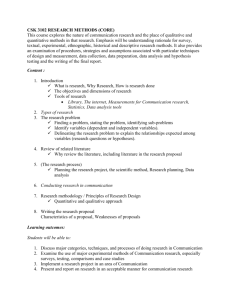

Real Estate Interests as Securities - Florida State University College

advertisement

Real Estate Interests as Securities • Question arises under – federal law and – state law. • Federal law: classically, mandates full disclosure. The issuer of securities files a registration statement that includes a prospectus designed to summarize the offering for the public, particularly its risks. – The traditional federal policy is merely one of disclosure. • So long as you disclose the risk, even if it is very high risk, you may then offer the securities for sale. • State law: varies, but at the classic historic extreme, required an offering to be “fair, just and equitable” before it could take place within the state. • Today, much of state law has been preempted by federal law. 1 Donald J. Weidner Real Estate Interests As Securities • Federal and state statutory definitions of “security” tend to parallel one or another – even though the underlying policies of state and federal law have in the past diverged significantly. • Federal and state case law developments on what constitutes a “security” inform one another – but there are differences. • Joiner Leasing and Howey are two major real estate cases from the 1940s that indicate that interests in leaseholds and in fees simple can be securities within the meaning of the federal securities laws. 2 Donald J. Weidner SEC v. C.M.Joiner Leasing Corp. 320 U.S. 344 (1943) • Promoter acquired a lease on 4,700 acres of potentially oil-bearing land. • Promoter sold investors partial assignments of its leasehold interest – in parcels ranging from 2.5 to 20 acres. • In addition, the Promoter also promised each investor that he would explore for oil. • When the SEC attempted to restrain the Promoter, he asserted that he was only selling “mere” interests in real estate, not securities. – Securities are financial products like stocks and bonds, he said, not direct interests in real property. 3 Donald J. Weidner Joiner Leasing (cont’d) • Supreme Court held for the SEC: Promoter was selling more than “naked leasehold rights,” he was also trading in the economic inducements of the proposed exploration well. – The package arrangement, of the leasehold interest coupled with the contract to explore, falls within the concept of “investment contract.” • Often-quoted language: “The reach of the Securities Act does not stop with the obvious and commonplace. Novel, uncommon or irregular devices are also reached if . . . they were widely offered or dealt in under terms or courses of dealings which established their character in commerce as ‘investment contracts,’ or ‘as any interest or instrument commonly known as a ‘security.’” 4 Donald J. Weidner SEC v. W.J.Howey Co. 328 U.S. 293 (1946). • Promoter publicly offered for sale strips of Florida citrus acreage; – buyers received fees simple absolute by warranty deeds. • To avoid the Joiner Leasing problem, the Promoter avoided mandatory service contracts. • However, for an extra cost, investors could enter optional service contracts under which – the Promoter agreed to cultivate the acreage and pay the net profits to the purchaser of the land. • Most, but not all, of the purchasers of land also purchased service contracts. • As in Joiner Leasing, the Promoter argued that he sold mere interests in real estate, not “securities.” 5 Donald J. Weidner Howey (cont’d) • Supreme Court was unmoved by the fact the service contracts were optional. – It said that individual development was unlikely • Stating what is probably the most cited language in all Securities law: An investment contract is a “scheme whereby a person [1] invests his money [2] in a common enterprise and [3] is led to expect profits [4] solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party.” – A rule courts have been parsing for decades. • Both Joiner Leasing and Howey seem to say: The form of the investment unit, whether a stock certificate or a warranty deed, is immaterial. The question is whether, in substance, the unit is a security. – As in mortgage law, the question is substance over form 6 Donald J. Weidner Solely Through the Efforts of Others • HYPO: An investor contributes $x to become a limited partner in a liquor store. The investor is required to work in the store for several days during each yearend holiday season. • Does the limited partnership form of the investment foreclose classification as a security? – Not according to Howey • Does the fact that the limited partner’s profits are not solely through the efforts of others foreclose classification as a security? – Given the use of the word “solely” in Howey? • Even state courts were quick to distance themselves from the “solely” requirement – If not “solely,” then what? • Glenn Turner is a leading case 7 Donald J. Weidner SEC v. Glenn W. Turner Enterprises, Inc. (on the “efforts of others” prong of Howey) 474 F.2d 476 (9th Cir. 1973) • Involved the sale of “self improvement” contracts by Dare To Be Great, Inc., – a Florida Corporation that was a wholly-owned subsidiary of Glenn W. Turner Enterprises, Inc. • In short, purchasers acquired the right to take a selfimprovement course [ranging in price from $300 to $5,000]. • The purchaser was required to exert great effort, attend meetings and self-improve. • Meetings were like revivals, much chanting, jubilation, even “money humming.” 8 Donald J. Weidner Glenn W. Turner Enterprises (cont’d) • “Although mention of ‘money-humming’ is made at several points in the record, we are not certain what this activity entails, nor do we venture to guess.” 474 F.2d at 479, n. 2. • Purchaser can profit by selling courses to others. • As to the “solely” test: “We adopt a more realistic test, whether the efforts made by those other than the investor are the undeniably significant ones, those essential managerial efforts which affect the failure or success of the enterprise.” 9 Donald J. Weidner Silver Hills Country Club v. Sobieski (on “profits” prong of Howey) 361 P.2d 906 (Cal. 1961). • Promoter sold 110 “Charter Memberships” in a country club for $150 each. The club was under construction and expansion. • Subsequent memberships were to be sold, and at higher prices. • The prices were expected to rise as additional facilities (ex., a golf course) were constructed. • Members had to pay monthly country club dues. • Members could be expelled only for misbehavior or for failure to pay dues. • Membership was transferable, but only to persons approved by the club’s Board of Directors. • Members had no rights to the income or assets of the club. 10 Donald J. Weidner Silver Hills (cont’d) • Because the promoters were to receive all the profit left over from the construction and operation of the club facilities, the purchasers were not getting and profit in the usual sense. • Other jurisdictions had said “no security” because there was no expectation of profit by the purchasers. • However, the California court focused on the promoter raising risk capital: “We have here nothing like the ordinary sale of a right to use existing facilities. Petitioners are soliciting the risk capital with which to develop a business for profit.” – “Since the act does not make profit to the supplier of capital [the offeree] the test of what is a security, it seems all the more clear that its objective is to afford those who risk their capital at least a fair chance of realizing their objectives in legitimate ventures whether or not they expect a return on their capital in one form or another.” 11 Donald J. Weidner Brown v. Rairigh (on “common enterprise” prong of Howey) PR man has 15 (Supp. P. 101) Pays $11,675 Cash on 2/74 10% interest in 5 horses 10% of all winnings Agrees to shoulder 10% of all expenses Option to purchase a further 25% interest in same 5 horses based on value at 2/74 PR horses (but is not in business of promoting and selling percentage interests in race horses. Only once before had he sold an interest in any of his horses). That is, equivalent to a share, not of gross receipts, but of profits. Gets right to PUT the 10% interest back to the PR man; the PUT is exercisable by 1/1/75 at a price = FMV at time of the exercise of the PUT. PR man retains custody and control of the 5 horses. 12 Donald J. Weidner Brown v. Rairigh (cont’d) ‘s put expired. claimed he was sold an unregistered security and demands rescission under Florida’s “Blue Sky” law. Recall the now slightly modified basic definition of an investment contract from Howey: 1) an investment of money 2) in a common enterprise 3) with an expectation of profits 4) solely (or primarily) through the essential managerial efforts of a promoter or a third party. Investment of money is clear here. Was there a “common enterprise?” 13 Donald J. Weidner Brown v. Rairigh (cont’d) Brown v. Rairigh notes 3 different approaches to the “common enterprise” requirement: 1. A one-on-one dealing between offeror and offeree is sufficient. 2. It is sufficient if the transaction’s success depends on multiple investors, even if there is no interaction among those investors. 3. There must be both a. more than one investor and b. interaction between or among those investors. 14 Donald J. Weidner Huberman v. Denny’s Restaurants, Inc. (on common enterprise/efforts of others) 337 F.Supp. 1249 (N.D. Cal. 1972). Operator Dev. agrees to build Dev. Operator Conveys 20 year lease Dev. Operator Agrees to pay rent: Dev. Fixed minimum + 5% of monthly gross sales Dev. sells fee Buyer Assume Buyer discovers she has made a bad deal, but there is no fraud or misrepresentation. May Buyer claim that she purchased a security? There was an investment of money. Was there a common enterprise? With profits to come solely through the efforts of others? 15 Donald J. Weidner Huberman v. Denny’s Restaurant (cont’d) • As to “common enterprise”: – “Plaintiff as owner of the building and land not only had the landlord’s natural interest in the well being of her tenant but the significant interest in the amount of additional ‘rent’ from the lease that was dependent on the volume of the restaurant sales. Therefore, since plaintiff [buyer] and defendants [operator] had a common interest in the success of the venture, a ‘common enterprise’ has been properly alleged for purposes of coming within the Howey test.” 16 Donald J. Weidner Huberman v. Denny’s Restaurant (cont’d) • As to “solely through the efforts of others”: – “She was not buying a franchise restaurant to manage and defendants have not claimed that plaintiff ever showed any intention of running the franchise herself. She was looking solely to the efforts of Denny’s and the other defendants for the profits: First, in the guaranteed rental that they had put in their lease, and second by the successful running of the franchise which would increase her ‘rental’ receipts with the increase in sales.” 17 Donald J. Weidner Brown v. Rairigh: First rationale for denying recovery (no “common enterprise”) • Brown rejected Huberman: “it goes too far because it reduces the word ‘common’ to mere surplusage and the word ‘enterprise’ is all that is left.” • Should it make a difference if the racehorse purchaser had purchased jointly with a friend or spouse? • In this case, is the victim the buyer or the seller? – “There is no concomitant protection for unsophisticated sellers who are persuaded to sell part of their business by purchasers, the latter knowing full well that they have an absolute out, plus interest and attorneys fees, if the business flounders.” 18 Donald J. Weidner Brown v. Rairigh: Second rationale for denying recovery (estoppel) Obviously uncomfortable with its “common enterprise” rationale, the court offered an alternative rationale for deciding against the plaintiff investor: “If an investor is fully informed as to all aspects of his investment prior to purchase and if he is fully aware of the use to which his proceeds will be put, then in such event his conduct, when considered together with other facts and circumstances, may well estop him from seeking relief under the Blue Sky Laws, providing however that the promoter or issuer is not in the business of promoting or issuing . . . .” 19 Donald J. Weidner Brown v. Rairigh: A Third Possible Rationale • Did the plaintiff and the defendant become partners? • The third rationale is that the situation is more properly governed by partnership law rather than by securities law. • We shall see subsequent cases in which the courts, in deciding whether to expand the concept of “investment contract,” ask whether there is some other law, other than securities law, that provides sufficient protection to the person claiming to have purchased a security. • In Brown v. Rairigh, it seems clear that the plaintiff and the defendant formed an inadvertent partnership. They were co-owners of a business for profit who also shared losses. 20 Donald J. Weidner Williamson v. Tucker (5th Cir.) (on unusual cases in which an interest in a partnership is a security) • A general partnership or joint venture interest can be a security in special circumstances: (1) if the agreement among the parties leaves so little power in the hands of a partner or venturer that power is distributed as in a limited partnership [emphasis on the agreement]; (2) if a partner or venturer is so inexperienced and unknowledgeable as to be incapable of intelligently exercising the partner or venturer’s powers [emphasis on the investor]; or 21 Donald J. Weidner Williamson v. Tucker (cont’d) (3) if a partner or venturer is so dependent on some unique entrepreneurial or managerial ability of the promoter or manager that the partner cannot – replace the manager or – otherwise exercise meaningful partner or joint venturer powers. [Emphasis on the manager]. • We’ll see further case law on this issue. 22 Donald J. Weidner United Housing Foundation, Inc. v. Forman (Supplement p. 105) • Mitchell-Lama Act project for low-cost cooperative housing. N.Y. Housing Finance Agency provided 40year, Below Market Interest Rate loans to the developer, who also received substantial tax exemptions. • Developer agreed to operate on a nonprofit basis and lease only to people with incomes below a certain level who had been approved by the state. • The motivating force was United Housing Foundation (UHF), a nonprofit corporation composed of labor unions, housing cooperatives and civic groups. – UHF had sponsored the construction of several major N.Y. co-ops. 23 Donald J. Weidner United Housing Foundation, Inc. v. Forman (cont’d) • Those who wished to occupy the apartments were required to purchase shares of stock in the Riverbay Corporation – Which was organized by UHF • Riverbay Corporation was organized to own and operate the buildings that constituted the project known as “Co-op City” • The number of shares in Riverbay a purchaser was required to buy depended upon the size of the apartment the purchaser wanted to occupy. – Ex., the cost of the 72 shares needed for a 4-BR apartment was $1,800. – “[I]n effect, [the share] purchase “is a recoverable deposit on an apartment.” 24 Donald J. Weidner Forman (cont’d) • Shares were explicitly tied to the apartment, – they could not be transferred to a non-tenant, – they could not be pledged or encumbered. – they descended, along with the apartment, only to a surviving spouse. • Each shareholder-occupant was entitled to one vote—the vote attached to the apartment, not to the shares. • Any occupant who wanted to vacate was required to offer the stock back to the corporation at cost. 25 Donald J. Weidner Forman (cont’d) • In 1965, Riverbay circulated offering literature that estimated an anticipated construction cost of $280 million. – With an average cost of $230 per room • The final HFA blanket mortgage, the debt service on which was to be paid out of the “rent” from the shareholder-tenants, was 50% more than originally estimated, at more than $400 million. – With an average cost of $400 per room (almost double that announced in the offering literature). 26 Donald J. Weidner Forman (cont’d) • It is clear that, if this were a security, there was a violation of the securities law because of the failure to disclose the following material facts: – the estimated cost of construction was very low; and – this sponsor had a prior history of cost-overruns; – CSI, the general contractor and sales agent, was a wholly-owned subsidiary of UHF; – CSI had insufficient liquidity to complete the project and – the State Housing Commission had waived the liquidity requirements to approve CSI as the contractor. 27 Donald J. Weidner Forman (cont’d) Most basically, the purchasers sued under §10b of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934: “It shall be unlawful for any person in the offer or sale of any securities by the use of any means or instruments of transportation or communication in interstate commerce or by use of the mails, directly or indirectly(1) to employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud, or (2) to obtain money or property by means of any untrue statement of a material fact or any omission to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading [that is, non-disclosure is a violation], or (3) to engage in any transaction, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon the purchaser.” 28 Donald J. Weidner Forman (at 2d Circuit) • The Question: was there a sale of a “security.” – The purchasers say their “stock” was “stock” within the statutory definition of “security.” • The 2d Circuit held there was a “security,” finding three sources of expected “profit” for the purchasers: (1) rent reductions through income generated from the leasing of commercial facilities, professional offices and parking spaces and from community washing machines. (2) tax deductions for the portion of each occupant’s “rent” that was traceable to interest on the mortgage encumbering the project. (3) rent reductions through subsidies. 29 Donald J. Weidner Forman (at Supreme Court) • The Supreme Court reversed, stating that, even though the interests the occupants purchased were called “stock”: – “they lack . . . the most common feature of stock: the right to receive ‘dividends contingent upon an apportionment of profits’.” • The Court said the interests also lacked “the other characteristics traditionally associated with stock”: – they are not negotiable; – they cannot be pledged or hypothecated; – they confer no voting rights in proportion to the number of shares owned; and – they cannot appreciate in value. 30 Donald J. Weidner Forman (Supreme Court, Cont’d) • “In short, the inducement to purchase was solely to acquire subsidized low-cost living space, it was not to invest for profit.” • Supreme Court said there was no expectation of profit – “By profits, the Court has meant either [a] capital appreciation resulting from the development of the original investment . . . or [b] a participation in earnings resulting from the use of investor funds . . . .” • Supreme Court adopted Glenn Turner “entrepreneurial or managerial” spin on the “solely or primarily” test. – “The touchstone is the presence of an investment in a common venture premised on a reasonable expectation of profits to be derived from the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others.” 31 Donald J. Weidner Forman (Supreme Court rejected 2d Circuit’s finding of “profits”) A. Tax Benefits 1. There is no authority that a payment of rent used to pay interest is a profit because it has become deductible. 2. The deductibility of interest as an owner in Co-Op City is no greater than that of any other homeowner. 3. Deductibility does not result from the managerial efforts of others. B. Subsidies. 1. Can not be liquidated for cash. 2. Do not result from the managerial efforts of others. 32 Donald J. Weidner Forman (Supreme Court Rejected the 2d Circuit’s finding of profits) C. Net Income from Commercial Rental, Parking, Washing Machines. 1. Is far too speculative and insubstantial. 2. May be properly viewed as a rebate 1. from facilities patronized only by the tenants. 3. Was never an inducement because it was never mentioned in the offering circular. 4. Facility leases were made to provide essential services to tenants, rather than to generate profit by providing services to others. 33 Donald J. Weidner Forman (rejects Silver Hills and finds only limited risk) • Supreme Court declined to adopt California’s Silver Hills (risk capital) approach. • Alternatively, even under risk capital, this investment does not meet the test because the purchasers “take no risk in any significant sense.” – “[I]n view of the fact that the State has financed over 92% of the cost of construction and carefully regulates the development and operation of the project, bankruptcy in the normal sense is an unrealistic possibility.” – “[T]he risk of insolvency of an ongoing housing cooperative ‘differ[s] vastly’ from the kind of risk of ‘fluctuating’ value associated with securities investments.” 34 Donald J. Weidner Analog to 10b • Fla. Stat. 517.301(1) is a provision that echoes the ‘34 Act’s 10b • Florida’s nondisclosure rule, however, is more broad. It applies – “In connection with the rendering of any investment advice” and – “in connection with the offer, sale, or purchase of any investment or security” 35 Donald J. Weidner Wals v. Fox Hills Dev. Corp.(7th Cir. 1994) (Supplement p. 135) • 1990, Buyers purchased “‘week 5” of an apartment, which is in February, in a recreational condominium project outside Manitowoc, Wisconsin, that featured an extraordinary golf course. • Contemporaneously, Buyers entered into two agreements that were renewable annually: 1. A “flexible time” agreement, under which Buyers could swap their week in February for a week in the summer; and 2. A supplement to the “flexible time” agreement called the “4share program,” under which: a. the Buyers agreed not to occupy the unit during the summer week obtained by the swap; b. the Developer was authorized to rent the unit during the summer week; with c. the Buyers receiving the summer rental minus a 30% fee to the Developer. 36 Donald J. Weidner Wals v. Fox Hills Dev. Corp. (cont’d) • Buyers claimed: – that the side agreements constituted an “investment contract” within the definition of “security” – that the securities were not registered with the SEC – that therefore they were entitled to rescind the sale of an unregistered security. • Judge Posner said that the effect of the supplemental agreements was “to reduce the cost to them of their investment in their own unit.” – Reminiscent of Forman’s “rebate” language • “Nothing is more common than for the developer . . . to offer to rent out owned but temporarily unoccupied units as the agent of the owner.” 37 Donald J. Weidner Wals v. Fox Hills Dev. Corp. (cont’d) • Judge Posner recognized that some other circuits would hold this a security: “Because the resulting division of rental income makes the developer and the condominium owner coventurers in a profit-making activity, imparting to the condominium interest itself the character of an investment for profit . . . , those circuits that believe that only ‘vertical commonality’ is required to create an investment contract would deem the combination of sale and rental agreement in this case an investment contract.” 38 Donald J. Weidner Wals v. Fox Hills Dev. Corp. (cont’d) • “Other circuits, including our own, require more—require ‘horizontal commonality,’ that is, a pooling of interests not only between the developer or promoter and each individual ‘investor’ but also among the ‘investors’ (the owners of the condominiums, in this case)—require, in short, a wheel and not just a hub and a spoke.” 39 Donald J. Weidner Wals v. Fox Hills Dev. Corp. (cont’d) • “The benefits [of a real estate “investment”] can be pecuniary or nonpecuniary, but the combination of the ‘flexible time’ agreement with the ‘4-share’ program converts the condominium owner’s investment, even if only temporarily, into a purely pecuniary investment, for the owner obtains no consumption value from his property when he is not occupying it.” • “Even so, the optional character of the ‘flexible time’ and ‘4-share’ agreements makes it difficult to conceive of the sale of the condominium itself as the sale of a security.” – However, the contracts were optional in Howey 40 Donald J. Weidner Wals v. Fox Hills Dev. Corp. (cont’d) • Here, the unit owner “receives the particular rental on that unit rather than an undivided share of the total rentals of all the units that are rented out. The nature of his interest thus is different from that of a shareholder in a corporation that owns rental property.” • The Buyers “did not receive an undivided share of some pool of rentals or profits. They received the rental on a single apartment, albeit one not owned by them (for it was not their week).” • “There was a pooling of weeks, in a sense, because the [Buyers] selected their summer swap week from a ‘pool’ of available weeks. But there was not a pooling of profits, which is essential to horizontal commonality.” 41 Donald J. Weidner Wals v. Fox Hills Dev. Corp. (end) • The requirement of uniform disclosure to investors “only makes sense if the investors are obtaining the same thing, namely an undivided share in the same pool of assets and profits.” – Or if the purchased interests are fungible? • “We can imagine a case . . . in which undeveloped lots are marketed on a large scale to unsophisticated investors who neither inspect their lot before buying it nor ever build or occupy a home on it—it is for them a purely speculative investment—and while there is no pooling of profits the investors regard the lots as fungible.” 42 Donald J. Weidner Condominia As Securities—Relevant Structural and Circumstantial Factors: Most Suggestive Factors at Top • • • • • • Structural Time Sharing Mandatory Rental Pool Rental Agent Predetermined Developer Retains Management Control Optional Rental Pool Other Income Generation • • • • 43 Circumstantial Emphasis on Profits Through Rents Emphasis on Appreciation of Particular Developer’s Projects Individuals purchase several units Part-time occupancy the rule Donald J. Weidner Structural and Circumstantial Factors (cont’d) • • • • • • Structural Long Notice to Occupy – Especially during prime season Freedom to choose rental agent No rental agent Existing subdivision lot plus house to be built Lot Completed house on lot Circumstantial • Purchasers live far from unit • Year-round occupancy the rule • Sales pitch based on place to live 44 Donald J. Weidner Registration Pressure Lifted • Stuart Saft, Structuring Condominium Hotels, New York Law Journal (March 11, 2013): – “[A] small change in the federal securities laws contained in the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (the JOBS Act) [2012] could be used to permit the nationwide sale of condominium units with . . . rental pools without the need . . . to register the offerings with the SEC. The JOBS Act permits sponsors to acknowledge that the units are securities, but by expanding an exemption under Regulation D, obviates the need to register with the SEC if all of the investors are accredited investors.” • 10b-5 still applies. • Blue Sky laws must also be checked. 45 Donald J. Weidner Marine Bank v. Weaver (1982) (Supplement p. 138) 2/28/78 Weavers (Sam & Alice) $ $50,000 CD Marine Bank 6 year CD FDIC insured up to $40,000 LESS THAN 3 WEEKS LATER 3/17/78 Weavers Pledged the CD to guarantee Bank loan of $65,000 to Columbus Packing Co. “In consideration for guaranteeing the loan”, Columbus’ owners agreed to give the Weavers: Columbus Packing Co. 1) 50% of Columbus’ net profits for the life of the guarantee; 2) $100 per month for the life of the guarantee; A. Already owed Marine Bank $33,000 for prior loans; and 3) right to use the Columbus barn and pasture at the discretion of the owners of Columbus Packing Co; and B. Was substantially overdrawn on its checking account. 4) right to veto future borrowing of Columbus Packing Co. 46 Marine Bank In short, all but $3,800 of the $65,000 was used to satisfy prior bank claims (the bank kept $42,800 to itself) and the claims of other creditors. The Weavers say the bank solicited their guarantee and told them the $65,000 would be used as working capital. Columbus is belly up. Bank is poised to go for the Weavers’ CD. The Weavers cry “security.” Donald J. Weidner Marine Bank (cont’d) • Justice Burger seemed to reject the most expansive reading of Howey. • Court’s starting point: The Act was adopted to restore investor confidence in the financial markets. • Court cites Howey but does not quote it or state its test. • Justice Burger’s “test” is “what character the instrument is given in commerce” by – the terms of the offer, – the plan of distribution, and – the economic inducements held out to the prospect. • He then admonishes against expanding the definition of security too far: “Congress, in enacting the securities laws, did not intend to provide a broad federal remedy for all fraud.” 47 Donald J. Weidner Marine Bank: the CD itself • Purchasers received a fixed rate of interest rather than dividends based on the bank’s profits. • Purchasers received no voting rights. • The CD differs from other long-term debt obligations because it “was issued by a federally regulated bank which is subject to the comprehensive set of regulations governing the banking industry.” – Therefor less risky? • There is a long history that nearly all depositors in failing banks receive full payment, even beyond the insured amount. 48 Donald J. Weidner Marine Bank: the CD itself (cont’d) • “It is unnecessary to subject issuers of bank certificates of deposit to liability under the antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws since the holders of bank certificates of deposit are abundantly protected under the federal banking laws.” – Note the interesting and fundamental jurisprudential point—it is “unnecessary” to interpret a statute a particular way because other law provides sufficient protection. 49 Donald J. Weidner Marine Bank: the loan guarantee • 3d Circuit had emphasized: Purchasers received a share of the slaughterhouse profits that would result from the efforts of its managers. • Reversing, the Supreme Court stated: Congressional intent was to cover [only] “those instruments ordinarily and commonly considered to be securities in the commercial world.” • “The unusual instruments found to constitute securities in prior cases involved offers to a number of potential investors, not a private transaction as in this case.” 50 Donald J. Weidner Marine Bank: the loan guarantee (cont’d) • Here, by contrast: – the Company distributed no prospectus to the purchasers or to anyone else. – the unique agreement they negotiated was not designed to be traded publicly (underscored by the use of barn and pasture). – the provision that gave the purchasers the right to veto future borrowing gave them a measure of control “not characteristic of a security.” 51 Donald J. Weidner Marine Bank (conclusion) • On the one hand: – “[W]e hold that this unique agreement negotiated one-on-one by the parties, is not a security.” • On the other hand: – “It does not follow that a . . . business agreement between transacting parties invariably falls outside the definition of a security as defined by the federal statutes.” • Effect on Denney’s Restaurants? • Effect on Brown v. Rairigh? 52 Donald J. Weidner Rivanna Trawlers Unlimited v. Thompson Trawlers, Inc. (1988) (Supplement p. 148) • August, 1982, Rivanna Trawlers (“RTU”) was formed when 23 parties executed a general partnership agreement to “acquire, own, lease and operate multipurpose [commercial] fishing vessels” – Why was a general partnership used? • August 30, 1982, RTU purchased 4 fishing boats and entered an agreement for their management and maintenance with Thompson Management, Inc. • Spring, 1983, the partners were concerned with operations and considering management changes. • The partners – replaced RTU’s external managers twice and – removed RTU’s original managing partner and replaced him with a committee. 53 Donald J. Weidner Rivanna Trawlers (cont’d) • A number of the partners claim they purchased securities without the full disclosure required by Section 10b-5 • They sued, among others, the original managing partner and the original external manager. • 4th Circuit, through former U.S.S.Ct. Justice Powell, says the “critical issue” is the “solely from the efforts of others” prong of Howey: “General partnerships ordinarily are not considered investment contracts because they grant partners—the investors—control over significant decisions of the enterprise.” – Marine Bank said the power to veto future loans was more control than usually found in securities. – General partners typically have much more power than a right to veto future loans. 54 Donald J. Weidner Rivanna Trawlers (cont’d) • How much investor control negates a finding that profits are “solely through the efforts of others?” • Williamson is a “narrow exception” to the “strong presumption” that a general partnership interest is not a security. • A partnership “can be an investment contract only when the partners are so dependent on a particular manager that they cannot replace him or otherwise exercise ultimate control.” • FN 5: It is not necessary that they be able to replace a manager with themselves, it is enough that they are reasonably capable of finding a replacement manager. • Further, partners can not turn their investment into a security by remaining passive. 55 Donald J. Weidner Rivanna Trawlers (cont’d) • The “critical inquiry” is into the powers given the general partners under the partnership agreement. • Issue is whether “those powers are sufficient to allow the general partners to exercise ultimate control, as a majority, over the partnership and its business.” • If the agreement gives a majority of the general partners the power to control the business, the presumption of no security “can only be rebutted by showing that it is not possible for the partners to exercise those powers.” 56 Donald J. Weidner Rivanna Trawlers (cont’d) • Even if general partners do not individually have decisive control over major decisions, “they do have the sort of influence which generally provides them with access to important information and protection against a dependence on others.” • Congress “did not intend to provide a federal remedy for all common law fraud.” (citing Marine Bank) 57 Donald J. Weidner Rivanna Trawlers (cont’d) • A court should not “look to the actual knowledge and business expertise of each partner in order to assess his or her individual ability intelligently to exercise the power of a general partner.” – “Such an inquiry would undercut the strong presumption that an interest in a general partnership is not a security.” – “It would also unduly broaden the scope of the Supreme Court’s instruction that courts must examine the economic reality of partnership interests.” • Don’t look too closely – The complaints and briefs “properly speak only in terms of the partners as a group.” 58 Donald J. Weidner Rivanna Trawlers (The Agreement) • Policy and management decisions required a vote of 60% in interest – including a vote to dissolve. • At all times, each partner had – reasonable access to the partnership’s books (mandatory under partnership law) and – the right to demand an audit. • The partnership agreement required unanimous consent to: – transfer partnership interests – admit additional partners – distribute profits other than in proportion to their respective interests. 59 Donald J. Weidner Rivanna Trawlers (cont’d) • What the court says about Virginia law in FN 8 is the law in every state. • Each state has default rules that provide for – equal management rights, – delectus personarum (choice of the person), – unanimous consent required to contravene the partnership agreement and – inspection and copying rights, • except that many states no longer require the right to inspect and copy “at all times.” • “Normally, [the authority to manage their investments] renders unnecessary the protection of the federal securities laws.” – Recall the word “unnecessary” in Marine Bank 60 Donald J. Weidner Rivanna Trawlers (cont’d) • “An investor who has the ability to control the profitability of his investment either by his own efforts or by majority vote in group ventures, is not dependent upon the managerial skills of others.” • These partners both had the authority and exercised it. • “The fact that some of the general partners . . . lacked financial sophistication does not affect the result. * * * [M]embers of a general partnership who lack financial sophistication or business expertise nevertheless may exercise intelligently the powers conferred on them by the partnership agreement and state law.” – They have access to information and can consult lawyers and accountants. • “The real gravamen of appellant’s complaint lies in common law fraud.” 61 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (9th Cir. 1991) (Supp. P. 154) • 160 doctors, dentists and their relatives each invested between $23,000 and $500,000 in general partnerships formed to purchase land to grow jojoba. – Why were high net-worth individuals put in general partnerships? • Several of the promoters were accountants of the investors. • The lawyer-promoter, who drafted the documents, had represented several of the investors. • 35 general partnerships (averaging 4.5 partners each) were formed and each partnership purchased 80 acres from “selling corporations” owned by the promoters – who had purchased the land from a common grantor. 62 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (cont’d) • Investors allege they were told it was not economically feasible to farm jojoba in 80acre tracts – they saw themselves as buying shares in a 2,700 acre plantation. • There was a common manager and field office for all the general partnerships. • Promoter was to sell Jojoba seeds and other supplies to the partnerships. • Each partnership agreement specified one operating general partner and a number of other general partners. 63 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (cont’d) • Court: “within each partnership,” the general partners have full control of the business: – they can make decisions by majority vote. – they can remove managers by majority vote. – they can access partnership books and records. • None of the investors knew anything about jojoba farming. • Indeed, few in the United States knew anything about jojoba farming. 64 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (cont’d) • There was dispute about the actual participation of investors – Promoters said some of the investors were very active. – Investors said they were passive. • Investors allege: even the investors who nominally were operating general partners merely acted as conduits for materials created by the promoters – including assessments to each partner for expenses. • On appeal from summary judgment, the plaintiffs’ allegations were accepted as true. 65 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (and Williamson) • Court’s starting point was Howey’s “control” test. • Court then looked to Williamson (5th Cir.) to apply the control test to general partnerships. • Williamson looks ex ante and not ex post – In contrast with Rivanna Trawlers • Williamson looks both at the legal ability to control and at the practical ability to control. 66 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (and Williamson) 1. The first Williamson factor focuses on the agreement – The issue: does the agreement allocate powers as they would be allocated in a limited partnership? – The first Williamson factor “is addressed to the legal powers afforded the investor by the formal documents without regard to the practical impossibility of the investors invoking them.” 67 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (first Williamson factor) • “As a legal matter, the partners have the authority and responsibility to control every aspect of the jojoba cultivation process.” – additional assessments of capital must be approved by 75% of the partnership. – a majority of the units can remove any person from a management position. – decisions about management must be made by a majority vote. • Therefore, the promoters who sought to avoid a finding of control “primarily through the efforts of the promoter or of a third party” passed muster under the first Williamson factor. 68 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (second Williamson factor) 2. The second Williamson factor focuses on the investor – The issue: is the investor too inexperienced and unknowledgeable to intelligently exercise the powers the investor has under either the partnership agreement or under partnership law? • Lack of knowledge about jojoba farming is not dispositive. • They each had $23,000 or more to invest (and is therefore sophisticated?). • Because there was an insufficient record on this issue, the court remanded. • What did Rivanna Trawlers say? 69 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (third Williamson factor) 3. The third Williamson factor focuses on the promoter or manager • The issue: is there a unique entrepreneurial or managerial ability in the promoter or manager such that the partner (presumably, the partners as a group) cannot replace the manager or exercise meaningful partnership powers? • Here, there was reliance on a 2,700-acre plantation. • Analogy: like being able to control only one room in a hotel. • The investors in a partnership could “readily order the on-site manager to cease cultivating their particular plot.” • However, there was no formal mechanism to effect a change on behalf of all 35 partnerships. 70 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (cont’d) • It was almost impossible to effect a change on behalf of all 35 partnerships – the investors did not even know the names of the other members of their own partnerships, – much less of the other 34 partnerships. • Stated differently, the information, organization and coordination costs were too high to exercise the legal right to effect an overall change. • Further, it was unclear whether alternative jojoba farm managers were available. 71 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (cont’d) • “[E]ven if a general partner vigorously exercised his or her rights under the partnership agreement, he or she arguably could have no impact on the investment (other than to ensure its failure by withdrawing from the larger plantation).” • The court reversed the grant of summary judgment for the defendant-promoters and remanded for factual findings on: – The necessity of participating in the 2,700 acre plantation and – The ability to affect decision making regarding that larger plantation. 72 Donald J. Weidner Koch v. Hankins (cont’d) • Court said it did not need to get to two further investor arguments: 1. that the general partnership agreement was drafted to avoid the application of the securities laws; and 2. that the investment was a security under the Silver Hills “risk capital” analysis. • There is no subsequent substantive history to this case. 73 Donald J. Weidner Steinhardt Group, Inc. v. Citicorp (3d Cir.1997) (Supp. P. 164) • Citicorp had a “severe financial crisis.” – It had lots of bad real estate loans and illiquid assets. • “The securitization transaction was thus conceived by Citicorp to remove the nonperforming assets from its financial books and replace them with cash.” • Citicorp Securities Inc. (“CSI”) made presentation to Steinhardt describing annual returns of 18% or more by investing in Bristol Limited Partnership (“LPP”). 74 Donald J. Weidner Steinhardt Group, Inc. v. Citicorp (cont’d) • Citicorp emphasized its Non-Performing Loan “Pricing Model” as an accurate means – of pricing the mortgage loans and REO (Real Estate Owned by Citicorp as a result of foreclosure) properties and – of providing Steinhardt the promised 18% or greater return on its investment. • Steinhardt alleged that Citicorp knew at the time it made the representations that several of the pricing model’s assumptions were false. 75 Donald J. Weidner Steinhardt Group, Inc. v. Citicorp (cont’d) • Steinhardt claimed that Citicorp’s Pricing Model was based on inflated valuations from brokers – who were promised that they would be hired to list the properties for sale if Citicorp was satisfied with their valuations • Steinhardt alleged various other misrepresentations and concealments. • In short, Steinhardt claimed that the cumulative effect of the misrepresentations and concealments was to fraudulently inflate the purchase price of the entire portfolio. 76 Donald J. Weidner Steinhardt Group, Inc. v. Citicorp—the transaction Citibank and CNAI Steinhardt (Citibank of North America Inc.) (investment firm) Sale of a portfolio of 3,100 M loans + 900 REO Properties Steinhardt contributed $42 million (10% of purchase price of the portfolio) to the capital of Bristol LPP. Bristol LPP GP: BGO (1% interest) To issue debt securities (nonrecourse bonds to be underwritten by CSI [Citicorp Securities Inc.]) and equity securities, in the form of partnership interests, to repay the Citibank and CNAI loans (the “bridge financing). LP #1: Steinhardt (thru its affiliate, C.B. Mtge., LPP) holds a 98.79% interest K: Ontra to service the properties. Ontra affiliate, BGO, Became GP for a 1% contribution (Ontra owns 100% of BGO) ONTRA LP #2: OLS, Inc. (an Ontra affiliate) .21% Int. Bristol LLP BGO refused Steinhardt’s demand to sue Citicorp on behalf of Bristol. 77 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (cont’d) • At the time of the initial letter agreement with Steinhardt, Citicorp was negotiating a “lock up” agreement with Ontra – under which Citicorp was to have a right of first refusal on all of Ontra’s assets and stock. • CSI was to underwrite the securities issued by LLP: – Citibank and CNAI were to bear all of the costs to issue the securities. • Although CSI determined the structure of the securitization, – Steinhardt had approval rights, and – the economic and other terms of the debt securities were not to adversely affect Steinhardt’s return on its investment. 78 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (Howey factors) • “The Howey test still predominates in investment contract analysis today.” 1. 2. 3. 4. Investment of money is clear here. Expectation of profit is clear here. Was there a common enterprise? Was the profit to be derived solely or primarily through the essential managerial efforts of a promoter or third party? 79 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (common enterprise) • The District Court said no security because no “common enterprise.” • 3d Circuit said it has applied “a horizontal commonality approach.” – “[H]orizontal commonality requires a pooling of investors’ contributions and distribution of profits and losses on a pro-rata basis among investors.” • Sounds like the 7th Circuit’s Posner in Wals v. Fox Hills a few years earlier 80 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (common enterprise) • Steinhardt argued: 1.there was horizontal commonality. 2.In the alternative, vertical commonality should be sufficient. • 3d Circuit avoided the common enterprise requirement and its commonality issue by concluding that the transaction was not “solely or primarily through the efforts of others.” 81 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (solely or primarily) • Court: “To resolve . . . whether Steinhardt’s involvement in the [LPP] was limited to that of a passive investor, we must look at the transaction as a whole, considering the arrangements . . . for the operation of the investment vehicle . . . to determine who exercised control in generating profits for the vehicle. The Limited Partnership Agreement (“LPA”), which establishes the relative powers of the partners in running the enterprise, therefore governs our inquiry.” 82 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (solely or primarily) • Steinhardt argued: It was a passive investor because it was a limited partner in a limited partnership that operated in compliance with Delaware’s Revised Uniform Limited Partnership Act (“DRULPA”). • Stated differently, Steinhardt argued they did not take part in “control” within the meaning of DRULPA. – And so should be seen as passive investors within the meaning of the securities law 83 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (the agreement) • The LPA provided that the Managing Partner could not take “Material Actions” without the consent of a “Majority of the Partners. – “Majority of the Partners” was defined as those partners holding greater than 50% of the Percentage Interests – Therefore “Steinhardt alone constitutes a ‘Majority of the Partners.’” • Even though there were two other partners • Steinhardt approved the LPP’s “interim business plan,” which Citicorp drafted and which was adopted on the formation of the LPP. • The Majority partner could propose, approve or disapprove of business plans and their modification. • The general partner could be removed without notice if it failed to use its best efforts to implement Material Action proposed by the Majority. 84 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (the “control” limitation under state law) • Court said the LPA was “carefully constructed” to give Steinhardt “significant control without possibly running afoul of” DRULPA. – “Indeed, Steinhardt has proposal and approval rights rather than more affirmative responsibilities.” • Steinhardt emphasized the following “limitation of control” language from DRULPA as it then stood: – “Except for specific rights to propose and approve or disapprove . . . the limited partners shall not take any part whatsoever in, or have any control over, the business or affairs of the partnership, nor shall the limited partners have any right or authority to act for or bind the partnership.” 85 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (on “control”) • The 3d Circuit properly rejected Steinhardt’s argument that, because it did not exercise control under DRULPA, it did not exert control for Howey purposes: DRULPA “defines control . . . solely for the purpose of limiting the liability of the limited partners to third parties—a situation not present here. This does not necessarily equate to the threshold for finding a passive investor under federal securities laws.” • In short, the ULPA at the time had a broad safe harbor for how much the LPs could do without exercising control. – Today (in Florida), LPs can exercise control without losing their limited liability. 86 Donald J. Weidner Steinhart (on “control”) • Federal law “determines whether the investor’s involvement is significant enough to place it outside the role of a passive investor.” – Steinhardt’s rights and powers under the agreement “were not nominal, but rather, were significant and, thus, directly affected the profits it received from the Partnership.” – Therfore, no “security.” • They can control all the deck chairs on the Titanic? 87 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (Supplement p. 175) • In 1994, the Venerts agreed with Country Hospitality Corporation (CHC) to develop several Country Kitchen Restaurants. • On March 29, 1995, the Venerts signed “Articles of Organization” of Huron Kitchen, LLC – An LLC is formed by filing these “Articles of Organization” – The LLC was to construct and own a Country Kitchen restaurant • An Operating Agreement was entered into in the Spring of 1995. • The Venerts solicited the Tschetters with a Business Plan for the LLC that listed the Venerts as the “Project Development Team.” • In July 1995, the LLC entered into a 15-year management agreement with CHC (“Manager”). 88 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (cont’d) • Pursuant to the outside Management Agreement, the LLC agreed not to – “interfere or involve itself with the day-to-day operations of the Restaurant, and Manager may operate the Restaurant free from interference by the Owner or representative of the Owner.” • With this outside management agreement in place, in the Fall of 1995, the Venerts sold interests in Huron Kitchens LLC to the Tschetters – The Tschetters purchased “units” in the LLC, totaling a 3/11 ownership interest in the LLC, for $101,250 • The restaurant opened in the Fall of 1995. 89 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (cont’d) • The restaurant experienced financial difficulties. • The Tschetters and others personally guaranteed bank loans to the LLC and “apparently” terminated the [outside] Manager pursuant to the Management Agreement on the ground of default. • Nevertheless, the restaurant’s difficulties continued and it closed in November, 1996. • Tschetters sue the Venerts for breach of South Dakota’s version of the Uniform Securities Act. • The trial court dismissed the Tschetters’ claims as a matter of law and the Supreme Court affirmed. 90 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (solely or primarily) • State Law in General. Rejecting the investors’ claims, the Supreme Court first said that, under S.D. law, the Tschetters, as members of an LLC, had “substantial rights and powers.” – the members of [a member-managed LLC] have management powers in proportion to their contribution to capital • this is not the universal default rule – the members of an LLC have the power to elect the managers of the LLC and – the members have the power to determine the responsibilities of the managers of the LLC 91 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (solely or primarily) • This Particular Operating Agreement. Court next said that this Operating Agreement vests management powers in the members, which included the Tschetters. • The members: – received notice of meetings – could call meetings – day-to-day decisions were made by two managers, who were required to be LLC members – members had access to all records – members could authorize loans 92 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (solely or primarily) • The members also: – could select an attorney – had the right to receive profits and distributions – could authorize incidental expenses up to a total of $12,500 – could take other routine action – could elect officers for the LLC and – could remove the LLC accountant without cause. 93 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (solely or primarily) • The majority rejected the Tschetters’ argument that the outside Management Agreement took control from them (effectively trumping the LLC’s own Operating Agreement): – “[O]ur inquiry is the Tschetters role in the Huron LLC. The fact that Huron LLC acquiesced in management powers to CHC is not determinative.” • They couldn’t control any of the deck chairs? – “The Huron LLC retained the ability to terminate the management contract if the manager failed to perform ‘any material . . . agreement . . . for a period of thirty days.’” 94 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (Majority versus Dissent) • Majority’s presumption: “Only in unusual circumstances would [a member of] a membermanaged LLC be able to argue that they must rely on the entrepreneurial efforts of others rather than on their own management skills.” • Contrast the dissent: “By the time the Tschetters received their interests in Huron LLC, their hands had effectively been tied by Venerts through the management agreement” – the management agreement governed the LLC’s only asset. – a right to cancel by declaring a default is potentially costly. 95 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (More from the Dissent) • The dissent said the inquiry can not be limited to the role the investors have within the LLC itself. • The only asset was the restaurant, and the Management Agreement locked them out of controlling that. • Even if they could cancel the Management Agreement, they were still subject to the Country Kitchen franchise agreement and would need an experienced Country Kitchen manager. – As in the jojoba farm case (Koch v. Hankins), no such person might be available. • The “undeniably significant” efforts, “those essential managerial efforts which affect the failure or success of the enterprise,” were being made outside the LLC. 96 Donald J. Weidner Tschetter v. Berven (More from the Dissent) • There should not be the same presumption against classifying LLC interests as securities that there is against classifying general partnership interests as securities. • LLCs are different from partnerships, because there is no personal liability of members. – Therefore, there is less incentive to be informed about, or take an active role in, the business. • But the members here personally guaranteed the loans 97 Donald J. Weidner

![[#SWF-809] Add support for on bind and on validate](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007337359_1-f9f0d6750e6a494ec2c19e8544db36bc-300x300.png)