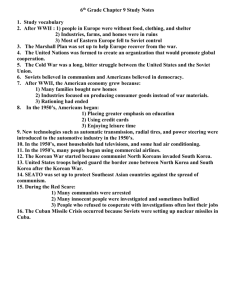

October

advertisement