Developing approaches to reflective practice

advertisement

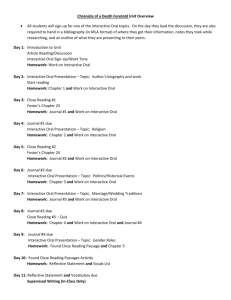

Reflective practice Session 3 – Developing approaches to reflective practice research Introduction • Welcome to the third session on reflective practice. • This session will build on the reflective practice research skills that you began to use in Session 2 with the learning journal. • We will be looking at four additional research activities for reflective and reflexive teaching – using audio and video, interviews and questionnaires, graphic representation, and peer research assistants. Using audio and video • Being observed in the classroom is an everyday event for most teachers but it is far less usual to hear or watch our own classroom performances. Yet the opportunity to see and evaluate our own teaching is invaluable. • As with all other reflective practice, when choosing to use audio or video, you should identify an area you want to know more about in your own teaching. It might be to look at the balance of teacher/student talk or you might want to know whether certain students work better in a group or individually. You do not have to record the whole lesson (unless you want to understand something over that period of time) – a ten-minute section of the lesson will yield substantial data for analysis. Video • Video recordings can be useful in showing you aspects of your classroom. For example, you might want to see how all groups work when you are involved in working with one group. The video quality simply has to show the elements you are interested in, and be able to pick up sound from the appropriate source. Remember too that you are the only audience (unless you choose otherwise) so don’t be too worried about appearing on film. • A case study about the use of video in reflective teaching is available at www.gaera.org/ger/v9n1_2012/No1_FALL_12_Pelligrino_ Gerber.pdf. Audio • Audio recordings can be useful for considering aspects of classroom talk – the students’ or your own. You might want to check, for example, whether your instructions and explanations are clear, whether students use talk to build ideas (or just dominate the conversation), and ways you respond to student talk. • If you would like to read more about talk in the classroom, a paper by Neil Mercer and Lyn Dawes is available online at www.google.co.uk/?gfe_rd=cr&ei=l8hYVMeSIrH8gfz24DoCQ&gws_rd=ssl#q=mercer+talkin+classroom. Using interviews and questionnaires • Part of the collection of evidence for reflective practice might include the views of students. • Bearing in mind a power dynamic that sometimes means students answer in ways they think you might want them to (or the opposite, of course) nevertheless, if you explain your purpose in wanting to make learning and teaching even better in your classroom, most students respond well. • Remember too that all evidence collection has an ethical dimension, as discussed in Session 2. Interviews • Appropriate questions are the key component of any interview so, once again, what exactly do you want to know about this students’ reaction to a particular classroom event and how will this information help you to action change? • ‘Good’ questions ask for extended responses (not ‘yes’ or ‘no’) and ask about one event at a time. Multiple questions (Did you find xx easy or difficult? Why? What else could there have been instead?) are impossible to answer with any thought. The standard approach is to try the questions out first with a group you will not be interviewing, so you can test for clarity and accessibility. Interviews (continued) • You do not have to have individual interviews. You can have focus groups of six to eight students. These work well so long as you are aware of any over-dominant voices which might skew data. • Interviews will need organising – who, what, where, when – and interviews with students are usually time limited to about 10–15 minutes. You will need to record the interviews and transcribe the most important responses afterwards (whole transcriptions are very time expensive). • For further discussions on interviewing, the following paper might be of interest. www.edu.plymouth.ac.uk/resined/interviews/inthome.htm Questionnaires • Questionnaires offer an immediate advantage in that they produce written responses which usually are relatively easy to analyse. • The same advice about questions applies to questionnaires. They have to be clear and unambiguous. However, the difference is that a ‘yes’/’no’ answer is actually quite helpful – too many ‘open’ questions and you will spend a very long time analysing responses. • You might also like to use the Likert Scale – a response from 1–4 indicating ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ (not five boxes or your respondents will tick the middle box). Questionnaires (continued) • Do not have too many questions – you run the danger that your respondents will either give up or tick randomly towards the end. Ten questions are more than enough. • Make the questionnaire easy to answer with underline or circle responses. • Do not offer more than one or two ‘open’ questions (which may be stem sentences, e.g. ‘I learn best when …’, or at the end of the questionnaire, e.g. ‘Anything you would like to add?’). • Give your respondents adequate time to respond. • Decide whether you really need a name (anonymous responses can be more honest). Questionnaires (continued) • Consider an online survey (e.g. surveymonkey), which will also analyse the data into graphs (you still have to analyse the results though). • Unless you have a captive audience, most questionnaires only have a 30 per cent response rate. If you are seeking opinion outside of the classroom, allow enough time to send reminder e-mails. • The following link gives more information on questionnaires. www.edu.plymouth.ac.uk/RESINED/QUESTS/index.htm Graphic representation • Put simply, this is a picture representation of a classroom, or a place where learning is taking place, at any given point. It does not call for artistic skills and a simple piece of A4 and a pencil are sufficient to produce valuable and often intriguing information. • The picture should show an event (such as reading at home) with the student, and any other information that is relevant, included in the picture. In this scenario, for example, you might ask the student to include the name of the reading materials. Graphic representation (continued) • The picture can then either be used as a prompt for the student to talk to you about their drawing, which you could record, or you can use the drawing as a starting point for reflection. – How has the student represented himself/herself? – What else have they chosen to include that might be important to consider? – If it is a classroom, where are they sitting and who else is near? – Are you in the picture? What are you doing? • This is not art therapy which is a separate skill in itself, but rather an opportunity to literally see the world as your student sees it. Reflecting on the experience of students in this way can be both powerful and revealing. Working with a peer: having a research assistant • This is a non-judgmental activity. You invite a colleague into your classroom as a research assistant – that is, you set the agenda and ask him/her to collect evidence for you. You later meet with your colleague to discuss the data and make some decisions on action. It may be that they will ask you to reciprocate. • You might, for example, ask your colleague to sit with a particular group of students and note responses to a set task. You might want your colleague to work with gifted and talented students and to report back on extension work you have set or collect evidence on students who are underperforming. • The research assistant role enables you to collect in-depth evidence in ways you might like to, but cannot in the day-to-day demands of the classroom. Peer research assistant • In order for this to work effectively, you will, as always, need to be clear about what area you want your colleague to focus on, why, and what evidence will be most useful to you. • You will also need to ‘book time’ for a meeting after the lesson so that you have time to explore the research evidence together, analyse findings and decide on actions. This activity will provide reflective opportunities for you, but also for your colleague. • Advice on observation can be found on the Learning Wales website, but it is important to remember that this is not observation by a manager, but a collegiate and invited activity. Applying reflective practice skills Activity 1 Using the learning journal template in the facilitator’s pack, please consider the scenarios on the next slide. Select one approach from those you have read about so far which would allow you to gather evidence to support reflective practice. Say why you have chosen the approach you have and what you would expect to learn from it that other strategies might not let you achieve. Scenarios 1. You have been using a new resource to teach your students. You are pleased with the outcomes generally but the students do not seem enthusiastic. 2. You have asked students to do some work involving internet research on a given topic at home. Only four students have completed the task. 3. You have been using a smartboard to teach and you are interested to know whether your impressions about the impact on students’ learning and interest levels are accurate. Approaches to reflective practice in action • In this session, you have considered using four approaches to reflective practice – all designed to gather evidence in ways useful to reflective and reflexive practice.