Stephen G. CECCHETTI • Kermit L. SCHOENHOLTZ

Chapter Ten

Foreign Exchange

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

Copyright © 2011 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Introduction

• Global business includes goods, services,

stocks, bonds, etc. around the globe.

• To understand the nature of these transactions,

we must become familiar with exchange rates.

• All cross-border transactions have a buyer and

a seller that want to use their own currency.

• The exchange rate, at it most basic level, is the

tool we use to measure the price of one

currency in terms of another.

10-2

Introduction

• In this chapter we will discuss:

• How foreign exchange rates are determined,

• What accounts for their fluctuations over days,

months, years, and decade, and

• The connection of foreign exchange rates and

exchange markets.

10-3

Foreign Exchange Basics

• When you travel to other countries, the

providers of the goods and services you buy

usually want to be paid in their own currency.

• In Europe that is easier because most European

countries, at least members of the European

Monetary Union, all use euros.

• The price of one euro in dollars is called the

dollar-euro exchange rate.

10-4

The Nominal Exchange Rate

• Exchanging dollars for euros is like any other

economic transaction: you are using your

money to buy something, but in another

country.

• The price you pay for this currency is called

the nominal exchange rate, or simply the

exchange rate.

• The nominal exchange rate is the rate at which

one can exchange the currency of one country

for the currency of another country.

10-5

The Nominal Exchange Rate

• Exchange rates change every day.

• Figure 10.3 shows the dollar-euro exchange

rate from January 1999 to January 2010.

• The figure plots the number of dollars per euro

(€), which is conventional way to quote the

dollar-euro exchange rate.

10-6

The Nominal Exchange Rate

10-7

The Nominal Exchange Rate

• A decline in the value of one currency relative

to another is called a depreciation of the

currency that is falling in value.

• The rise in the value of one currency relative to

another is called an appreciation of the

currency that is rising in value.

• When one currency goes up in value relative to

another, the other currency must go down.

10-8

The Nominal Exchange Rate

• The price of the British pound is quoted in the

same ways the euro - the number of dollars that

can be exchanged for one pound (£).

• The price of Japanese yen (¥) is quoted as the

number of yen that can be purchased with one

dollar.

• Most rates tend to be quoted in the way that

yields a number larger than one.

10-9

10-10

The Real Exchange Rate

• When you visit a foreign country you want to

know how much you can buy with that

currency.

• The real exchange rate is the rate at which one

can exchange the goods and services from one

country for the goods and services from

another country.

• It is the cost of a basket of goods in one country

relative to the cost of the same basket of goods in

another country.

10-11

The Real Exchange Rate

• There is a simple relationship between the real

exchange rate and the nominal exchange rate.

• For an espresso in the U.S. and in Italy the real

exchange rate:

10-12

The Real Exchange Rate

• This tells us that one cup of Starbucks espresso

buys 1.1 cups of Italian espresso.

• The real exchange rate has no units of

measurement.

Real Exchange Rate

=

Dollar price of domestic goods

Dollar price of foreign goods

• Whenever the ratio in this equation is more

than one, foreign products will seem cheap.

10-13

The Real Exchange Rate

• The competitiveness of U.S. exports depends

on the real exchange rate.

• Appreciation of the real exchange rate makes

U.S. exports more expensive to foreigners,

reducing their competitiveness.

• Depreciation of the real exchange rate makes

U.S. exports seem cheaper to foreigners,

improving their competitiveness.

10-14

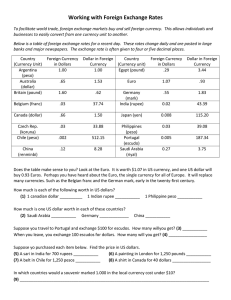

• The Wall Street Journal carries daily Foreign

Exchange column that describes events in the

markets, as well as a table reporting the most

recent nominal exchange rates between the U.S.

dollar and various foreign currencies.

• Spot rates are the rates for an immediate

exchange (subject to a two-day settlement

period).

• Forward rates are the rates at which foreign

currency dealers are willing to commit to buying

or selling a currency in the future.

10-15

10-16

Foreign Exchange Markets

• Because of its liquidity, the U.S, dollar is one

side of roughly 85 percent of the currency

transactions.

• If you want to exchange Thai baht for Japanese

Yen, you likely have to perform two

transactions:

• Thai baht for U.S. dollars and then

• U.S. dollars for Japanese yen.

• The United Kingdom is home to more than

one-third of foreign exchange trades.

10-17

Exchange Rates in the Long Run

• How are exchange rates determined?

• This section will look at the determination of

the long-run exchange rate and the forces that

drive its movement over an extended period,

such as a year or more.

10-18

The Law of One Price

• The law of one price is based on the concept of

arbitrage -- the identical products should sell

for the same price.

• We can conclude that identical goods and

services should sell for the same price

regardless of where they are sold.

• If they don’t, someone can make a profit.

10-19

The Law of One Price

• If a specific model of TV is cheaper in

Windsor, Ontario than Detroit, someone will

buy in Windsor and sell in Detroit for a profit.

• This continues until the prices are the same.

• Ignoring transportation costs and considering

foreign exchange rate, the law of one price tells

us that:

10-20

The Law of One Price

•

However, the law of one price fails almost all

of the time. Why?

1. Transportation costs can be significant, especially

for heavy items;

2. Tariffs, the taxes countries charge at their borders,

can be high;

3. Technical specifications can differ;

4. Tastes differ across countries, leading to different

pricing; and

5. Some things simply cannot be traded.

10-21

• One justification for investing abroad is that

more diversification is always better.

• It makes sense to hold a portion of your equity

portfolio in foreign stocks, as long as the stocks

in the other country do not move in lock step

with U.S. stocks.

• Evidence shows that holding foreign stocks

reduces risk without sacrificing returns, despite

the risk of exchange rate fluctuations.

10-22

Purchasing Power Parity

• The law of one price is extremely useful in

explaining the behavior of exchange rates over

long periods.

• To understand this, we can extend the law from

a single commodity to a basket of goods and

services.

• The result is the theory of purchasing power

parity (PPP), which means that one unit of U.S.

domestic currency will buy the same basket of

good and services anywhere in the world.

10-23

Purchasing Power Parity

• According to the theory of purchasing power

parity:

Dollar price of basket = Dollar price of basket

of goods in U.S.

of goods in U.K.

Dollar price of basket of goods in U.S.

1

Dollar price of basket of goods in U.K.

• Thus, purchasing power parity implies that the

real exchange rate is always equal to one.

10-24

Purchasing Power Parity

• If we just showed that a dollar does not buy the

same amount of coffee in Italy and the U.S.,

then how can this be true?

• On a given day, it is not.

• But over the long term, exchange rates do tend

to move, so this concept helps us to understand

changes that happen over years or decades.

10-25

Purchasing Power Parity

• If we quote the price of a basket of goods in the

U.K in pounds instead of dollars, then:

• Purchasing power parity implies that when

prices change in one country but not in another,

the exchange rate should change as well.

10-26

Purchasing Power Parity

• If inflation occurs in one country but not in

another, the change in prices creates an

international inflation differential.

• The currency of a country with high inflation will

depreciate.

• We can confirm this by looking at a plot of:

• The historical difference between inflation in other

countries and inflation in the U.S., and

• The percentage change in the number of units of

other countries’ currencies required to purchase one

dollar.

10-27

Purchasing Power Parity

• Figure 10.4 presents data for 71 countries

drawn from files maintained by the

International Monetary Fund.

• The solid 45-degree line is a line consistent

with the theoretical prediction of purchasing

power parity.

• On the 45-degree line, exchange rate

movements exactly equal differences in

inflation.

10-28

Purchasing Power Parity

10-29

Purchasing Power Parity

• The data in Figure 10.4 tell us that purchasing

power parity held true over the 25-year period.

• Over weeks, months, and even years, nominal

exchange rates can deviate substantially from

the levels implied by purchasing power parity.

• This means PPP does not help us explain short-term

movements.

10-30

Purchasing Power Parity

• We often hear of currencies being undervalued

or overvalued.

• When people use these terms, they have in

mind a current market rate that deviates from

what they consider to be purchasing power

parity.

• If we think one dollar should purchase one euro, the

“correct” long run exchange rate, and one dollar

purchases only 0.90 euro, it is undervalued relative

to the euro.

10-31

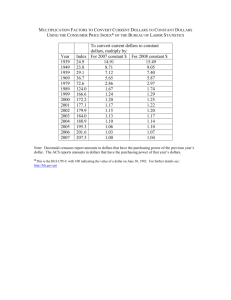

• By the end of the 20th century, the Big Mac

was available in 11 countries and was always

defined the same way.

• The Economist magazine saw this as an

opportunity.

• Using Big Mac prices as a basis for

comparison, the Big Mac index shows the

extent to which each country’s currency was

undervalued or overvalued relative to the U.S.

dollar.

10-32

An excerpt from

Table 10.5

10-33

Exchange Rates in the Short Run

• To explain short-run exchange rates, we turn to

an analysis of supply and demand for

currencies.

• Because, in the short-run, prices don’t move

much, these nominal exchange rate movements

represent changes in the real exchange rate.

• A one or two percent change in the nominal

dollar-euro exchange rate over a day or week

creates a roughly equivalent change in the real

dollar-euro exchange rate.

10-34

The Supply of Dollars

• We will use the U.S. dollar as the domestic

currency.

• This means we will discuss the number of units of

foreign currency that it takes to purchase one dollar.

• The supply of dollars slopes upward.

• The higher the price a dollar commands in the

market, the more dollars are supplied.

• The more valuable the dollar, the cheaper are

foreign-produced goods and foreign assets relative

to domestic ones in the U.S. Markets.

10-35

The Demand for Dollars

• Foreigners who want to purchase Americanmade goods, assets, or services need dollars to

do so.

• The demand curve for dollars slopes

downward.

• The cheaper the dollar--the lower the dollar-euro

exchange rate--the more attractive are U.S.

investments and the higher is the demand for dollars

with which to buy them.

10-36

• Should you try to turn a profit on changes in

the exchange rate?

• No.

• Having a good sense of what should happen in the

long run doesn’t help much in the short run.

• Looking at forward markets for major currencies

show that forward rates are virtually always within

one or two percent of current spot rates.

• The best forecast of the future exchange rate is

usually today’s exchange rate.

10-37

Equilibrium in the Market for Dollars

• The equilibrium exchange rate is the rate that

equates supply and demand for dollars.

• Because the values of all the major currencies

in the world float freely, they are determined

by market forces.

• Fluctuation in their value are the consequences of

shifts in supply or demand.

10-38

Equilibrium in the Market for Dollars

10-39

Shifts in the Supply of and Demand

for Dollars

• What shifts the supply of dollars?

• Americans wanting to purchase products from

abroad to buy foreign assets will supply dollars to

the foreign exchange market.

• Anything that increases their desire to import goods

and services from abroad, or their preference for

foreign stocks and bonds, will increase the supply

of dollars.

10-40

Shifts in the Supply of and

Demand for Dollars

A rise in the supply of dollars can be caused by:

1. An increase in Americans’ preference for

foreign goods.

2. An increase in the real interest rate on foreign

bonds (relative to U.S. bonds).

3. An increase in American wealth.

4. A decrease in the riskiness of foreign

investments relative to U.S. investments.

5. An expected depreciation of the dollar.

10-41

Shifts in the Supply of and Demand

for Dollars

• An increase in supply

leads to a depreciation

of the dollar.

• The number of euros per

dollar fall.

10-42

Shifts in the Supply of and Demand

for Dollars

To understand shifts in the demand for dollars, we can

look at the previous list from the point of view of a

foreigner:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Foreigners prefer more American-made goods.

The real yield on U.S. bonds rises (relative to foreign

bonds).

When foreigner wealth increases.

When the riskiness of American investments falls.

When the dollar is expected to appreciate.

10-43

Exchange Rate in the Short-run:

Shifts in Demand

• An increase in demand

leads to an appreciation

of the dollar.

• The number of euros per

dollar fall.

10-44

Exchange Rate in the Short-run:

Shifts in Demand

10-45

• During the crisis of 2007-2009, some non-U.S.

banks faced a sudden threat to their survival:

• When the interbank market dried up, they found it

difficult to borrow the U.S. dollars needed to fund

their dollar loans and securities.

• Banks face currency risk if they borrow in one

currency and lend in another.

• The U.S. central bank arranged a series of

extraordinary dollar swaps with 10 other

central banks.

10-46

Explaining Exchange Rate Movements

• There was a 30 percent appreciation of the

dollar relative to the euro that occurred

between January 1999 and October 2000.

• Our model allows us to conclude that the cause

was either a decrease in the dollars supplied by

Americans or an increase in the dollars

demanded by foreigners.

10-47

Explaining Exchange Rate Movements

• During this period, Americans increased their

purchases of foreign goods, increasing the

supply of dollars.

• At the same time, investment funds were

pouring into the U.S. from abroad, increasing

the demand for dollars.

• The increase in demand was greater than the

increase in supply, leading to an increase in the

exchange rate.

10-48

Explaining Exchange Rate Movements

Number of Euros per Dollar

S0

S1

E0

E1

D1

D0

Quantity of Dollars Traded

10-49

Government Policy and Foreign

Exchange Intervention

• Currency appreciation drives up the price

foreigners pay for a country’s exports and

reduces the price residents of the country pay

for imports.

• This shift in foreign versus domestic prices

hurts domestic businesses.

• Government officials can intervene in foreign

exchange markets in several ways.

10-50

Government Policy and Foreign

Exchange Intervention

• Some countries adopt a fixed exchange rate

and act to maintain it at a level of their

choosing.

• Here we will just discuss the fact that exchange

rates can be controlled if policymakers have

the resources available and are willing to take

the necessary actions.

10-51

Government Policy and Foreign

Exchange Intervention

• Policymakers will buy or sell currency in an

attempt to affect demand or supply.

• This is called foreign exchange intervention.

• Some countries hardly ever do this and some

regularly do this.

• Between 1997 and 2009, the U.S. intervened

only twice, both because of pressure from

allies.

• The Japanese are the most frequent participants

in the foreign exchange market.

10-52

• In 2009, most analysts viewed the Chinese

Yuan as undervalued.

• Many firms complained that an overly cheap Yuan

was putting Chinese producers at an unfair

advantage.

• Other governments sought to convince China

to allow their currency to appreciate.

• However, Chinese exporters preferred the weak

Yuan, which prevailed.

10-53

• As a by-product of this policy, China

accumulated a record volume of currency

reserves and became the largest holder of U.S.

Treasury debt.

• We do not know just how long China can delay

a rise of the Yuan.

10-54

Stephen G. CECCHETTI • Kermit L. SCHOENHOLTZ

End of

Chapter Ten

Foreign Exchange

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

Copyright © 2011 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.