory. Again, under threat of torture, he was forced to throw out the absurd view that the Earth moves around the sun. He was then put under house arrest so that he could be watched and prevented from causing any more trouble to the Catholic Church. Sadly he remained under house arrest until the day he died. (Machamer) During the same time Galileo was discerning his observations of the planets, a German mathematician by the name Johannes Kepler, was putting into place another key piece of the puzzle of the universe. Copernicus had argued that the Sun, not the Earth, was at the center of things, but he still believed in the theory of circular motion, and although his model explained planetary movements much better than the old geocentric model, there were still unexplained phenomena, which Copernicus had tried to account for with the theory of epicycles. Kepler was the student of the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, who had collected and studied various volumes of accurate astronomical observations. Brahe set Kepler to work on the motion of Mars, the planet with the most irregular orbit according to the geocentric model. Kepler’s breakthrough was the discovery that the movements of Mars, and all the other planets, could be accounted for without any need for epicycles, if their orbits were ellipses rather than circles. This in turn disproves the theory of perfect circular motion. (NASA) The final piece of the puzzle regarding the Copernican Theory would be put in place some 50 years later by none other than the English mathematician, Sir Isaac Newton. Newton came to the realization that heavenly bodies were governed by the exact same laws as Earthly objects (in opposition to the geocentric theory); the force that causes an apple to fall is the same force that holds the moon in its orbit around the Earth –gravity. After working with equations of motion he discovered that orbiting bodies would indeed move in ellipses. This ties together with Kepler’s discoveries and theories. (Hatch) It is with these discoveries that the Copernican Revolution would come to a close and be accepted as scientifically correct (although the Vatican would not accept this as correct until 1992). This time stretching discovery had worked its way up through many years of breakthroughs in science as well as technology from Copernicus and took nearly 150 years to complete. Artifacts: This particular artifact is the Copernican model of Heliocentrism taken from Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium. It is a simple diagram of his theory that the Earth NOT the center of the galaxy and that it is in fact the Sun that is at the center, with the planets in orbit of the Sun. This artifact is the Geocentric model of the solar system as Aristotle believed to be correct. It is a diagram of the solar system with the Earth at the center and all the other planets and the Sun revolving around it. This is a diagram explaining the “epicycles” of the planets’ and Sun’s orbit about the Earth in regards to Geocentrism Works Cited Cessna, Abby. "Heliocentric Model." Universe Today RSS. Universe Today, 22 June 2009. Web. 05 May 2013. Coffey, Jerry. "Epicycles." Universe Today RSS. Universe Today, 31 Mar. 2010. Web. 05 May 2013. Hatch, Robert A. "Isaac Newton Biography - Newton's Life, Career, Work - Dr Robert A. Hatch." Isaac Newton Biography - Newton's Life, Career, Work - Dr Robert A. Hatch. University of Florida, Jan. 2002. Web. 05 May 2013. "Kepler: Johannes Kepler." Kepler: Johannes Kepler. NASA, n.d. Web. 05 May 2013. Machamer, Peter. "Galileo Galilei." Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, 2012. Web. 05 May 2013. Miller, Patrick, Christopher Keating, and Anahita Sidhwa. "The Center of the Galaxy." Solar System Exploration. NASA / Audentes Publishing Co., 21 Feb. 2011. Web. 05 May 2013. Plato. "Timaeus - Plato." Timaeus - Plato. Trans. Benjamin Jowett. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 May 2013. .