The New Tycoons: Andrew Carnegie

advertisement

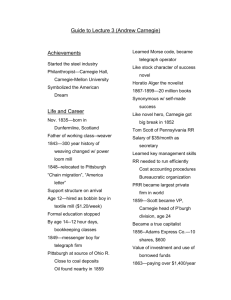

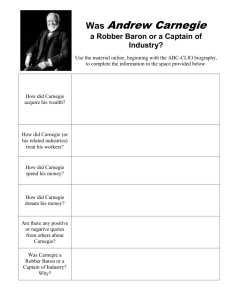

The New Tycoons: Andrew Carnegie By the time he died in 1919, Carnegie had given away $350,695,653. At his death, the last $30,000,000 was likewise given away to foundations, charities and to pensioners. Oil was not the only commodity in great demand during the Gilded Age. The nation also needed steel. The railroads needed STEEL for their rails and cars, the navy needed steel for its new naval fleet, and cities needed steel to build skyscrapers. Every factory in America needed steel for their physical plant and machinery. Andrew Carnegie saw this demand and seized the moment. Humble Roots Like John Rockefeller, ANDREW CARNEGIE was not born into wealth. When he was 13, his family came to the United States from Scotland and settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, a small town near Pittsburgh. His first job was in a cotton mill, where he earned $1.20 per week. His talents were soon recognized and Carnegie found himself promoted to the bookkeeping side of the business. An avid reader, Carnegie spent his Saturdays in the homes of wealthy citizens who were gracious enough to allow him access to their private libraries. After becoming a telegrapher for a short while, he met the head of a railroad company who asked his services as a personal secretary. Millionaire Andrew Carnegie spoke against irresponsibility of the wealthy and sharply criticized ostentatious living. During the Civil War, this man, THOMAS SCOTT, was sent to Washington to operate transportation for the Union Army. Carnegie spent his war days helping the soldiers get where they needed to be and by helping the wounded get to hospitals. By this time, he had amassed a small sum of money, which he quickly invested. Soon iron and steel caught his attention, and he was on his way to creating the largest steel company in the world. Vertical Integration: Moving on Up The Besse When WILLIAM KELLY and HENRY BESSEMER perfected a process to convert iron to steel cheaply and efficiently, the industry was soon to blossom. Carnegie became a tycoon because of shrewd business tactics. Rockefeller often bought other oil companies to eliminate competition. This is a process known as HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION. Carnegie also created a VERTICAL COMBINATION, an idea first implemented by GUSTAVUS SWIFT. He bought railroad companies and iron mines. If he owned the rails and the mines, he could reduce his costs and produce cheaper steel. Carnegie was a good judge of talent. His assistant, HENRY CLAY FRICK, helped manage the CARNEGIE STEEL COMPANY on its way to success. Carnegie also wanted productive workers. He wanted them to feel that they had a vested interest in company prosperity so he initiated a profit-sharing plan. All these tactics made the Carnegie Steel Company a multimillion dollar corporation. In 1901, he sold his interests to J.P. Morgan, who paid him 500 million dollars to create U.S. Steel. Giving Back Retirement did not take him out of the public sphere. Before his death he donated more than $350 million dollars to public foundations. Remembering the difficulty of finding suitable books as a youth, he helped build three thousand libraries. He built schools such as CARNEGIE-MELLON UNIVERSITY and gave his money for artistic pursuits such as CARNEGIE HALL in New York. Andrew Carnegie was also dedicated to peace initiatives throughout the world because of his passionate hatred for war. Like Rockefeller, critics labeled him a robber baron who could have used his vast fortunes to increase the wages of his employees. Carnegie believed that such spending was wasteful and temporary, but foundations would last forever. Regardless, he helped build an empire that led the United States to world power status. The New Tycoons: Andrew Carnegie. U.S. History: Pre-Columbian to the New Millenium, 15 Oct, 2013. http://www.ushistory.org/us/36c.asp Growth and transformation: The United States in the Gilded Age From Outline of U.S. History. Provided by U.S. Department of State. The Ohio Works of the Carnegie Steel Company in Youngstown, Ohio, 1910. Click to see the full panoramic photograph. (Haines Photo Co. More about the photograph) Between two great wars – the Civil War and the First World War – the United States of America came of age. In a period of less than 50 years it was transformed from a rural republic to an urban nation. The frontier vanished. Great factories and steel mills, transcontinental railroad lines, flourishing cities, and vast agricultural holdings marked the land. With this economic growth and affluence came corresponding problems. Nationwide, a few businesses came to dominate whole industries, either independently or in combination with others. Working conditions were often poor. Cities grew so quickly they could not properly house or govern their growing populations. Technology and change “The Civil War,” says one writer, “cut a wide gash through the history of the country; it dramatized in a stroke the changes that had begun to take place during the preceding 20 or 30 years.…” War needs had enormously stimulated manufacturing, speeding an economic process based on the exploitation of iron, steam, and electric power, as well as the forward march of science and invention. In the years before 1860, 36,000 patents were granted; in the next 30 years, 440,000 patents were issued, and in the first quarter of the 20th century, the number reached nearly a million. As early as 1844, Samuel F. B. Morse had perfected electrical telegraphy; soon afterward distant parts of the continent were linked by a network of poles and wires. In 1876 Alexander Graham Bell exhibited a telephone instrument; within half a century, 16 million telephones would quicken the social and economic life of the nation. The growth of business was speeded by the invention of the typewriter in 1867, the adding machine in 1888, and the cash register in 1897. The linotype composing machine, invented in 1886, and rotary press and paper-folding machinery made it possible to print 240,000 eight-page newspapers in an hour. Thomas Edison’s incandescent lamp eventually lit millions of homes. The talking machine, or phonograph, was perfected by Edison, who, in conjunction with George Eastman, also helped develop the motion picture. These and many other applications of science and ingenuity resulted in a new level of productivity in almost every field. Concurrently, the nation’s basic industry – iron and steel – forged ahead, protected by a high tariff. The iron industry moved westward as geologists discovered new ore deposits, notably the great Mesabi range at the head of Lake Superior, which became one of the largest producers in the world. Easy and cheap to mine, remarkably free of chemical impurities, Mesabi ore could be processed into steel of superior quality at about one‑ tenth the previously prevailing cost. Carnegie and the age of steel Andrew Carnegie was largely responsible for the great advances in steel production. Carnegie, who came to America from Scotland as a child of 12, progressed from bobbin boy in a cotton factory to a job in a telegraph office, then to one on the Pennsylvania Railroad. Before he was 30 years old he had made shrewd and farsighted investments, which by 1865 were concentrated in iron. Within a few years, he had organized or had stock in companies making iron bridges, rails, and locomotives. Ten years later, he built the nation’s largest steel mill on the Monongahela River in Pennsylvania. He acquired control not only of new mills, but also of coke and coal properties, iron ore from Lake Superior, a fleet of steamers on the Great Lakes, a port town on Lake Erie, and a connecting railroad. His business, allied with a dozen others, commanded favorable terms from railroads and shipping lines. Nothing comparable in industrial growth had ever been seen in America before. Though Carnegie long dominated the industry, he never achieved a complete monopoly over the natural resources, transportation, and industrial plants involved in the making of steel. In the 1890s, new companies challenged his preeminence. He would be persuaded to merge his holdings into a new corporation that would embrace most of the important iron and steel properties in the nation. Corporations and cities The United States Steel Corporation, which resulted from this merger in 1901, illustrated a process under way for 30 years: the combination of independent industrial enterprises into federated or centralized companies. Started during the Civil War, the trend gathered momentum after the 1870s, as businessmen began to fear that overproduction would lead to declining prices and falling profits. They realized that if they could control both production and markets, they could bring competing firms into a single organization. The “corporation” and the “trust” were developed to achieve these ends. Corporations, making available a deep reservoir of capital (money and other assets) and giving business enterprises permanent life and continuity of control, attracted investors both by their anticipated profits and by their limited liability in case of business failure. The trusts were in effect combinations of corporations whereby the stockholders of each placed stocks in the hands of trustees. (The “trust” as a method of corporate consolidation soon gave way to the holding company, but the term stuck.) Trusts made possible largescale combinations, centralized control and administration, and the pooling of patents. Their larger capital resources provided power to expand, to compete with foreign business organizations, and to drive hard bargains with labor, which was beginning to organize effectively. They could also exact favorable terms from railroads and exercise influence in politics. ExplorePAhistory.com Name: Andrew Carnegie [Steel] Region: Pittsburgh Region County: Allegheny Marker Location: Carnegie Library, 4400 Forbes Ave., Pittsburgh Dedication Date: April 18, 1996 Behind the Marker Andrew Carnegie, circa 1896. Andrew Carnegie was a singular figure in American history. The "rags to riches" ideal celebrated in the Horatio Alger stories was mostly a myth: rags most often led to rags, or at best a modest prosperity, while rich people most often had rich parents. But Carnegie actually lived it. Born a poor immigrant boy, he became the "richest man in the world." Andrew Carnegie was born on November 25, 1835, in Dunfermline, Scotland, the eldest son of a handloom weaver. The family left Scotland in 1848, in economic straits, and followed a chain of Scottish immigrants to Pittsburgh. Later in life, when he returned as a latter-day laird to Skibo Castle, Carnegie would revel in his Scottish heritage and upbringing. Yet even in Pittsburgh as a young man, a network of Scottish immigrants steered him to jobs in a textile factory and telegraph office. The Edgar Thomson Steel Works, by William Rau, Braddock, PA, 1891. At age eighteen, Carnegie became special assistant for Tom Scott, who had recently become western superintendent for the Pennsylvania Railroad. From Scott he mastered the details of running trains through Pennsylvania's mountains and the principles of modern management. A classic "inside investor," Carnegie made easy profits in such railroadrelated ventures as bridge building, railroad sleeping cars, telegraphs, and iron and steel mills. In the 1870s, Carnegie named his flagship steel mill after the Pennsylvania's president, J. Edgar Thomson. Carnegie's first sizable fortune came in selling bonds for these many varied business ventures to European investors. Carnegie's second, much larger fortune flowed from his adage to "put all your eggs in one basket, then watch it carefully." This basket, of course, was steel. Carnegie bought his first iron furnaces and rolling mills, including Freedom Iron as an offshoot of his railroad ventures in the 1860s. After the Edgar Thomson mill, opened in 1875, he focused on creating an empire in steel. To undersell competitors in good times and bad, Carnegie cut costs obsessively and made massive investments in technology. Facsimile Bill of Sale, Andrew Carnegie's sale of the Carnegie Company and all... An association with Henry Clay Frick in the 1880s gave Carnegie's mills control over the coke that fueled his mills. As his fame grew with his fortune, Carnegie launched a "literary" career with celebrated essays on the gospel of wealth and on the labor question, the latter of which attracted a storm of criticism following the violent Homestead strike of 1892. When financier J. P. Morgan put together U. S. Steel in 1901 to eliminate Carnegie's relentless competitiveness, Carnegie's mills, railroads, coke lands, and iron ore holdings formed the centerpiece of the nation's first billion-dollar corporation. Morgan paid $480 million for Carnegie Steel, of which Carnegie's personal share was $225,639,000. Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Carnegie say farewell to Pittsburgh, 1914. Giving away this huge sum of money - the equivalent in 2004 of about $120 billion, approximately twice Bill Gate's fortune - proved more difficult than Carnegie had imagined. In his celebrated "Gospel of Wealth" Carnegie stated, "The man who dies rich, dies disgraced." In 1881 he gave money for constructing a library in his birthplace in Scotland, and then for a dozen or so libraries in the United States, beginning in Braddock. (Carnegie typically paid only for the library building and required the town to buy books and pay for upkeep, except in the four cases of Braddock, Homestead, Duquesne and his namesakesuburb of Pittsburgh where he paid for the whole show.) Carnegie's philanthropy did not win universal approval. Many workers accused Carnegie of using charity to mask the corporate greed that had robbed them of the money produced by their toil. When handling the paperwork became a burden, Carnegie set up a half dozen foundations that funded 2,811 public libraries, 7,689 church organs, numerous educational ventures, and countless pensions for public figures, peacetime heroes, and college faculty. Still, interest on his fortune accumulated almost as fast as he could give it away. In 1911, with a massive gift of $125 million, he created the Carnegie Corporation of New York for "the advancement and diffusion of knowledge." The noble cause of promoting international peace, not an easy task during World War I, occupied his remaining years. He died on August 11, 1919, having successfully given away $380 million, his entire fortune. http://www.sjusd.org/leland/teachers/sgillis/immigration/pdf/1st_wave_summar y.pdf 1st wave migration patterns : Who were they and where did they come from: Western and Northern Europe IRISH At the beginning of the 19th century the dominant industry of Ireland was agriculture. Large areas of this land was under the control of landowners living in England. Much of this land was rented to small farmers who, because of a lack of capital, farmed with antiquated [old] implements and used backward methods. The average wage for farm laborers in Ireland was eight pence a day. This was only a fifth of what could be obtained in the United States and those without land began to seriously consider emigrating to the New World. In 1816 around 6,000 Irish people sailed for America. Within two years this figure had doubled. Early arrivals were recruited to build canals. In 1818 over 3,000 Irish labourers were employed on the Erie Canal. By 1826 around 5,000 were working on four separate canal projects. One journalist commented: "There are several kinds of power working at the fabric of the republic - water-power, steam-power and Irish-power. The last works hardest of all." In October 1845 a serious blight began among the Irish potatoes, ruining about three- quarters of the country's crop. This was a disaster as over four million people in Ireland depended on the potato as their chief food. The blight returned in 1846 and over the next year an estimated 350,000 people died of starvation and an outbreak of typhus that ravaged a weaken population. Despite good potato crops over the next four years, people continued to die and in 1851 the Census Commissioners estimated that nearly a million people had died during the Irish Famine. The British administration and absentee landlords were blamed for this catastrophe by the Irish people. The Irish Famine stimulated a desire to emigrate. The figures for this period show a dramatic increase in Irish people arriving in the United States: 92,484 in 1846, 196,224 in 1847, 173,744 in 1848, 204,771 in 1849, and 206,041 in 1850. By the end of 1854 nearly two million people - about a quarter of the population - had emigrated to the United States in ten years. A census carried out in 1850 revealed that there were 961,719 people in the United States that had been born in Ireland. At this time they mainly lived in New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Illinois, Ohio and New Jersey. The Irish Emigrant Society tried to persuade immigrants to move to the interior but the vast majority were poverty-stricken and had no money for transport or to buy land. … Thousands of Irish laborers worked on building the railroads in the United States. Some were able to save enough money to buy land and establish themselves as farmers along the routes they had helped to develop. This was especially true of Illinois and by 1860 there were 87,000 Irish people living in this state. Other Irish immigrants became coalminers in Pennsylvania. Working conditions in the mines were appalling with no safety requirements, no official inspections and no proper ventilation. When workers were victimized for trade union activity, they formed a secret society called the Molly Maguires. Named after an anti-landlord organization in Ireland, the group attempted to intimidate mine-owners and their supporters. The group was not broken-up until 1875 when James McParland, a Pinkerton detective and Irish immigrant, infiltrated the organization and his evidence resulted in the execution of twenty of its members. …