spon-faces1

advertisement

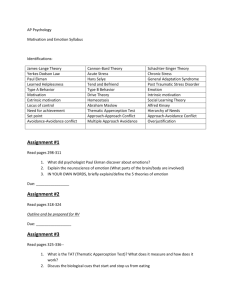

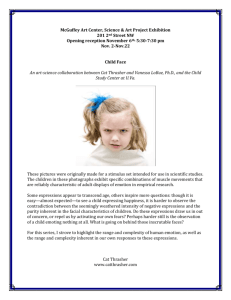

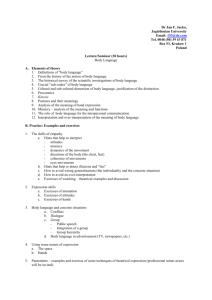

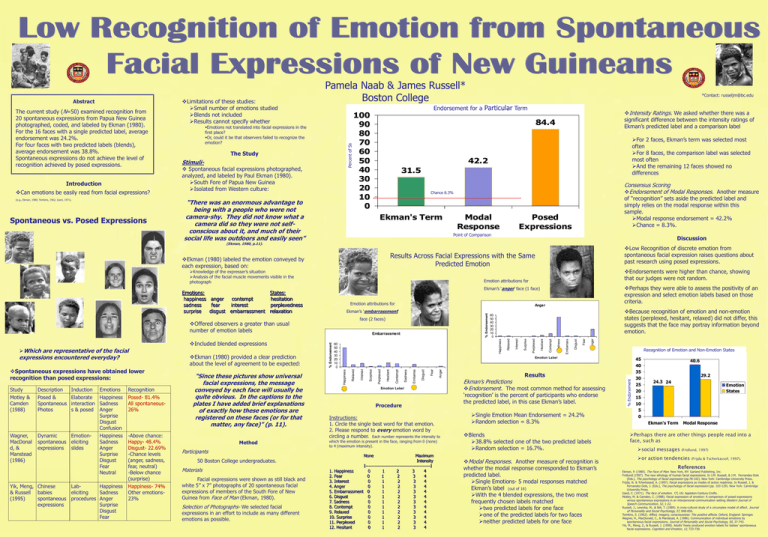

Introduction Can emotions be easily read from facial expressions? (e.g., Ekman, 1980; Tomkins, 1962; Izard, 1971). Spontaneous vs. Posed Expressions Emotions not translated into facial expressions in the first place? Or, could it be that observers failed to recognize the emotion? The Study Stimuli- Spontaneous facial expressions photographed, analyzed, and labeled by Paul Ekman (1980). South Fore of Papua New Guinea Isolated from Western culture: “There was an enormous advantage to being with a people who were not camera-shy. They did not know what a camera did so they were not selfconscious about it, and much of their social life was outdoors and easily seen” *Contact: russeljm@bc.edu Endorsement for a Particular Term 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Intensity Ratings. We asked whether there was a significant difference between the intensity ratings of Ekman’s predicted label and a comparison label 84.4 For 2 faces, Ekman’s term was selected most often For 8 faces, the comparison label was selected most often And the remaining 12 faces showed no differences 42.2 31.5 Consensus Scoring Endorsement of Modal Responses. Another measure Chance 8.3% Ekman's Term Modal Response of “recognition” sets aside the predicted label and simply relies on the modal response within this sample. Modal response endorsement = 42.2% Chance = 8.3%. Posed Expressions Point of Comparison Discussion (Ekman, 1980, p.11). Results Across Facial Expressions with the Same Predicted Emotion Ekman (1980) labeled the emotion conveyed by each expression, based on: Knowledge of the expresser’s situation Analysis of the facial muscle movements visible in the photograph Emotion attributions for Study Description Motley & Camden (1988) Posed & Elaborate Happiness Spontaneous interaction Sadness Photos s & posed Anger Surprise Disgust Confusion Posed- 81.4% All spontaneous26% Dynamic Emotionspontaneous eliciting expressions slides -Above chance: Happy- 48.4% Disgust- 22.69% -Chance levels (anger, sadness, fear, neutral) -Below chance (surprise) Happiness- 74% Other emotions23% Wagner, MacDonal d, & Manstead (1986) Induction Yik, Meng, Chinese Lab& Russell babies eliciting (1995) spontaneous procedures expressions Emotions Happiness Sadness Anger Surprise Disgust Fear Neutral Happiness Sadness Anger Surprise Disgust Fear Recognition Method Participants 50 Boston College undergraduates. Materials Facial expressions were shown as still black and white 5” x 7” photographs of 20 spontaneous facial expressions of members of the South Fore of New Guinea from Face of Man (Ekman, 1980). Selection of Photographs- We selected facial expressions in an effort to include as many different emotions as possible. Because recognition of emotion and non-emotion states (perplexed, hesitant, relaxed) did not differ, this suggests that the face may portray information beyond emotion. Anger Fear Disgust Embarrass Sadness Contempt Hesitant Perplexed Surprise Interest 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Relaxed 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Happiness Embarrassment Recognition of Emotion and Non-Emotion States 45 40 35 Anger Fear Disgust Embarras Sadness Contempt Hesitant Perplexed Surprise Interest Emotion Label Relaxed “Since these pictures show universal facial expressions, the message conveyed by each face will usually be quite obvious. In the captions to the plates I have added brief explanations of exactly how these emotions are registered on these faces (or for that matter, any face)” (p. 11). % Endorsement face (2 faces) Happiness Spontaneous expressions have obtained lower recognition than posed expressions: Ekman (1980) provided a clear prediction about the level of agreement to be expected: Anger Ekman’s ‘embarrassment’ % Endorsement expressions encountered everyday? Perhaps they were able to assess the positivity of an expression and select emotion labels based on those criteria. Ekman’s ‘anger’ face (1 face) Offered observers a greater than usual number of emotion labels Which are representative of the facial Endorsements were higher than chance, showing that our judges were not random. Emotion attributions for Emotions: States: happiness anger contempt hesitation sadness fear interest perplexedness surprise disgust embarrassment relaxation Included blended expressions Low Recognition of discrete emotion from spontaneous facial expression raises questions about past research using posed expressions. Emotion Label Procedure Instructions: 1. Circle the single best word for that emotion. 2. Please respond to every emotion word by circling a number. Each number represents the intensity to which the emotion is present in the face, ranging from 0 (none) to 4 (maximum intensity). None Maximum Intensity I------------------------------------------I 1. Happiness 0 1 2 3 4 2. Fear 0 1 2 3 4 3. Interest 0 1 2 3 4 4. Anger 0 1 2 3 4 5. Embarrassment 0 1 2 3 4 6. Disgust 0 1 2 3 4 7. Sadness 0 1 2 3 4 8. Contempt 0 1 2 3 4 9. Relaxed 0 1 2 3 4 10. Surprise 0 1 2 3 4 11. Perplexed 0 1 2 3 4 12. Hesitant 0 1 2 3 4 Results Ekman’s Predictions Endorsement. The most common method for assessing ‘recognition’ is the percent of participants who endorse the predicted label, in this case Ekman’s label. Single Emotion Mean Endorsement = 24.2% Random selection = 8.3% Blends 38.8% selected one of the two predicted labels Random selection = 16.7%. Modal Responses. Another measure of recognition is whether the modal response corresponded to Ekman’s predicted label. Single Emotions- 5 modal responses matched Ekman’s label (out of 16) With the 4 blended expressions, the two most frequently chosen labels matched two predicted labels for one face one of the predicted labels for two faces neither predicted labels for one face % Endorsement The current study (N=50) examined recognition from 20 spontaneous expressions from Papua New Guinea photographed, coded, and labeled by Ekman (1980). For the 16 faces with a single predicted label, average endorsement was 24.2%. For four faces with two predicted labels (blends), average endorsement was 38.8%. Spontaneous expressions do not achieve the level of recognition achieved by posed expressions. Limitations of these studies: Small number of emotions studied Blends not included Results cannot specify whether Percent of Ss Abstract Pamela Naab & James Russell* Boston College 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 40.6 29.2 24.3 24 Emotion States Ekman's Term Modal Response Perhaps there are other things people read into a face, such as social messages (Fridlund, 1997) or action tendencies (Frijda & Tscherkassof, 1997). References Ekman, P. (1980). The Face of Man. New York, NY: Garland Publishing, Inc. Fridlund (1997). The new ethology of human facial expressions. In J.M. Russell, & J.M. Fernandez-Dols (Eds.), The psychology of facial expression (pp.78-102). New York: Cambridge University Press. Frijda, N. & Tcherkassof, A. (1997). Facial expressions as modes of action readiness. In Russell, J. & Fernandez-Dols, J. (Eds.), The psychology of facial expression (pp. 103-129). New York: Cambridge University Press. Izard, C. (1971). The face of emotion. CT, US: Appleton-Century-Crofts. Motley, M. & Camden, C. (1988). Facial expression of emotion: A comparison of posed expressions versus spontaneous expressions in an interpersonal communication setting.Western Journal of Speech Communication, 52, 1-22. Russell, J., Lewicka, M., & Niit, T. (1989). A cross-cultural study of a circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 848-856. Tomkins, S. (1962). Affect, imagery, consciousness: The positive affects. Oxford, England: Springer. Wagner, H., MacDonald, C., & Manstead, A. (1986). Communication of individual emotions by spontaneous facial expressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 37-743. Yik, M., Meng, Z., & Russell, J. (1998). Adults’ freely produced emotion labels for babies’ spontaneous facial expressions. Cognition and Emotion, 12, 723-730.