Project Freak the Mighty Examples

advertisement

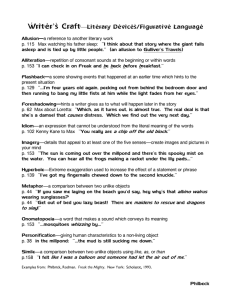

Example Cartoon Vocabulary unvanquished: a state of remaining undefeated or unconquered Link: Indiana Jones perspective: a way of seeing things Link: The sun Caption: Indiana Jones remained unvanquished in the test for the Holy Grail. 1. The team was unvanquished throughout the year and won the championship. 2. Antonio and Felix remained unvanquished in their pursuit to stay amigo brothers. 3. The unvanquished army pushed forward far behind enemy lines. Caption: From a certain perspective, the man seems to be playing hacky sack with the sun. 1. From my perspective, I only saw the back of the burglar, so I cannot make a positive identification. 2. His perspective was limited because of the torrential rain. 3. From the police officer’s perspective, both individuals seemed to be at fault because they were both speeding. Example Visual Summary Visual Summary for Freak the Mighty “Die, earthling!” “Let’s play kick teacher!” Caption for the exposition: Max’s frustration is evident in day care. Freak acts like a robot to mask his handicap. “The man is a genius for knots.” “Look what I got for Christmas!” Caption for the climax: Max’s father kidnaps Max but Freak saves the day with a squirt gun full of sulfuric acid, a.k.a. vinegar and curry powder. “What she means is you’re the spitting image of your old man.” “Magnesium! Potassium Chlorate! Strontium Nitrate!” Caption for the rising action: Max is constantly compared to his father, the antagonist who is in prison for killing Max’s mother. Caption for the rising action: Freak is riding high on Max’s shoulders as he watches the fireworks. In order to escape their conflicts, they turn to each other for friendship and become Freak the Mighty. “Kevin knew from a very young age that he wasn’t going to have a very long life.” “And that’s the truth, the whole truth. The unvanquished truth is how Freak would say it . . .” Caption for the falling action: Freak’s disease ends up being his demise, and Max (overwhelmed by grief) hides in the down under. Caption for the resolution: Max emerges from the down under, realizes that doing nothing is a drag, and overcomes his perceived mental handicap by writing the story of Freak the Mighty. Example Written Summary for the Reader’s Notebook Rodman Philbrick’s Freak the Mighty is set in rural America. This is apparent because one of the main characters, Maxwell Kane, is unable to escape his father’s reputation, of which everybody in the town seems to be clearly aware. The time period is likely the late 1980s or early 1990s because the characters are not enslaved by cell phones and social media, but Max does seem to be fond of his “Walkman” (57). Through a first-person perspective, Maxwell Kane begins the book by revealing an obviously frustrated day-care Max who lets out his anger on others, including adults. The other main character, however, seems to be a source of fascination rather than frustration. Even in Max’s early memories, he is apparently captivated by the unique Kevin, who is more commonly known as Freak, and whose genius brain (along with his other internal organs) seems to be exploding from a handicapped body that no longer grows. As the story progresses, Max and Freak quickly develop a friendship, if not a symbiotic relationship: Max needs Freak for his brain, and Freak needs Max for his physical capabilities. Consequently, the two characters embrace the name of Freak the Mighty and (inspired by the legends of King Arthur and his knights) go about on imaginary and some not-so-imaginary quests, “slaying dragons and fools” (1). During these quests, the conflicts become apparent. Ever-curious Max and Freak hear what others say about them. Max is constantly compared to his father, who is in prison for allegedly killing Max’s mother, and Max—blinded by the natural frustration that arises from this knowledge—thinks that his trouble in school, his trouble with learning in general, is due to a mental deficiency. Max continues to struggle with these thoughts (and with Freak’s challenges to be something beyond people’s expectations) throughout the book. Freak, on the other hand, often too obviously tries to mask his feelings—feelings of frustration toward a father who seemingly left his mother because of Freak’s handicap, which (as Freak knows all too well) will end his life early. Throughout the rising action, both characters are on a collision course with the inevitable: Max’s encounter with his father and Freak’s final battle with a disease, which readers later learn is a form of dwarfism with serious medical consequences. The climax for Max’s story begins whenever his father is paroled from prison. Killer Kane kidnaps Max and with what he thought was the help of Loretta and Iggy Lee (leaders of a rough neighborhood gang), hides out in an old lady’s house until he can get what he needs to escape with his son. Although Kenny adamantly maintains that he is innocent, the truth is revealed whenever Loretta tries to free the tied-up Max, who (as Killer Kane is choking Loretta) lets his father know that he remembers when Kenny choked Max’s mother to death. Consequently, Killer Kane begins to choke Max, but Freak saves the day by firing from a squirt gun what Killer Kane believes to be sulfuric acid in his eyes. It turns out that Iggy had brought the cavalry (the police) to the scene, so Killer Kane is arrested again. Freak’s story ends shortly after in a climactic scene at the hospital. Max, realizing that Freak has died, goes ballistic at the hospital, breaks things and tries to run into the medical research facility, but is finally consoled by Dr. Spivak. The falling action features a Max who, clearly devastated by the loss of his Freak, refuses to leave his room for a long time. Even after he does emerge from the “down under,” his conflict regarding his mental capacities remains unresolved until he sees Loretta again (5 &158). As mentioned, his chance meeting with Loretta helps resolve matters for Max because Loretta’s words are reminiscent of Freak’s challenge for Max before Freak dies. During one of Freak’s final conversations, he challenges Max to write the details of Freak the Mighty’s quests. Max tells Loretta that he is up to nothing, and Loretta responds by saying, “Nothing is a drag, kid. Think about it” (160). Max does think about it, and (eventually) his thoughts turn into written words on pages that feature the story of two kids who overcame incredible odds and truly did slay dragons and fools. Freak’s conflict with his disease is, sadly, resolved by his death. However, Max’s conflicts with his dad and his perceived mental deficiencies are resolved by giving birth to a Max who has escaped the evil shadow of a murderous father and who has overcome the idea that he needed Freak’s brain to think for him. Example Main Idea PLEA The main idea of Freak the Mighty is that Max’s friendship with Freak enables him to overcome his handicaps—both real and believed. Rodman Philbrick’s Freak the Mighty is a realistic fictional novel, which features Max as an unusually tall and large kid whose father was convicted for murdering Max’s mother. To add to his unfortunate circumstances, Max feels that he is learning disabled: “Writing the stuff down is not like talking . . . it’s like the pencil is a piece of spaghetti or something and it keeps slipping away” (82). Moreover, Max is naturally and emotionally scarred by his father’s actions: “They [Grim and Gram] never talk about it . . . They don’t have to because I can never forget it, no matter how much I try” (130). However, Freak teams up with Max and helps him overcome his many obstacles in life—so much so that Max eventually writes the story of Freak the Mighty (129). Max’s actions show that he, in his short life, has had to endure more heartache and trauma than most people will encounter in lifetime, but Max’s friendship with Freak—a young man who is no stranger to emotional shock—has taught him to rise above his circumstances. In fact, even after the steepest obstacle in Max’s life—Freak’s death—Max is able to face his fear of writing and put his thoughts down on paper. Example Theme PLEA The theme of Freak the Mighty is that real friends provide the motivation needed to ignore low expectations and to realize true potential. Max, the main character in Rodman Philbrick’s realistic fictional novel, naturally harbors issues with his mother’s death and father’s conviction, coupled with Freak’s physical handicap and his absentee father. These issues rise to a climactic scene whenever Max’s father abducts Max, but Freak manages to save the day with a clever bluff: “'Guess what I have for Christmas, Mr. Kane . . . This squirt gun [filled with] . . . sulfuric acid’ . . . That’s when Freak squeezes the trigger and sprays him [Killer Kane] right in the eyes” (131 & 132). Later, Max follows in Freak’s brave footsteps and overcomes his fear of writing: “So I wrote the unvanquished truth stuff down and kept on going . . . and now that I’ve written a book who knows, I might even read a few (160). Freak the Mighty’s courageous actions demonstrate that the friendship between Max and Freak enabled them to defy the expectations that people would naturally have for young boys who have experienced a lifetime of distress. Freak uses his final hours physically to rescue Max from his dragon-like father, and Max uses Freaks advice to write down the tales of Freak the Mighty, thus conquering his fear of the written word. Example: Main Idea and Theme Cartoon Vocabularies Main idea: the most important and central concept that reoccurs throughout a text Link: Max Caption: Max missed the main idea whenever Loretta Lee rubbed Freak on the head and told him about his father. 1. The main idea of Freak the Mighty is that Max’s friendship with Freak enables him to overcome his handicaps— both real and believed 2. The main idea of “Amigo Brothers” is Felix and Antonio’s friendship is strong enough to overcome a fight that placed them between each other and their dreams. 3. The main idea of “Seventh Grade” is that Mr. Bueller understands that his student, Victor, will learn more about French as the result of his crush on Teresa than he will ever learn from his teacher. Theme: the life-lesson learned from a text; the key message about life that reader’s should receive from a text Link: handicaps Caption: Max and Freak’s refusal to allow their physical and mental handicaps to overcome them helps readers understand the theme of the novel. 1. The theme of Freak the Mighty is that real friends provide the motivation needed to ignore low expectations and to realize true potential. 2. The theme of “Amigo Brothers” is friendship is more important than winning. 3. The theme of “Seventh Grade” is that romantic admiration can often provide much motivation for learning. Example Literary Devices 1. Simile: “It’s a plastic bird, light as a feather” (Philbrick 12). 2. Metaphor: “Thus television is the drug of fat heads” (19). 3. Personification: “I’ll bet we’ve gone ten miles at least, because my legs think it’s a hundred” (50). 4. Idiom: “Instead, I just shut my face and go down under” (54). 5. Hyperbole: “I watch tons of tube, but I also read tons of books” (19). 6. Suspense: “Which as it turns out, is almost true. The real deal is that she is a damsel who causes distress. Which we find out the very next day” (62). - - - end of the chapter 7. Foreshadowing: “This isn’t a pretend quest . . . This is why we came here . . . I understand this much even if I don’t understand about bionics” (52). 8. Allusion: “My mom’s name is Gwen, so sometimes I call her the Fair Guinevere” (16). 9. Onomatopoeia: “When the quarter stick of dynamite goes off, your heart thuds to a stop for a microsecond, wham” (6). 10. Alliteration: “Freak is whistling, and the cop car spotlight comes beaming around . . .” (39). 11. Repetition: “I invented games like kick-boxing and and kick-knees and kick-faces and kick-teachers . . .” (2). 12. Symbol: “A dragon is a fear of the natural world” (45). 13. First-person perspective bias/unreliability: “It was Freak himself who taught me that remembering is a great invention of the mind” (2). 14. Tone: “The little freak is staring at me bug-eyed, and he goes, ‘Oh, it talks’” (12). 15. Mood: “As we go into the Testaments, though, Freak shuts right up. It’s this big falling-apart place . . . looks sad and smells like fish and sour milk . . . and toys . . . mostly bashed up and broken” (64). 16. Direct characterization: “Grim and Gram . . . they’re my mother’s people” (1). 17. Indirect characterization: “Iggy says, ‘What if Killer Kane hears that I was messing with his kid? No thank you’” (70). Example Descriptions of Literary Devices 1. Simile: Because Max compares the ornithopter to a feather, this appeals to readers’ sense of touch. Most people have lifted feathers and know how light they are. The effect is that the ornithopter becomes a symbol for Freak: small, fragile, and seemingly flimsy things can do extraordinary things. 2. Metaphor: Freak compares television to a drug, which diminishes a person’s intellect. His point is that people become addicted to t.v., and the consequence is that time for reading is often sacrificed. The effect is that readers equate intelligence with people who read often—people such as Freak. 3. Personification: Max’s legs are given the human quality of thinking. Therefore, his legs have the ability to tell him something. The effect is that imagery is produced because most readers can connect with a time when their legs seemed to be telling them to go no farther. 4. Idiom: If taken literally, readers would think that Max’s face was like a jar that could actually be closed. However, given the context and the culture, reader’s understand that Max has decided not to talk, and the effect is that Max reveals a habit of his: bottling things up whenever he wants to speak. 5. Hyperbole: If taken literally, readers would think that the amount of television that Freak watches would weigh a ton. The point is that Freak watches t.v. frequently, so the effect is that readers understand that television is not a bad thing as long as reading time is not sacrificed. 6. Suspense: Rodman Philbrick ends this chapter by introducing a mystery. Naturally, readers become curious about who Lorretta Lee is and about how she can “cause distress.” This delay ensures that the audience will want to continue reading. 7. Foreshadowing: Because Freak makes a point of taking Max all the way out to this medical-research center, readers can infer that Freak’s medical condition will likely cause problems for him later. At this point in the novel, not much has been revealed about Freak’s physical handicap, but the result of these clues is a strong sense that his condition is really serious. 8. Allusion: Freak is referring to King Arthur’s wife, Guinevere. Most readers have at least a basic knowledge of the Arthurian legend, so the effect is that the audience thinks of knights and chivalry. 9. Onomatopoeia: The “wham” is Rodman Philbrick’s attempt to reproduce the sound of dynamite exploding. This sound device produces imagery, and the effect is that reader’s think back to the typical sounds of Independence Day. 10. Alliteration: The repetition of the “c” sounds at the beginnings of the words in this line is Philbrick’s attempt to replicate the hard sounds that fill this scene. At this point, Max and Freak need anything to save them from Tony D. This saving grace first appears in the form of sound. The effect is that these harsh sounds are actually soothing because they are basically like warning shots to the gang members. Example Visual Demonstrations of Literary Terms is light as a Caption: The ornithopter is a symbol for Freak. Both are light and seemingly flimsy but capable of extraordinary feats. Freak often refers to the Fair Gwen, which is an allusion to the Fair Guinevere, who was not only King Arthur’s queen but also the face of the utopian idea of Camelot. Freak compares television to a drug, which creates “fat heads.” This meataphor shows that the addictive nature of television causes people to sacrifice time that they should spend reading. According to Freak, reading “tons of books” helps people determine what is true and what is false. Example Leveled Questions for Freak the Mighty Level one: a question that does not require an inference 1. In Freak the Mighty, what is Freak’s first name? 2. Point: In Freak the Mighty, Freak’s first name is Kevin. Level two: a question that requires an inference and is limited to the text 1. In Freak the Mighty, why does Iggy not continue to harass Max after he discovers that Max is the son of Kenny Kane? 2. Point: In Freak the Mighty, Iggy does not continue to harass Max after he discovers that Max is the son of Kenny Kane because Iggy is scared of how Max’s father might retaliate. 3. In Freak the Mighty, why does Grim initially have very low expectations of Max? 4. Point: In Freak the Mighty, Grim initially has very low expectations of Max because Grim equates the loss of his daughter with Max, who looks like his father. Level three: a question that requires an inference but goes beyond the text to a lesson about life (thematic) 1. How do people cope with physical and mental disabilities? 2. Point: People cope with physical and mental disabilities by using their friendships to inspire them to rise above these obstacles. Tone Examples 1. “Called me Kicker for a time—this was day care the year Gram and Grim took me over . . . they were always trying to throw a hug on me, like it was a medicine I needed” (Philbrick 1). 2. “Mad Max they were calling me, or this one butthead in L.D. class called me Maxi Pad, until I persuaded him otherwise . . . Maxwell is supposed to be my real name, and sometimes I hated that worst of all. Maxwell, ugh” (3). 3. “The little freak is staring at me bug-eyed, and he goes, ‘Oh, it talks’” (12). 4. “As we go into the Testaments, though, Freak shuts right up. It’s this big falling-apart place . . . looks sad and smells like fish and sour milk . . . and toys . . . mostly bashed up and broken” (64). 5. “’How’s this for an example?’ Freak is saying. ‘Sometimes we’re nine feet tall . . . Sometimes we slay dragons and drink from the Holy Grail!’” (78). 6. “I used to think all of that spooky stuff about Friday the Thirteenth was just a pile of baloney. But now I’m getting my own personal introduction to what can happen” (80). 7. “So it’s my fault what happens next . . . this hand comes snaking out and reaches mailbox . . . and there’s something about the blind way that hand moves that’s creepy. Get out of here, I’m thinking. 8. “Maxwell Kane, your presence is requested . . . Mrs. Addison is waiting outside her office . . . and she’s trying to smile, but she’s not really a smiling kind of person, and I can tell this is serious, whatever it is” (82 & 83). 9. “He touches a lobster and it freezes, it can’t move . . . all there is in the world is this big hand and this cool breath like the wind” (100). 10. “The door has been busted in and the lock broke, and we go into the dark hallway . . .The furniture is real old and saggy . . . and an empty fishbowl . . .” (108). Example of Mood Description 1. Max’s tone is bitter and antagonistic. He feels like a piece of property that has been passed along to his grandparents. He is ready to fight anybody and everybody. The mood that is produced by this is one of sympathy for Max, and readers feel the desire to fight for him. 2. Max is disgusted with the names he has been called and with the way he has been treated. He shows that the only way he knows how to deal with conflict is to react with violence. Again, this produces a mood of sympathy for a kid who knows nothing but conflict and strife. 3. Freak responds with a condescending tone. He resents Max because Max can very easily do what Freak can’t. The only way Freak can regain his pride is to show that he is intellectually superior to Max. This builds a conflicted mood for the reader because the reader naturally senses the problems that both characters face. 4. Freak was excited about the quest to return Loretta’s purse, but the appearance of the place and the kids causes a distinct change in his attitude. The tone quickly changes to being apprehensive and dreadful. This change naturally gets the reader’s attention, and the resulting mood is one of anticipation. Readers can predict that negative circumstances are near. 5. Freak’s tone is very dramatic, confident, and triumphant. He is demanding the class’s attention so that he can deflect the bullying away from his friend Max. The subsequent mood is that readers also feel a sense of victory—the type when the underdog rises up. 6. Max’s tone is regretful and somber. Because Max is so aware of how his actions affect others, his tone shows much about his character. Reader’s begin to understand that Max is not as much of a butthead as he thinks. However, because he begins with the aforementioned tone, obvious foreshadowing occurs. The natural inference is that something regretful will occur in the chapter. 7. Again, Max’s tone is regretful and frightened. Everything about this situation screams of ill will. As mentioned before, Max is much more perceptive than he thinks, and his feelings foreshadow negative circumstances. The resulting mood is an intense, edge-of-one’s-seat feeling. Example Mood Visual Demonstration When Freak and Max enter the grounds of the tenements, the mood immediately turns sour, creepy, and depressing, which lets readers know that conflict awaits them there. Whenever Max is being bullied, Freak stands up for him and describes Freak the Mighty as being “nine feet tall,” as dragon slayers, and as partakers of the Holy Grail. The resulting mood is one of triumph and confidence. Because of Max’ s traumatic childhood, he harbors much anger, especially during day care, where he wants to kick everybody. This antagonistic tone builds a mood of sympathy for a boy who has suffered much. Example Scene in the First-Person Perspective First-person perspective: the narrator is a character in the story and uses first-person pronouns It was a typical sweltering summer day, and the Fair Gwen was busy unpacking, so I decided to try out my new ornithopter. To my dismay, as soon as flight had been achieved, an unexpected turn of events pounced on me like a ravenous hyena upon it’s helpless prey. A tree reached down and snatched my ornithopter in midflight—no chance for evasive maneuvers. But hungry hyena, I’m no brainless pachyderm roaming aimlessly on the prairie. No sir! I knew I was more than capable of retrieving my mechanical bird and am certainly able to outsmart any physical brute that tried to get the best of me. Speaking of physical brutes, just as I was about to show how superior intellect rules, my offish neighbor reached up, grabbed my ornithopter, and had the audacity to ask if I wanted it back. His tone was apparently sarcastic—a word that likely is elusive to his small vocabulary—so I decided to condescend to his level. He may be tall, but he certainly was not going to match wits with me. “Oh, it talks,” I said. He handed me the onrithopter, and his response proved my suspicions regarding the apparent thickness of his skull: “What is it, like a model airplane or something?” This butthead was quickly boring me. But since I had nothing else to do, I decided to continue the conversation, so I sit down in the wagon and say, “This is an ornithopter. An ornithopter is an experimental device propelled by flapping wings.” At first, he does not seem to be amazed, so I let the thing fly. And what does the brute do? He fetches it like a dog. Oh, this will be great, I’m thinking. I have a new puppy dog at my beckon call. I know you’re probably thinking about how terrible it is to take advantage of another person, but hey, when you’re two feet tall, having a large beast at your disposal is pretty handy. So I let Max chase it around until the flimsy thing’s propulsion unit got damaged, which really seemed to sadden the poor guy. In order to lift his spirits, I assured him that such things happen, that it can be repaired, and that I would hang out with him in the area that he appropriately terms the “down under.” Like a good Siberian husky, he pulled my sleigh—my wagon—to his house so that I could see how the beast spends its time. Example Scene in the Third-Person-Limited Perspective Third-person-limited perspective: the narrator is not a character in the story and uses third-person pronouns; the narrator only follows the thoughts and feelings of one character July, with all its fury, had turned what was already a small town into a ghost town. Nobody wanted to be outside—well, almost nobody. In one neighborhood, Kevin (a.k.a. Freak or just the little freak) had ventured out into the relentless heat in order to test out his ornithopter. The little mechanical bird was achieving Freak’s expectations until it flew too close to a maniacal tree, which seemed to purposefully snatch away Freak’s toy as if it felt the need to test Freak’s physical limitations. “Physical limitations” is a nice way of describing Freak’s condition. At around two feet tall, Freak’s external body is no longer growing, which naturally hurts his pride whenever one of his peers is able to do something that Freak can’t. And that’s exactly what his neighbor, Maxwell Kane, did. Max, a teenager who is taller and more massive than most adults, plucked the ornithopter from the tree, and said, “You want this back or what? “Oh, it talks.” Freak responded in a condescending tone. “What is it, like a model airplane or something?” asked Max. By this point, Freak was already infuriated because of his inability to physically retrieve his toy, so Max’s actions and demanding tone incited Freak’s fury to a boiling point. However, the ornithopter was now back in his possession—despite the ruthless tree’s attempt to rob Freak. Now, with his anger turning to mixed emotions, Freak decided to appease Max’s curiosity with what Freak made certain to express was his superior intellect: “This is an ornithopter. An ornithopter is defined as an experimental device propelled with by flapping wings.” Freak, with a continued effort to regain pride through the use of his impressive vocabulary, explained in detail how the ornithopter worked, and then allowed Max to see it in action. To Freak’s surprise, Max continued to retrieve the ornithopter time again like a dog fetching a stick. For the better part of an hour, both boys watch in amazement—Freak mainly amazed at Max’s willingness to chase the toy again and again—until the elastic broke. “All mechanical objects require periodic maintenance. We’ll schedule installation of a new propulsion unit as soon as the Fair Guinevere gets a replacement,” says Freak. Then Freak inquired about Max’s residence, which caused Max to promptly show him by towing Freak in the wagon straight to the “down under” as Max called it. Though surprised by this action, Freak thoroughly enjoyed the fact that he had stumbled upon a boy his age who was willing to take him places. Example Scene in the Third-Person-Omniscient Perspective Third-person-omniscient perspective: the narrator is not a character in the story and uses third-person pronouns; the narrator is able to follow the thoughts and feelings of all characters After his retreat to the down under, Max began to think that maybe he needed to keep an eye on the little freak in his neighborhood. After all, what kind of person calls another person “earthling”? Max thought, Is this an alien invasion or what? Whenever I go outside, will I see a bunch of little freaks with crutches—which are probably little death rays—pointed at me, ready to send me back to the down under for good? Beyond Max’s fence, Freak was also outside, but he had already forgotten about his encounter with his hulking beast of a neighbor. Because the Fair Gwen was busy unpacking, Kevin decided that it was as good a time as any to test out his ornithopter. But just as the toy began to fly as swiftly as any other bird in his back yard, it crashed into the one pitiful excuse for a tree present on the land. “What is it stuck on?” shouted Freak. “The few branches are as flimsy as popsicle sticks. I’ll cut this stupid thing down if I need to!” Instead, Freak found his wagon and decided to see if it would provide him enough of a boost to reach the ornithopter. “Ugh! I should have known that it would still be too high for me to reach!” By this time, Max had observed Freak’s frustration and decided that the little freak must not be an alien, or he would just take his death ray and shoot the mysterious object out of the tree. That thought supplied Max with enough bravery to venture near the tree and to grab the ornithopter. “You want this back or what? taunted Max. “Oh, it talks,” retorted Freak in an attempt to regain some pride. Freak’s ego was wounded by Max’s ability to effortlessly do what Freak could not, so he decided that the only way to save face was to show off his intellect. Consequently, Freak began to make his language as formal as the dictionary and then showed Max how amazingly the ornithopter could fly. The ornithopter became an excellent icebreaker for the two boys, so after the elastic band broke, Freak asked where Max lived. And Max showed him by towing Freak in the wagon straight over to the down under. Freak was now elated at the notion of having a peer who was willing to supplement his intelligence and imagination with the brute force needed to make many of his desires a reality. And Max, well, he was just happy that he was still alive and that the planet had not been invaded. Example Scene in the Third-Person Objective Third-person-objective point of view: the narrator is not a character in the story and uses third-person pronouns; the narrator only reveals the story through actions and dialogue—no thoughts or feelings On a sultry summer afternoon, two neighbors, Max and Kevin, had ventured outside into the heat. Kevin tested out his mechanical bird or otherwise known as an ornithopter. Max was out spying on Kevin because, earlier in the day, the two boys had an unpleasant encounter during which Kevin had pointed his crutches at Max and shouted, “Die, earthling, die!” Kevin’s play time with his ornithopter ended rather abruptly when a pathetic-looking tree invaded the air space with its equally flimsy branches. Somehow, the ornithopter became stuck among the branches, which from Kevin’s unintelligible shouting and the way his cheeks turned stop-sign red, apparently infuriated him. Consequently, Kevin tried to reach his toy by standing on a wagon. Because he boy was only a couple of feet tall and evidently suffered from a severe physical handicap, he was still unable to reach the ornithopter, which was easily within the grasp of a normal-size teenager. Max seemed to notice that the thing in the tree was easily reachable, so he braved his way across to Kevin’s yard— staying just out of the reach of Kevin’s crutches—and freed the strange object from the tree. Max then said, “Do you want this back or what?” “Oh, it talks,” Kevin replied. His tone remained hostile just as it was this morning, but not aggressive enough to scare Max back to the down under. “What is it, like a model airplane or something?” “An ornithopter is defined as an experimental device propelled by flapping wings.” Kevin continued to explain the purpose of his toy, and then he showed how it could fly just like a bird. Each time it flew, Max retrieved it like an obedient lab during a duck hunt. They perpetuated this interaction for almost an hour until the elastic band broke. Kevin then explained that his toy could be fixed and then inquired about where Max lived. Instead of responding in words, Max promptly whisked Kevin away, dragging him on his wagon like a car being towed. Kevin smiled widely as they made the trek to Max’s basement.