Judicial Balancing - Barenblatt v. United States - Samuel

advertisement

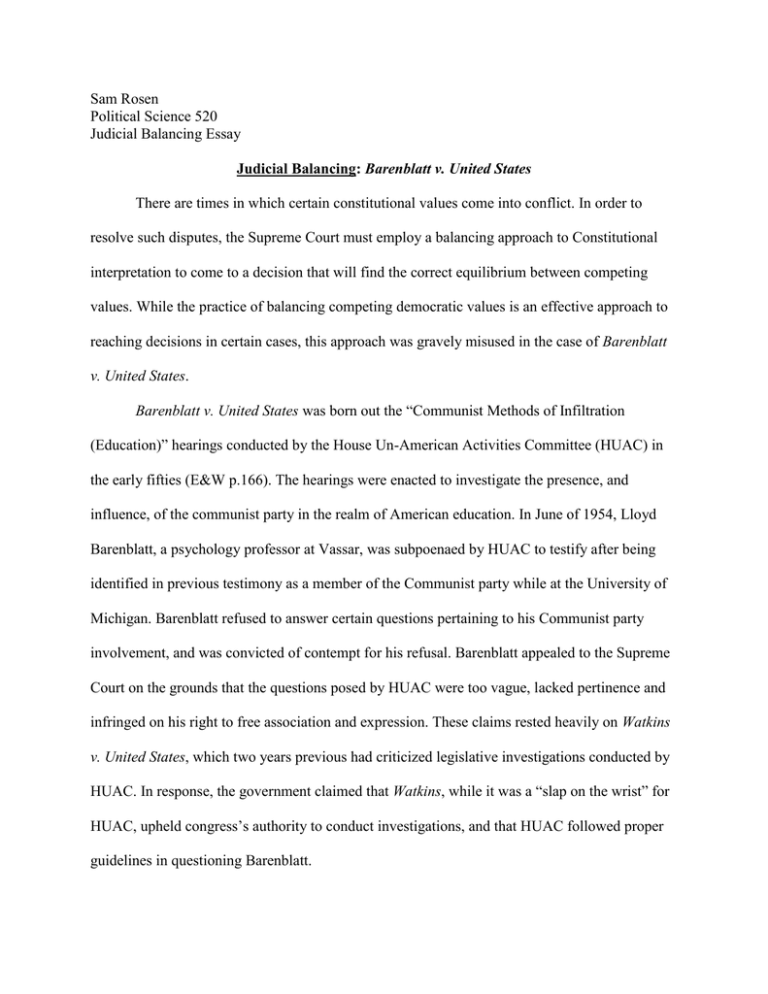

Sam Rosen Political Science 520 Judicial Balancing Essay Judicial Balancing: Barenblatt v. United States There are times in which certain constitutional values come into conflict. In order to resolve such disputes, the Supreme Court must employ a balancing approach to Constitutional interpretation to come to a decision that will find the correct equilibrium between competing values. While the practice of balancing competing democratic values is an effective approach to reaching decisions in certain cases, this approach was gravely misused in the case of Barenblatt v. United States. Barenblatt v. United States was born out the “Communist Methods of Infiltration (Education)” hearings conducted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in the early fifties (E&W p.166). The hearings were enacted to investigate the presence, and influence, of the communist party in the realm of American education. In June of 1954, Lloyd Barenblatt, a psychology professor at Vassar, was subpoenaed by HUAC to testify after being identified in previous testimony as a member of the Communist party while at the University of Michigan. Barenblatt refused to answer certain questions pertaining to his Communist party involvement, and was convicted of contempt for his refusal. Barenblatt appealed to the Supreme Court on the grounds that the questions posed by HUAC were too vague, lacked pertinence and infringed on his right to free association and expression. These claims rested heavily on Watkins v. United States, which two years previous had criticized legislative investigations conducted by HUAC. In response, the government claimed that Watkins, while it was a “slap on the wrist” for HUAC, upheld congress’s authority to conduct investigations, and that HUAC followed proper guidelines in questioning Barenblatt. Barenblatt presented a conflict between the power of congress to conduct investigations against a citizen’s right to freedom of association, expression and due process. Because the parties in dispute rest their claims on differing constitutional issues, judicial balancing is the correct approach for the case. In order to efficiently create laws, congress is afforded the authority to gather necessary information pertaining to the issues on which are being legislated (Kilbourn v. Thomson, McGrain v. Daugherty). However, Congressional investigation must observe the due process rights of the witness (Watkins). At the same time, the first amendment affords any citizen freedom of expression and association, whether friendly or adversarial to the United States, without fear of governmental penalty. This right is one of the most fundamental freedoms of our system. These two issues clearly inhibit the other’s ability to be properly exercised in this case; therefore, the court must find the correct balance between their applications in order to render a decision. Although a balancing approach was necessary for the case of Barenblatt v. United States, the court made a tremendous error in balancing the values of the case. In a five to four decision, the court sided with congress, saying that “the balance between the individual and the governmental interests here at stake must be struck in favor of the latter, and that therefore the provisions of the First Amendment have not been offended” (Barenblatt v. United States E&W p.169). In other words, the court ruled that the interests of the federal government trump the individual liberties of citizens. The court came to this decision on the basis that the purpose of the investigation was made explicitly clear to Barenblatt, quelling any question about due process. Also, the court ruled that the protections of the First Amendment are not grounds for refusal to interrogation in all circumstances, and specifically in this case because the public interest is superior to that of the individual. Careful analysis of this case shows that the court should have ruled on the side of Barenblatt. The Constitution provides the best evidence for why the scales of justice lean to the side of individual rights. There is no question that the authority to investigate is a major power of Congress. Proper laws and statutes cannot be created without intensive investigation on what is to be legislated. Investigatory power of congress is not in dispute; however, its application has historically been controversial. The power to investigate is not one of the enumerated powers given to congress, and a rigid set of guidelines was not formed for congressional investigation until the case of Kilbourn v. Thomson in 1881. Conversely, freedom of association is explicitly granted by the first amendment, “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, … or the right of the people to peaceably assemble,” (U.S. Constitution, Amd. 1). In his dissent, Justice Black refers to the language of the amendment, which clearly does not allow for these rights to abridged in any circumstance. He also points out activities of HUAC deny this fundamental freedom through rousing public contempt for witnesses. Black quotes James Madison, who said of the first ten amendments, “They will be an impenetrable bulwark against every assumption of power in the legislative or executive” (Barenblatt v. United States, Black dissent E&W p.170). Because the framers placed such emphasis in explicitly stating the rights set forth in the First Amendment, this constitutional principal should have taken precedence over an implied power such as congressional investigation; a power which is most clearly set forth by the Supreme Court itself in a case that came nearly one-hundred years after the ratification of the Constitution. The use of alternate constitutional interpretations also shows this to be true. Using a different mode of Constitutional interpretation, the court most likely would have ruled on the side of Barenblatt. An original intent approach to the case would be most beneficial to Barenblatts’s cause. The Madison quote from Black’s dissent shows that the framers intended for the Bill of Rights to serve as a limiting document on the powers given to the three branches by the Constitution, and therefore should trump conflicting interests of the three branches. A textualist approach would point to the explicit language of the First Amendment, which clearly states that “No Law” shall be made that violates an individual’s right to free exercise, and the lack of attention pertaining to congressional investigations, showing the latter to be subordinate to the former. Also, using a Stare Decisis approach, the court would find that the balance struck by the majority in Barenblatt is incompatible with the guidelines set forth by Kilbourn. The second guideline set forth by the court in Kilbourn says congressional investigations “Must deal ‘with subjects on which Congress could validly legislate’” (E&W p.157). Because the First Amendment says “Congress shall make no law” abridging an individual’s freedom of expression or association, Congress clearly cannot “validly legislate” if its investigation, or the resulting legislation, infringe on those rights. Although a balancing approach left the majority some wiggle room to side with Congress in the Barenblatt case, these other approaches firmly illustrate an error in judgment. In light of the court’s misuse of the Balancing approach to constitutional interpretation, one must ask, “Is it appropriate to allow un-elected judicial actors to use such an approach?” Regardless of such an error, the answer is yes. Like the rest of us, Supreme Court justices are human and therefore subject to the fallible nature of human reasoning. Yet, they are still the most qualified members of our federal government to hear, and settle, such disputes. Leaving such a task to the political branches runs a higher risk of trading objectivity for the wishes of a political party or constituency. Just as with judicial review, leaving judicial balancing to un-elected officials is a necessary evil that insures that the most qualified people hear such disputes, yet runs the risk of errant judgment. Regardless of Barenblatt v. United States, judicial balancing is a good practice of judicial interpretation. The Constitution is merely a framework for how the government is to properly function. Taking into consideration the existence of implied and inherent powers, which are deciphered implicitly rather than explicitly, the Constitution cannot possibly address every situation or conflict that could potentially arise. Due to the possible incongruencies in interpretation of the Constitution, especially dealing with conflicting values within, it is paramount that the Court have a means of balancing the significance of those values in order to effectively render decisions in such matters.