PowerPoint Slides - Duke Clinical Research Institute

advertisement

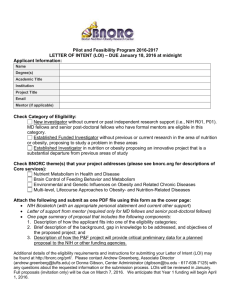

Writing Clinical Research Protocols, Part 2: Writing and Editing Clinical Research Protocols Jonathan McCall, BA Editor DCRI Communications Writing Clinical Research Protocols Writing Clinical Research Protocols ■ General Considerations ■ Parts of the Protocol ■ Good Writing Matters ■ Looking Ahead ■ Resources and Guidance Who Reads Protocols? ■ Keep the “audience” in mind: ■ Other physicians ■ Nurses/CRAs ■ Patients and their families ■ Patient advocates ■ IRB members ■ Scientific reviewers Using Templates ■ Many NIH programs encourage or require the use of protocol templates, such as the ones available here: ■ http://ctep.cancer.gov/guidelines/templates.html ■ Following template guidelines can help guide authors, but not every part of a template will necessarily apply in a given study. Writing Clinical Research Protocols ■ General Considerations ■ Parts of the Protocol ■ Good Writing Matters ■ Looking Ahead ■ Resources and Guidance Parts of the Protocol ■ Introduction ■ Safety/adverse events ■ Objectives (including study schema) ■ Regulatory guidance ■ Eligibility criteria ■ Study design/methods (including drug/device info) ■ Statistical section (including analysis and monitoring) ■ Human subjects protection/informed consent Adapted from: Protomechanics: Chapter 1 (http://www.cc.nih.gov/ccc/protomechanics/), CTEP Investigators’ Handbook, 2002 (http://ctep.cancer.gov/forms/Hndbk.pdf ) Background and Rationale ■ All protocols require a section detailing the scientific rationale for a protocol and the justification in medical and scientific literature for the hypothesis being proposed. ■ Introductory section should be as succinct as possible and should be organized in a logical, sequential flow. Background and Rationale ■ Double check all citations: ■ “Bibliographic inaccuracies harm the citing author and may cast doubt on the quality of the research being reported…” Wyles DF, Behavioral and Social Sciences Librarian, 2004 ■ “…[A]uthors should verify references against the original document.” Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals, ICMJE, 2005 (http://www.icmje.org/) Objectives ■ Objectives should be stated clearly as hypotheses to be tested. ■ Each objective should have a corresponding discussion in the statistical section. CTEP Investigators’ Handbook, 2002 (http://ctep.cancer.gov/handbook/index.html) Writing Eligibility Criteria STOP BEFORE YOU WRITE! ■ Eligibility criteria are the largest barrier to accrual to clinical trials.1 ■ Poorly written or poorly conceived criteria may undermine a trial’s generalizability and scientific validity.2 1Fuks A, J Clin Epidemiol, 1998 2George SL, J Clin Oncol, 1996 Writing Eligibility Criteria ■ Eligibility criteria—stated as either exclusion or inclusion criteria—define and limit the kinds of patients that can participate in a clinical trial. ■ Reasons for imposing eligibility criteria can include scientific rationales, safety concerns, regulatory issues, and practical considerations. George SL, J Clin Oncol, 1996 Writing Eligibility Criteria ■ Problems with restrictive criteria: ■ Limitations of generalizability ■ Failure to mimic clinical practice ■ Increased study complexity ■ Increased costs ■ Decreased patient accrual George SL, J Clin Oncol, 1996 Writing Eligibility Criteria ■ Recommendations: ■ The number of eligibility criteria should be kept to a minimum. ■ Criteria should include only those absolutely necessary to ensure scientific validity and patient safety. ■ Eligibility criteria should be clearly defined and verifiable by an external auditor. Adapted from: George SL, J Clin Oncol, 1996 Fuks A, J Clin Epidemiol, 1998 Writing Eligibility Criteria ■ Eligibility criteria should be straightforward and unambiguous. Which of these criteria would you choose? ■ Pregnant and/or nursing women are not eligible. ■ All women of childbearing age are required to have a serum pregnancy test. ■ Pregnant and/or nursing women are not eligible for this study. All women of childbearing potential (defined as…) must have a negative pregnancy test (serum or urine) within 2 weeks of study enrollment. Writing Eligibility Criteria ■ However, be aware of the consequences of highly specific criteria: ■ For example: consider the issues that will follow from mandating a particular serum concentration of some marker, rather than building the definition around institutional upper limits of normal. Study Design ■ The study design section of the protocol should contain a stepwise description of all procedures required by the study. ■ A good study design section includes sufficient information for the participating site to develop a comprehensive clinical pathway for study patients. Study Design ■ Parts of the study design section may include: ■ Initial evaluations ■ Screening tests ■ Required lab tests ■ Details of treatment and ancillary procedures ■ Agent information or device specifications ■ Dose scheduling and modification ■ Calendars Adapted from: Protomechanics: Chapter 1 (http://www.cc.nih.gov/ccc/protomechanics/) Safety ■ The Safety (or Adverse Events) section should include: ■ Detailed information for reporting adverse events, including reporting to the FDA and/or the sponsor ■ Unblinding processes (if applicable) ■ Lists of expected adverse events Human Subjects Protection ■ This section includes discussion of: ■ Subject selection and exclusion ■ Proposed methods of patient recruitment ■ Minority representation ■ Recruitment (or exclusion) of special subjects, including vulnerable subjects ■ Lists of potential risks and benefits, including justification for risks Adapted from: OHSR Information Sheet 5: Guidelines for Writing Research Protocols (ohsr.od.nih.gov/info/sheet5.html ) Model Informed Consent ■ The Office of Human Subjects Research recognizes 3 fundamental conditions for a valid informed consent: ■ Disclosure of relevant information to prospective research subjects ■ Comprehension of the information provided ■ Voluntary agreement of the subject, free from coercion Adapted from: OHSR Information Sheet 6: Guidelines for Writing Informed Consents (ohsr.od.nih.gov/info/sheet6.html ) Model Informed Consent ■ To these ends, the protocol model informed consent document must: ■ Be thorough and complete ■ Be written in simple, nontechnical language ■ Be carefully worded to avoid potentially coercive phrasing Model Informed Consent ■ OHSR recommends the following be included: ■ Statement that the study involves research ■ Purpose of the research and the length of the study ■ Description of risks and benefits ■ Discussion of alternative therapies ■ Confidentiality policy ■ Compensation for injury ■ Contact for further questions/information ■ Statement of voluntary participation Adapted from: OHSR Information Sheet 6: Guidelines for Writing Informed Consents (ohsr.od.nih.gov/info/sheet6.html ) Model Informed Consent ■ Writing a good MIC is a balancing act between being thorough, being accurate, and being as concise and simple as possible. ■ Patient advocates may offer invaluable experience and insight during the drafting and review phase of an MIC. Correlative Studies ■ Integrating correlative studies/basic science is a priority for the NIH: ■ “NIH Roadmap” initiative ■ Examples of correlative studies include: ■ Genomics ■ Proteomics ■ Pharmacokinetics ■ Decision-analysis studies Correlative Studies ■ A “protocol within a protocol,” with a similar structure listing rationale, methods, design, and analysis plans? Or, ■ Integrated into the main body of the protocol? The Statistical Section ■ Make sure that study objectives and study design elements in the statistical section mirror those in described in the Objectives section! ■ If the study involves stopping rules, make sure that descriptions and definitions of toxicities in the statistical section match those in the Safety/AE section. Writing Clinical Research Protocols ■ General Considerations ■ Parts of the Protocol ■ Good Writing Matters ■ Looking Ahead ■ Resources and Guidance Good Writing Matters “…Many existing clinical trials contain problems such as incompleteness, ambiguity, and inconsistency. Most of the errors are introduced during the protocol writing process…” Weng C, Medinfo, 2004 Good Writing Matters ■ Errors, omissions, or inaccurate or unclear material in technical writing can potentially result in: ■ Monetary loss ■ Damage to equipment ■ Loss of time ■ Loss of scientific value of research ■ Physical harm Blake G and Bly R, “Fundamentals of Effective Technical Writing,” The Elements of Technical Writing, 1993 Good Writing Matters ■ Costs of a badly written protocol? ■ Poorly written inclusion criteria have resulted in a number of ineligible and inevaluable patients being enrolled to a study. NOW WHAT? Good Writing Matters ■ To fix this problem, the protocol has to be amended. Remember: “Any change to the protocol document or Informed Consent that affects the scientific intent, study design, patient safety, or human subject protection is considered an amendment, and therefore must be approved by CTEP and your IRB…” NCI CTEP Amendment Request Submission Policy, Version Date May 14, 2004 (http://ctep.cancer.gov/guidelines/templates.html) Good Writing Matters ■ What are some potential costs in this scenario? ■ Patient distress ■ Study design compromised ■ Accrual delay (possibly measured in months) ■ Administrative costs of submitting and approving amendment (coordinating center and sites) ■ Site goodwill Tools for Better Writing ■ Appoint a dedicated editor to oversee the drafting and compilation of a protocol. ■ Adopt standard references for your protocol. ■ Many eyes make accurate work: review both among and outside of the team can make the difference. Tools for Better Writing: Style Sheets ■ Establishing a list of common style elements can help maintain uniformity and consistency in protocols: ■ Preferred punctuation ■ Preferred citation style ■ Layout and organization of protocols ■ Templates for calendars and schedules ■ Common data elements Tools for Better Writing: Proofreading ■ Make time for proofreading ■ Don’t make last-minute changes and submit a document for review or approval without subjecting it to a formal proofreading. ■ Once is not enough ■ Remember: protocols are lengthy, complex documents. You will need more than single review to catch all mistakes. Tools for Better Writing: Proofreading ■ Fresh eyes ■ Working too long on a protocol may habituate eyes and brains to mistakes, simply because they’ve been there all along. Get an “outside” reviewer! ■ Spell-checkers, etc. ■ A document that has been “checked” by automatic software has NOT been proofread. Avoiding Pitfalls: Inconsistency ■ Adopt and apply standards for: ■ Procedure names ■ Agents and devices (Remember: avoid trade names!) ■ Abbreviations ■ Units Avoiding Pitfalls: Ambiguity ■ Use precise language. ■ Are spans of time inclusive or exclusive? ■ Identify procedures as specifically as possible (eg, “balloon angioplasty” rather than “heart surgery”). Writing Clinical Research Protocols ■ General Considerations ■ Parts of the Protocol ■ Good Writing Matters ■ Looking Ahead ■ Resources and Guidance Looking Ahead ■ Even the best protocols may have to be amended, due to: ■ Changes in the scientific or clinical landscape ■ Regulatory changes, including updated procedures ■ Unforeseen clinical developments that may affect patient safety or study validity Looking Ahead ■ Avoid being “reactive” when amending protocols ■ Seize the opportunity to review the entire protocol; this “continuing review” may uncover errors or omissions that passed through earlier reviews. ■ Don’t just make a “point” change to a protocol; check the entire document for ramifications. Looking Ahead ■ Remember: maintain version control! ■ Archive EVERYTHING! ■ Control access to materials: ■ Have a defined procedure for creating or modifying files ■ Limit write-access to files, where appropriate Writing Clinical Research Protocols ■ General Considerations ■ Parts of the Protocol ■ Good Writing Matters ■ Looking Ahead ■ Resources and Guidance NIH Guidance on Protocol Writing ■ Protomechanics: http://www.cc.nih.gov/ccc/protomechanics/ ■ The Office of Human Subjects Research: http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/info/info.html ■ The NCI Investigators’ Handbook: http://ctep.cancer.gov/handbook/index.html Templates ■ The NIH phase III template: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/funding/research/ clinical_research/ProtocolTemplate.htm ■ The Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) Templates (phases I–III; based on NIH model): http://ctep.cancer.gov/guidelines/templates.html Informed Consents ■ Office of Human Subjects Research http://ohsr.od.nih.gov/info/info.html ■ The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP): http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/index.html#informed Writing Resources ■ The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME) Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals http://www.icmje.org/ Writing Resources ■ The American Medical Association style manual may provide a useful “default” reference for protocol writing: Cheryl Iverson, Chair. The American Medical Association Manual of Style. 9th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1998. ■ The Duke University Medical Center Library maintains a select bibliography of style guides at: http://www.mclibrary.duke.edu/subject/style Summary ■ Writing a clinical protocol is an elaborate, collaborative task that will require the talents of many contributors to ensure a result that is scientifically sound and logistically practicable. ■ The quality of writing in a protocol and the quality of the protocol itself are inseparable. Questions?