LING2011 Language and Literacy 2001-2002

advertisement

Introduction to Cognitive Science:

Linguistics Segment

Lecture 1

September 15, 2005.

(2.00 p.m. – 3.50 p.m.)

Venue: Meng Wah Complex Room 324

Lecturer: Dr. A. B. Bodomo

Department of Linguistics

<abbodomo@hku.hk>

Course Outline and heuristics

Refer to Course Outline:

• course objectives

• format of teaching

• reading materials

• assignments

• study questions

2

Linguistics as Cognitive Science

• Cognitive science is a relatively new discipline that investigates the way the

human mind functions and how computers can simulate these functions. The

human mind is a complex system that receives, stores, processes and sends

out information. All this involves cognition, which refers to perceiving and

knowing.

• Language is an important part of this cognitive process of receiving, storing,

transforming and sending out information. We often hear or read information,

store what we hear or read in order to remember it, and process this

information before telling, or writing to, someone about it.

• Linguistics is the science of language, and is thus the part of cognitive

science that addresses issues of language learning, production, and

understanding. Students of cognitive science need to have a good grasp of

this central aspect of the discipline.

• To this end, in the linguistics component of this introduction to cognitive

science, we will address issues that center on the nature of language, its key

properties and components, and how it is learnt and used in various contexts.

3

Philosophy

Computer

Science

It is

the Scientific Study of the nature

and structure of human language and

A Linguist is not just a

how it is used in various contexts.

polyglot, but a thinker,

COG

specialist in the general

SCI

subject matter

of

Physiology

Linguistics

language(s).

Psychology

4

Many Approaches to Linguistics

• Diachronic/historical approaches: how languages change

over time

• Sociological approaches: how languages vary according to

different classes of speakers

• Mentalistic/cognitive approaches: an investigation of

language as a product of the mind i.e. language as a

cognitive process…

• Descartes…

• Chomsky…

• So how is reality represented through natural language? At

which levels of language can we conceptualise objects and

concepts?

5

Pronunciation:

Level of Phonetics/Phonology

WHITE DOVE /

/

baak6 gaap2

6

Word Form/ Structure:

Level of Morphology

• Two morphemes: {white} and {dove}

• Cantonese (Hong Kong Chinese):

– hoeng1 gong2 dak6 bit6 hang4 zing3 keoi1

'The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR)’

– hoeng1 gong2 wui6 ji5 zin2 laam5 zung1 sam1

‘The Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre’

7

Phrase/ Sentence Structure:

Level of Syntax

WHITE DOVE

• PS rule:

NP A + N

• Tree diagram:

NP

A

|

white

N

|

(1) Who did you see Chan with?

(2)*Who did you see Chan and?

(3) ngo5 heoi3 zung1 waan4

(4) heoi3 zung1 waan4

(5)*zung1 waan4 heoi3 ngo5

dove

8

Meaning:

Level of Semantics

What does the sign, white dove, mean?

Signifier and signified Reality, Mind, etc.

• English:

a. Chan loves you more than

Yan.

could mean:

b. Chan loves you more than

Yan loves you.

c. Chan loves you more than

Chan loves Yan.

• Cantonese:

a. me1 waa2 ?

could mean:

b. What did you say ?

c. What language ?

9

Meaning:

Level of Pragmatics

• What would white dove mean in some

specialized contexts, cultures, etc.?

• Pragmatics: meaning in context

– It’s hot!!

hou2 jit6 aa3

10

Topics in the linguistics component

•

•

•

•

•

PHONOLOGY

MORPHOLOGY

SYNTAX

SEMANTICS

LANGUAGE and LITERACY ACQUISITION

11

Introduction to Cognitive Science

Linguistics Component

Topic 1:

Phonology and Morphology

Keywords

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Phonology

phonetics

phone

phoneme

tone

stress

toneme

tonology

• morphology

• inflectional

morphology

• derivational

morphology

• morph

• morpheme

• morphophonology

• morphophoneme

13

Introduction

• Theme

– A survey of how linguistic knowledge at the level of phonology and

morphology is represented and computed in the minds of

speakers of a language.

• Objective

– an understanding of the basic terms and issues in phonology and

morphology

– an interface approach: rather than rigidly discussing these issues

from phonology, morphology, syntax and semantics, we will look

at how phonology interfaces with morphology and how syntax

interfaces with semantics.

14

Phonology

• A field of cognitive science that investigates how sound

systems of a language are represented in the minds of

speakers

• Stillings et al (1995:220) gives a concise specification of

what phonological knowledge as represented in the minds of

speakers is:

– The phonological component of a grammar consists of a

list of the words of that language, with the pronunciation

of each word given as a faithful acoustic image coupled

with direct instructions to the vocal tract about how to

produce that image, and instructions to the perceptual

system about how to recognize it.

15

Phonetics and Phonology:

A distinction

• Phonology

• Phonetics

– a science that deals

with the articulatory

and acoustic

properties of

sounds produced

by the vocal tract

– how a set of the

sounds produced by

the vocal tract are

organized into

meaningful sound

units in each

language

16

Phonetics and Phonology (cont’d)

• IPA chart (please refer to your own copy)

• For instance, given a list of sounds that can be

produced by the vocal tract, such as in the IPA chart

(Phonetics), only a set of these sounds are meaningful

in each of English, Cantonese and Dagaare

(Phonology).

17

18

Sets of meaningful sounds in

English, Cantonese, and Dagaare

These meaningful sound units are called phonemes.19

Phonemes

• Concrete sounds or phones give us the abstract

concept phoneme – a minimal meaningful sound unit

• basic units in phonology

– phoneme

– allophone

• phonemes in WHITE DOVE as conceptualised/

represented in the minds of speakers:

–/

//

//

/+/

//

//

//

/

20

Allophones

• Variants of a phoneme

• Examples:

– English:

• [p] and [ph] as in /

/ stop and /phit/ pit

– Cantonese:

• [n] and [l] as in /nei5/ and /lei5/ you

– Dagaare:

• [h] and [z] as in /

/ and /

/ yesterday

21

Minimal pairs

• Method for identifying • Examples in English, Cantonese,

and Dagaare:

phonemes - analysing

– English

minimal pairs

• /sip/ /s/, /tip/ /t/

• a minimal pair: a pair of

• /pit/ /p/, /bit/ /b/

words that are identical

except for a contrast in

– Dagaare

ONE sound .

• /

/ to enclose /l/ ;

/

/ to pull /t/

22

Suprasegmental phonemes:

Tone and Stress

• Stress

• Tone

– the amount of force

used in pronouncing a

syllable

– meaningful pitch

variations on syllables

Stress and Tone can indicate

differences in meaning among

pairs of words

23

Word stress in English

• Syllables may be stressed or unstressed in

English, and some variations of stress on syllables

of a word may cause differences in meaning.

– Teachers in this course are going to ensure an

'increase of marks for cognitive science

students.

– Teachers in this course are so kind that they will

in'crease your marks.

24

Tone in Cantonese

• Cantonese: TONES

• 6 tonemes:

– high (tone 1), high rising (2), mid level (3), low

falling (4), low rising (5), low level (6)

25

Tone in Dagaare

• Two tonemes - high and low

/

/

/ - to smell /

/ - to drink /

/

/

26

Phonological rules

• /Underlying phonological representations/

|

• Phonological rules

|

• [Phonetic representation]

27

Phonological rules in

English, Cantonese, and Dagaare

English

•/p/ [ph] / # —

•a stop is aspirated in word initial position.

•*pit but phit

Cantonese

•Final stops like /p/, /t/ and /k/ are not pronounced.

•E.g.

Dagaare

•a /d/ becomes [r] in secondary syllable position:

•*dide but [dire] ‘eating’

28

Morphology

• the field of cognitive science which studies how

knowledge about the form or internal structure of

words are represented and processed in the

minds of speakers.

• divided into two main parts, inflectional morphology

and derivational morphology

• Basic units of morphology: morpheme, allomorph

29

Morphemes

• A morpheme is a minimal distinctive unit of grammar

(Crystal 1997). A morpheme is an abstract term that must

be captured by a concrete realization, the morph – discrete

speech unit e.g. {white} {dove}

– [In morphology we represent units with braces.]

• {white} {doves}

• Free morpheme: {white} {dove} (these can stand

on their own)

• Bound morpheme: (-those that must be attached to

another morpheme e.g. {–s})

30

Morphology (cont’d.)

• inflectional morphology and derivational morphology.

• Inflectional morphology : knowledge through which

speakers of a language create several paradigms of the same

word to express various grammatical categories like number,

person, tense, aspect, case, and gender:

Number in English:

{paper} – {paper-s}

{dog} – {dog-z}

{prize} – {prize-iz}

But also:

{child} – {child-ren}

{foot} – {feet}

{sheep – sheep} : zero morph

The various plural variations are said to be

allomorphs of the same plural morpheme.

31

Examples of inflectional morphemes

(cont’d.)

• Person and number in

French:

–

–

–

–

–

–

• Aspect in Cantonese:

– {maai5}

Je {mang-e} – I eat

• ‘buy’ – {maai5-zo2}

Tu {mang-es} – You eat

• ‘has bought’

Il {mang-e} – He/she/it eat

– {wan2} ‘play’

Nous {mang-eons} – we eat

• {wan2-gan2}

Vous {mang-ez} – You (pl) eat

• ‘is playing’

Ils {mang-ent} – They eat

32

Derivational morphology

• Derivational morphology or

word formation morphology

on the other hand, is

concerned with the speaker

knowledge that underlies

processes that form new

words out of existing ones

by adding various affixes,

which are pieces of words.

• English: Causative

verbs from nouns and

adjectives

– {energy} – {energ-ize}

– {sterile} – {steril-ize}

– {penal} – {penal-ize }

33

Examples of derivational morphemes

(cont’d)

• Cantonese:

–

–

–

–

• Dagaare: agentive nouns

from verbs

{zai2} (little/small) as in:

– {di} ‘to eat’ - {di-raa} ‘eater’

{dang3 zai2} (small chair),

‘some one who can eat a lot’

{syu1 zai2} (booklet)

– {zo} ‘to run’ – {zo-raa} –

{ toei2 zai2} (small table)

‘runner’, ‘athlete’

– {

{

} ‘roam’ –

}

‘roamer’, ‘tourist’

34

Morphophonology

• While it is possible to talk of phonology and

morphology independently, in reality, knowledge

about these two areas are intertwined, and

speakers process these as such.

• Sometimes, speakers represent knowledge

about phonemes (meaningful sound units) based

on knowledge about some grammatical

environments.

35

Morphophonology

or morphophonemics, as it is known in North America

• the aspect of cognitive science that studies the classification

of phonological aspects of knowledge representation based

on knowledge about the grammatical aspects that affect

these phonological representations and vice versa.

• Morphophoneme:

– in parallel with a phoneme. While phonemes are written surrounded

by slashes / /, morphophonemes are surrounded by braces { }.

They are often written in CAPITALS (Crystal 1997).

36

Morphophonemic examples in English

• phonologically unpredictable singular – plural alternation

of words:

– Knife – knives

– Thief – thieves

– But NOT of

• Chief – *chieves (chiefs)

• The morphophoneme: {F} would then have

morphoallophones like [f] for singular and [v] for plural of

these words.

• Hence the need to emphasize their interrelationship.

37

Other examples of

morphophonological phenomena

• Word or lexical stress is a morphophonemic operation

• Example: in describing the rules of pronunciation we

often appeal to positions of the word in which the

sound is:

– aspiration in English: a voiceless stop in word initial

position is aspirated, elsewhere i.e. in word median and

word final, it is unaspirated. This is not just a phonological

rule but a morphophenemic rule.

38

Conclusion

• Phonology and morphology are two salient aspects of the tacit

knowledge of speakers of a language. It is at these levels of

mental representations that speakers capture the sounds and

structure of words and other minimal meaningful units of speech.

• An interface approach emphasizes that these two must not be

separated into watertight compartments, but must recognize that

there is an intimate interrelationship between them. This

interrelationship is explored in the cognitive area of

morphophonology.

• Morphology can also interface with syntax to give us

morphosyntax. Syntax is going to be one of the topics of

discussion in the next lecture.

39

References

• Crystal, David. 1997. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics.

Blackwell Publishers.

• Lepore, Ernest and Zenon Pylyshyn (eds). 1999. What Is

Cognitive Science. Blackwell Publishers. (especially chapters 10,

11, 12, and 13).

• Stillings, Neil and others. 1995. Cognitive Science: An Introduction.

MIT Press. (especially chapters 6).

• Trask, R. L. 1993. A Dictionary of Grammatical Terms in

Linguistics. Routledge.

• Wilson, R. and Frank C. Neil (eds) 1999. The MIT Encyclopedia of

the Cognitive Sciences. MIT Press

40

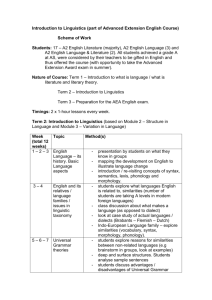

Introduction to Cognitive Science

Linguistics Component

Topic 2:

Syntax and Semantics

Keywords

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Syntax

the mental lexicon

phrase

noun phrase (NP)

verb phrase (VP)

phrase structure

sentence structure

tree diagram

•

•

•

•

•

•

constituent structure

functional structure

semantics

pragmatics

morphosyntax

syntax-semantics

interface

• ambiguity

42

Introduction: theme and objective

• Theme

– A survey of how linguistic knowledge at the level of syntax and

semantics is represented in the minds of speakers of a

language.

• Objective

– an understanding of the basic terms and issues in syntax and

semantics/pragmatics

– an interface approach: rather than rigidly discussing these

issues from phonology, morphology, syntax and semantics, we

will look at how syntax interfaces with semantics.

43

Syntax

• deals with the combination of words to form phrases and

sequences.

• What are the principles that determine ways we can or cannot

combine some words to form sentences?

• For example, why are some of these sentences correct and

others wrong?

– Who did you see Mary with?

– *Who did you see Mary and ?

– Ngo5 heoi3 zung1 waan4 ‘I’m going to Central’

– Heoi3 zung1 waan4

– * Zung1 waan4 heoi3 ngo5

44

• Syntacticians, or cognitive scientists working on syntax,

attempt to capture this knowledge by positing rules.

• Consider the situation whereby a speaker of English,

Cantonese or Dagaare wants to express the conceptual

notion of drinking water in English, Cantonese or Dagaare.

• The first step is presumably to search in a database of words

in their respective languages for the appropriate words to

express the situation.

Let us call this the mental lexicon.

45

The mental lexicon of a language

• a database containing a list of all the words in

the language, along with information about

their grammatical category, how they combine

with other words and ,of course, their meaning.

46

Simplified lexicons of English, Cantonese, and

Dagaare

(each containing words that would express the conceptual notion of a man

having drunk water )

English: ‘The man drank water.’

drank, verb, trans. ‘having ingested water through the mouth’

man, noun, count, ‘an adult male human being’

the, article, DEF.

water, noun, mass ‘a kind of liquid’

Cantonese:

• go3, CL

• naam4 jan2, noun, count ‘man’

• jam2, verb, trans. ‘drank’

• soei2, noun, mass ‘water’

47

Phrase Structure

• From the database of lexical items that would form the building blocks

of linguistic structure expressing the conceptual notion, the next step is

to group the words such that they would express the entities that take

part in the action and the action itself.

• We would refer to this group of words as phrases, a phrase being

defined as a structured group of words.

• Phrases have heads, a head of a phrase is the most important word in

the phrase. Phrases take their names after the name of their heads. So

a noun phrase (NP) is headed by a noun, verb phrase (VP) by a verb,

etc.

– ‘The man’ is an NP, ‘drank water’ is a VP. Indeed, a VP can contain

an NP, water, which just has only one item.

48

Sentence Structure

• words we need to

express a situation are

selected from our

mental lexicon.

• we have successfully

grouped them into

phrases and units to

express entities and

events.

• we are ready to put these

words to form complete

strings expressing the

conceptual situation. This

is the domain of sentence

analysis. We begin by

positing phrase structure

rules.

49

Phrase Structure rules

–

–

–

–

–

–

S

VP

NP

V

N

Art

• With these phrase structure

rules and the lexicon attached

the native speaker can form or

interpret grammatical

sentences and reject

ungrammatical ones.

NP + VP

V + NP

Art + N

drank

man, water

• (In groups of two, spend at most 3

the

minutes and come up with phrase

rules for Cantonese and Dagaare to

express the conceptual situation of a

man having drank water.)

50

A constituent structure diagram in

the form of a tree structure

S

NP

VP

NP

Art

The

N

V

N

man drank water

The first NP functions as the SUBJECT of the sentence, the verb as the

PREDICATE and the second NP as the OBJECT.

This can be represented in a functional structure diagram

51

Functional structure diagram

PRED ‘drink <SUBJECT, OBJECT>’

TENSE PAST

SUBJECT [The man]

OBJECT [water]

• This is how we represent the syntactic knowledge of

speakers of a language for basic sentences. There are

however more complex cases.

An account of the syntax alone is not enough for an adequate

interpretation of sentences that encode concepts, situations

and attitudes. We need a level of meaning to achieve this.

52

Meaning: level of semantics/

pragmatics

• What does the sign, white dove, mean?

Signifier and signified

– Reality, mind, etc

• This will be taken care of by semantics and

pragmatics

53

Semantics

• Trask (1999: 249)

• Crystal (1997: 343)

– ‘the branch of

linguistics dealing

with meanings of

words and sentences’.

– ‘a major branch of

linguistics devoted to

the study of

MEANING in

language’.

54

Meaning:

Level of Semantics

• English:

a. Chan loves you more

than Yan.

could mean:

b. Chan loves you more

than Yan loves you.

c. Chan loves you more

than Chan loves Yan.

• Cantonese:

a. me1 waa2 ?

could mean:

b. What did you say ?

c. What language ?

55

Meaning:

Level of Pragmatics

• Crystal (1997: 301)

– ‘the

study of language from the point of view of the users,

especially of the choices they make, the constraints they

encounter in using language in social interaction, and the

effects their use of language has on the other participants

in an act of communication’.

What would white dove mean in some specialised

contexts, cultures, etc.?

•What about a black tie?

56

Syntax and how it interfaces with

other components

• Morphosyntax

• The syntax-semantics interface

57

Syntax and Its Interfaces (Morphology)

• Interface with morphology

morphosyntax

– There is a close relationship between the structure

of words and the structure of sentences.

– In some languages it is even difficult to tell whether a

particular word formation is a word or a sentence:

58

Syntax and Its Interfaces (Morphology)

– Swahili (a language of East Africa):

ninakupenda

• Is a word that is made up of:

ni- naku - penda

I Tense you love

(The item –na- in this language marks tense.)

• In this language, this word structure can also stand as a

sentence, thus:

Ninakupenda

'I love you'

59

Morphosyntax (cont’d.)

In the data above, it is better to analyse this linguistic item

both in terms of its morphology and syntax, hence morphosyntax.

• Trask (1999:176)

– ‘the area of interface between morphology and syntax’.

• Crystal (1997:250-251)

– grammatical categories or properties for whose definition criteria

of morphology and syntax both apply, as in describing the

characteristics of words’

– E.g. NUMBER in nouns constitute a morphosyntactic category:

• number contrasts affect syntax (e.g. singular subject

requiring a singular verb)

• they require morphological definition (e.g. add -s for plural)

60

The Syntax-semantics Interface

• Besides studying the formal structure of sentences it is also

important to study how parts of the sentence contribute to an

interpretation of the whole sentence.

• Such is especially the case with syntactically ambiguous

sentences:

– Chan loves you more than Yan .

• Could mean:

i. Chan loves you more than Yan loves you .

ii. Chan loves you more than Chan loves Yan.

• [Class should look for more syntactic ambiguities in English,

Cantonese, and any other language]

– e.g. I hit the man with a book.

61

Conclusion

• We have briefly shown how tacit linguistic knowledge

can be represented at various levels of phonology,

morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and their

interfaces, including morphophonology,

morphosyntax, and the syntax-semantics

interrelationships.

• In the next lecture/topic, we shall look closely at how

this linguistic knowledge representation can be

formalised into an algorithm, a computational procedure

for processing this linguistic knowledge.

62

References

• Crystal, David. 1997. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics.

Blackwell Publishers.

• Lepore, Ernest and Zenon Pylyshyn (eds). 1999. What Is

Cognitive Science. Blackwell Publishers. (especially chapters 10,

11, 12, and 13).

• Stillings, Neil and others. 1995. Cognitive Science: An Introduction.

MIT Press. (especially chapters 6).

• Trask, R. L. 1993. A Dictionary of Grammatical Terms in

Linguistics. Routledge.

• Wilson, R. and Frank C. Neil (eds) 1999. The MIT Encyclopedia of

the Cognitive Sciences. MIT Press

63

- END -

64