Pub.policy221.winter.11.wk2

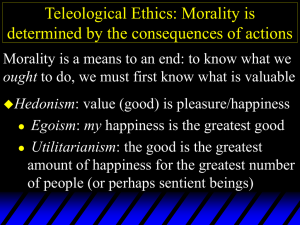

advertisement

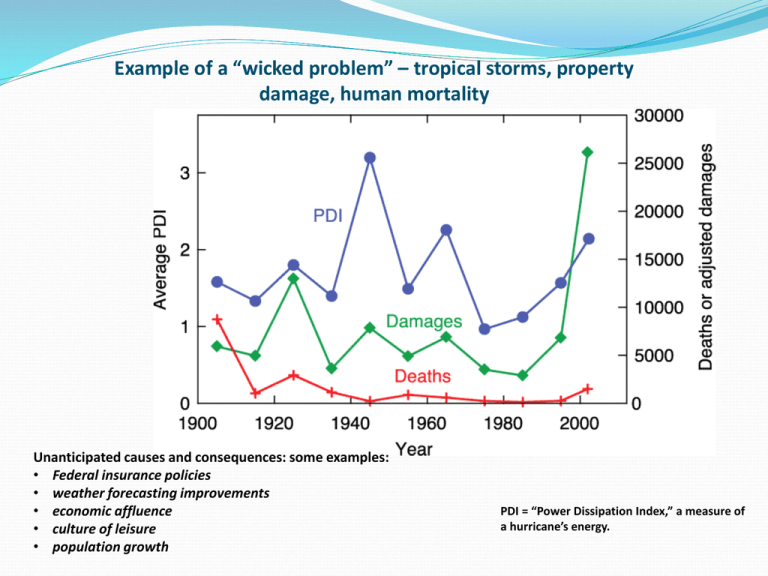

Example of a “wicked problem” – tropical storms, property damage, human mortality Unanticipated causes and consequences: some examples: • Federal insurance policies • weather forecasting improvements • economic affluence • culture of leisure • population growth PDI = “Power Dissipation Index,” a measure of a hurricane’s energy. Empirical and normative approaches to policy analysis All approaches to policy analysis – seek to explain why certain policies are established, and the consequences they bring about: Empirical approaches – draw principally from behavioral social sciences to explain why things occur and the significance we should attach to them. Normative approaches – derived principally from analytical philosophy, try – to establish what makes a policy approach “good” or “bad,” and/or right or virtuous. Approaches are usually employed in tandem! Some major empirical approaches and their significance Rational economic models – 18th Century (J.S. Mill, J. Bentham). Public policies are based on articulation of cumulative individual choices – from a normative standpoint, this approach serve as a justification (to some) of the efficacy of utilitarianism. Public choice approaches – a modern variant of rational choice based on insights from political science. Assumes people act rationally, but do so within the context of groups, not as individuals. They join coalitions of like minded individuals in order to enhance both choices, and their power in obtaining them (motives may vary – from egoism/hedonism to justice). State capacity approach – preferred policies and their achievement depend, to a large extent, on the ability of a polity to amass the resources, and administrative competence, to develop a set of policies over some social concern and then carry them out (David Apter, Samuel Huntington, Theda Skocpol). Variants of public choice Institutional rational choice – imperfect information, organizational impediments, and limits of our cognition constrain what we are able to achieve. Thus, everything we do is an effort to optimize or “satisfice” – achieving the best solutions given limits of time, money, other resources (e.g., Herbert Simon). Common experience within public sector organizations: regulatory agencies, planning agencies, business corporations. Advocacy coalition model – often, we find that practically speaking, we form coalitions not based on “like-minded” interest, but to thwart or counter-act a common opponent, and because we share a few practical aspirations in common: Common experience in legislatures and citizen-action movements: taxpayer groups and environmental interests joining together to oppose dams, nuclear power plants, or subsidies for large energy companies) - to Paul Sabatier/Hank Jenkins-Smith). Lessons from state capacity approaches The more highly-developed a polity, the stronger and more adaptable tend to be the institutions charged with making & implementing policy – and more broadlybased and – usually – flexible, are policy outcomes: e.g., To have a national health care system, you must first be sufficiently developed enough to have medical personnel who are highly-trained and equipped, and whose work can penetrate society and deliver basic needs. Without these, you cannot organize and carry-out national programs for immunization, pre-natal care, primary health care delivery, etc. – numerous exponents. Normative approaches to policy analysis Long-standing debate regarding objective status of norms in public policy: Cognitivism values have a clear, knowable, defensible foundation & are universal. Distributive justice – Society is obligated to equalize or make widely-distributed opportunities for everyone through politics: Plato, Aristotle, Montesquieu, J. Rawls. Utilitarianism – whatever accrues to the greatest pleasure for the greatest number is good policy: J. Bentham, J.S. Mill. Personalism or natural law approach – human needs, and the development of the whole person should be goal of policy: Plato, Aquinas, social psychologists such as A. Maslow and L. Kohlberg Deontic views of justice – treat others as we would have them treat us; care for others as we would care for ourselves & put yourself in another’s place in making policy: I. Kant – other advocates of the “Golden Rule.” Divine revelation/divine law – e.g., religion/so-called “eternal law” should be basis for policy (common theme in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism Hinduism, etc.) Normative approaches (con.) Non-cognitivism: values are merely preferences, “social codes” based on convention or self-interest, not universal principles. Ethical relativism – “what’s right for you is right for you.” Ethical principles that form basis of policy are culturally-shaped and not universal (various thinkers). Egoism/hedonism – prudential self-interest based on maximizing pleasure is the only value public policy should pursue: T. Hobbes, B.F. Skinner. Realism – politics and policy are the triumph of power, not justice. “The ends justify the means as viewed by the Prince:” N. Machiavelli. Social Darwinism –fierce competition for survival produces social progress and prosperity; government’s role should be minimal (“law of the jungle” – e.g., Herbert Spencer). Applying normative approaches Example – President Obama’s student financial aid policy proposal – end federal guaranteed loan program; students would borrow directly from federal government; making it easier and cheaper to borrow for college. Pell Grant maximum amounts would Personalism – the less the economic burden to get an be indexed to inflation. education, the greater the full-development of human capital. Social Darwinism – life isn’t fair; some have to work and compete harder to get an education. Those who struggle on their own and succeed are better for it, and so is society. Distributive justice- low interest government loans will equalize access by removing financial barriers – this benefits society by producing more college graduates. Utilitarianism – the greater the number of college students educated, at lower economic cost the greater the net benefit to society. Relativism – if you want to go to college, that’s your choice. Some choose not to because they don’t value higher ed. Neither is a social benefit, merely an individual choice. Government should not promote one option over the other.