Downloads - Simon Fraser University

advertisement

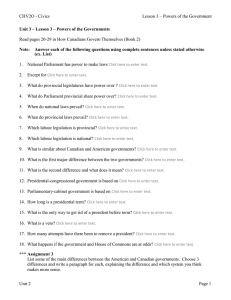

BC Health Care The Romanow Report and the state of Provincial health care Tom Koch adj. prof. Gerontology, Simon Fraser University (SFU). adj. prof. Geography (medical), UBC. bioethicist, Canadian Down syndrome Society (resource council). assoc. David Lam Center for Int. Communications, SFU. dir. Information Outreach, Ltd. http://kochworks.com Federal and Provincial perspectives Within the next year, federal and provincial elections will be fought in large part over the issue of healthcare and responsibility for it. And while there is a robust federal debate over healthcare—funding and scope—there has been no debate over provincial health initiatives since the current government’s election. Debate The lack of debate can be traced to: Lack of a strong legislative opposition. Lack of an educated and watchful press. Lack of public venues for debate and citizen participation. LHA amalgamation (Vancouver Coastal as an example). The desire to preach to the choir. The Result The most extensive contraction of health service in the province’s history, and the most expensive, has occurred without debate, with a minimum of discussion and a maximum of rancor. Summary History The Provincial Perspective The current government was elected in 2000 on the promise of an open, inclusive, consultative, transparent service that would not cut health services but would cut costs, providing healthcare more efficiently and less expensively. Public Support During the campaign, both the public and health professionals agreed on the need for change, that the system needed fixing, or at least would benefit from improvements. If we could have more for less . . . Why not? The history In April, 2002 the BC government announced major changes to the infrastructure of the provincial health care system. Rationale One goal was to restore public faith in provincial health care BC. “We can never again let the system run down to the point where people lose confidence in health care.” H. McLeod, Vancouver-Costal Health Authority interim CEO. Province Newspaper, 24 April, 2002, A4. To Build the system . . . Financial: To decrease cost by at least $550 million without a loss of service. • • • • This required: Increased efficiency, Economic sustainability, Increased user confidence, Health worker support. B.C. demographics The promise of more for less was made with full knowledge of BC’s population trends. Increases in most jurisdictions meant more service would be required in all parts of the province, and especially in its most populated, southern districts. The provincial reality Courtesy CHSPR: BC Health Atlas, 2002. The Provincial Result The result has been less for more . . . less service at a greater cost during a period of rapid population growth. There is less public confidence and worse relations between the government and the health professionals who provide bedside service. Service Summary B.C. hospital service capacities have decreased by between 8 and 12 percent overall. The closure of hospitals, ER’s, and nursing homes has increased pressure on remaining institutions. Closures may have increased both systemic costs (Lin, 2001). budget cuts Changes Resulting Removed from the BC system by 2004: • >862 acute care beds. • 9 to 12 ER’s. • >10-12 hospitals. • >1,890 long-term and extended care beds. • One or more rehabilitation centers. The “restructuring” has been a wholesale contraction. Results in patient days. Put another way, in the language of “patient days” service, this is at least 11.4 % of patient days at full capacity. At 85 % capacity the reduction is approximately 10 percent. This is well below OECD median levels. Hurrah! Opps Great: Less persons in hospital is more people at home with lessened noscomic illness. . . . if decreased patient days was accompanied by increased homecare services and support. It would be good if it did not also represent persons sent home from hospital who needed to be hospitalized, if all those who needed hospitalization received it. Communities most affected: Communities with hospitals that have been closed/downgraded: Ashcroft Delta Kaslo Summerland New Westminister Castlegar Enderby Kimberly Sanich Clearwater Ft. St. James Mission Victoria Vancouver Effect of hospital closures • Increases pressure & costs for remaining institutions. • Downloads costs of travel on patients, patient families. • Likely increased length of patient stay at referral • hospitals (Lin, 2002). • Decreased chances of survival in some health situations. • Loss of staff to BC health system. • Decreased income/livability in local/regional communities. • Decreased long-term desirability of a region. Vancouver-Coastal: Effect VGH Status 2000-2001: 662 patient days per 1000 pop. age adjusted. = 1.8 bed per 1000 pop. age-adjusted. = 2.1 beds per 1000 pop. age adjusted @ 85 percent capacity 2003 587 patient days per 1000 pop. age adjusted. = 1.6 beds per 1000 pop. age adjusted. = 1.9 beds per 1000 pop age adjusted @ 85 percent capacity. Effective results: Wait lists/wait time Wait lists for essential, non-critical surgical procedures (hip replacement, for ex.) have at least doubled. Wait times for beds have increased. Wait times in many Emergency rooms have increased. Wait time for diagnostic procedures and specialist referrals has increased. Changes: Emergency Rooms Communities with ER’s that have been eliminated or downgraded: Chemainus Delta Enderby Hope Castlegar Kaslo Mission Richmond Summerland Port Moody Greater Vancouver Effect on ER Service •Increased travel time may decrease survival rates and increase length of stay. • Travel costs downloaded on patient. • Emergency service response time decreases as distance from nearest ER increases. • Pressure on remaining ER’s increases. • ER waiting times increase. • Decreased response capability in cases of disaster or epidemic. The flaw: The Inelasticity of demand Demand is relatively inelastic. 93 percent of all hospitalizations are unavoidable (Lin et al. 2002). They are required if patient life and life quality is to be maintained. Delay may result in longer hospitalization in the end. All changes occur within the context of this relative inelasticity. Networks and the ‘domino’ effect Because demand is relatively inelastic, and service therefore mandated, closure of one institution places pressure on those remaining, and on other parts of the system. Money saved in one place must be spent in another, or downloaded to the patient. Savings are thus typically illusory. Referral Centres Impact is greatest on referral centres that receive the most complex cases and serve simultaneously as local and district hospitals. VGH, for example, serves (a) Vancouver (b) Greater Vancouver (c) Vancouver Coastal and (c ) the province at large. Fewer hospitals in outlying areas increases pressure on VGH. Downgrade of services (emergency and acute) at distant hospitals increases pressure at tertiary and higher level centres. Specialty Centers Similar problems can be seen at other provincial referral centres. For Example: G. F. Strong: Spinal Cord Injury neurological traumatic brain injury Closure of Skeleen Village, a TBA rehabilitation facility. Sick patients travel further B.C. standards in this area do not compare favorably with even those in the U.S.: 1-hour travel time to Emergency care for BC citizens. 2-hour travel time to Acute care service. Changes have increased distance to service in most areas, urban and rural. Hidden Costs The necessity of sending some patients to Alberta or U.S. medical institutions for urgent treatment is a hidden cost of the B.C. system contractions. Stories abound but no analysis of the system cost—or life cost—has been reported. Management and style The B.C. government has approached the business of health care by transforming healthcare into just another business. It isn’t, neither economically nor socially. Business/health models “Just in time” manufacturing modes do not serve in public service. Health care requires slack and redundancy if emergencies (epidemics, major accidents) are to be handled). Short-term cost-benefit accountancy is costly, and may result in diminished service. The B.C. Government argument The B.C. Government has blamed health care cost increases on the federal government and its failure to adequately fund health care and Increasing labour costs for care providers “the continued escalation of health care costs is not sustainable,” Ministry web site. Spending has Increased “In BC, we're spending over 42 per cent of the total provincial budget on health care, with $2 billion in new funding added over the past three years.” B.C. Ministry of Health web site accessed 8 May 2004. http://www.healthservices.gov.bc.ca/bchealthcare/pressure.html Federal Monies BUT federal monies for provincial health systems have increased, in part as a result of the Romanow Commission and its debates. This has been a boon unacknowledged by B.C.’s government in public or on its website. Labour Costs The government has blamed rising costs/declining services on patient-related employees: “We now spend $10.7 billion a year on health care. Of those dollars, almost 70 per cent goes to compensation for health care providers and support workers . . .the continued escalation of health care costs is not sustainable.” B.C. Ministry of Health web site accessed 8 May 2004. http://www.health services.gov.bc.ca/bchealthcare/pressure.html Increasing cost structures But among the most significant areas of cost increase have been: restructuring itself. management salaries. non-patient care salaries. advertising. Non-labor costs: restructuring. VCHA financial statements peg the cost of the restructuring in 2002-2003 at $20.2 million for VCHA alone. Similar costs presumably occurred in other Health Authorities. “Restructuring costs: In the current year, management has recorded an expense of for restructuring costs in the amount of $20.2 million. The restructuring costs consist of severance and related costs that are anticipated to result from the restructuring of the VCHA.” From: 2002/03 VCH financial statements Increased Management Costs The number of employees earning more than $75,000 a year at VCHA alone rose from 2002 to 2003 by about 47 percent. The cost was about $55 million. From: 2002/03 VCHA financial statements Non-patient care costs These are not cooks, dietitians, electricians, laundry workers, lab technicians, floor nurses, etc. They are financial analysts, risk assessment supervisors, managers, PR personnel, etc. The promise of money “going directly to the patient” is unmet. Severance—non-patient care personnel In addition, there were 34 severance agreements made between Vancouver Coastal and its non-unionized managers in 2002-3 for between 1 and 18 months compensation. An unknown but significant number of managers were on paid stress leave as well. Long-term costs Hidden as well are unconsidered but real long term costs of the restructuring to the BC economy: Loss of jobs to economy. Loss of secondary revenues. Loss of trained, stable, local population. Increased costs elsewhere in system. Loss of individuals to work force. Lack of Consultation Promises of openness and consultation have been unmet. The changes, while fundamental, have occurred without public debate, discussion, or citizen discussion. There is, however, a carefully constructed, provincial health services web page on the Internet. Public Advertising Instead, the government has used paid advertising as its principal medium for discourse. In two separate campaigns the health ministry has spent over $900 million on advertising promoting its “restructuring.” This does not include the cost of “branding” of LHA’s, web page design, etc. Branding healthcare The result is precisely that of a private corporation (Phillip Morris, perhaps) repositioning a product it wants to sell to the public. It appears to be a U.S. model of private health and private business transposed into a Canadian provincial setting. Health care overhead: U.S. The U.S. experience in private health care suggests a management overhead of at least 20 % of total cost of service. It is a minimum inevitable with privatization . . . and apparently with the B.C. government’s “business” model. Timing Timing of changes has been rapid and without thought to human consequences or long-term planning necessities. As one minister said, patient problems are the “sawdust” that accompanies any “renovation.” Clearly, changes have been rushed and therefore implemented without adequate safeguards. Assisted Living As SFU’s Charmain Spencer notes: “To date, consumer input and influence have been noticeably absent from the development of the assisted living mode. Perhaps not surprisingly, the resulting health, safety, and tenancy safeguards . . . have been minimal.” Spencer, C. 2004. Summation Promised but unfulfilled by the current “restructuring” are the following goals: Less expensive health system. More comprehensive health system. Shorter wait times for “elective” surgeries. Better labour relations. Restored public confidence. Public transparency. Outcomes The results to date have been: Waiting lists for common procedures have doubled or trebled. Service has decreased in many regions. Labour strife has increased. Costs have increased. Public confidence is diminished. Underlying assumption . . . Scarcity of resources is a limiting reality. It must be met by: rationing of services. decrease of services. increased efficiency of existing (remaining) services. Scarcity is an outcome Scarcity is typically a condition we create, an outcome and not an Inherent limit. Current policies have created scarcity, or increased it. Tom Koch: http://kochworks.com 1996) Book Titles 1990-2004 The Wreck of the William Brown: A True Tale of Overcrowded Lifeboats and Murder at Sea (Douglas & McIntyre, 2003; McGraw-Hill, 2004). Scarce Goods: Justice, Fairness, and Organ Transplantation (Praeger Pub: 2001) Age Speaks for Itself: Silent Voices of the Elderly (Praeger Pub: 2000) The Limits of Principle: Deciding Who Lives and What Dies (Praeger Pub: 1998) Second Chances: Crisis and Renewal in Our Everyday Lives (Turnerbooks: 1998) The Message is the Medium: Online Data and Public Information (Praeger Pub: Watersheds Stories of Crises and Renewal in Everyday Life (Lester Pub.: 1994) A Place in Time: Care Givers for Their Elderly (Praeger Pub: 1993) Mirrored Lives: Aging Children and Elderly Parents (Praeger Pub: 1990) The News as Myth: Fact and Context in Journalism (Greenwood Press: 1990) Journalism for the 21st Century: Electronic Libraries, Databases and the News (Praeger Pub: 1991) Creating a Cycle Efficient Toronto (Toronto City Cycling Committee) 1992 Six Islands on Two Wheels: A Cycling Guide to Hawaii (Bess Press: 1990). Selected references • Cohen, L. A. Manski, R. J. Magder, L. S. Mullen,s, D. Dental visits to hospital emergency departments by adults receiving Medicaid. J. of the American Dental Assoc. 133, 715-724. • Koch, T. 2001. Scarce Goods: Justice, Fairness, and Organ Transplantation. Westport, CT and London, UK: Praeger Books. • Lin, G. Allan, D. E. and Penning, M. J. 2002. Examining distance effects on hospitalizations using GIS: A study of three health regions in British Columbia, Canada. Environment and Planning A 34, 2037-2063. • Lowe, J. M. and Sen, A. 1996. Gravity Model Applications in health Planning: Analysis of an urban hospital Market. Journal of Regional Science 36:3, 437-461. • Mahew, L. D. Ribberd, R. W. and Hall, H. 1996. Predicting Patient flows and hospital case-mix. Environment and Planning A 18, 619-639. • Morrill, R. 1974. Efficiency and Equity of of Optimum Location Networks, Antipode 6:141-46. • Moscovice, Ira. 1999. Quality of Care Challenges for Rural Health. Minneapolis, MN: U. Minn. Rural Health Research Center, 7. • Shudd, S. 1996. The Impact of Travel on Patient Outcomes. Dissertation: Yale University. •Spencer, C. 2004. Seniors’ Housing Update 13:1. Simon Fraser University Gerontology Research Center.