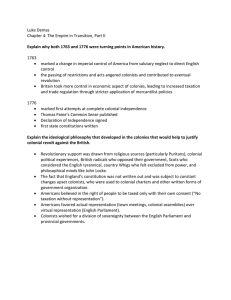

Chapter 4 Lecture PowerPoint

advertisement

CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition SPRING 2012 Brooklyn College HISTORY 3401: AMERICA TO 1877 TR8 - 3167 BRENDAN O’MALLEY, INSTRUCTOR BOMALLEY@BROOKLYN.CUNY.EDU King George III by Allan Ramsay, painted in 1762 (just two years into his rule) CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Loosening Ties: A Decentralized Empire Growing Power of Parliament: In the fifty years after the Glorious Revolution (1688), especially under the rule of King George I (1714-1727) and King George II (1727-1760), the Prime Minister of Parliament and his cabinet had become the real executives of the government rather than the king. Loose Control of Colonies: George I & II were less likely to tighten control over the colonies than their seventeenth-century predecessors since doing so might alienate the powerful merchants who made big profits with trade with the colonies. Administration of the colonies thus remained loose and inefficient. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Loosening Ties: A Decentralized Empire Nature of Colonial Governments: Few governors were talented or even competent men, while the elected colonial assemblies aggressively asserted their rights to levy taxes, approve appointments, and pass laws. Colonies Divided: Despite power assemblies and loose imperial governance, most colonists felt stronger ties to England than to the other colonies, despite having to cooperate with them on matters like trade, postal service, and road construction. Albany Plan: With the French and Indian War underway, delegates from several colonies met in Albany in 1754 to work out a plan for a “general government” to manage relations with Indians, drafted by Benjamin Franklin. Non of the colonial assemblies approved the plan— the colonies could not cooperate on so basic a need as defense. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The Struggle for the Continent Seven Years’ War: The war that broke out in North America in the 1750s and 1760s—commonly known as the French and Indian War— was the part a broader, global struggle between the French and the English known as the Seven Years’ War, which ended with a decisive English victory, leading to British control of the seas and North America. New France: By the end of the 1600s, the French had claimed almost the entirety of the North American continent’s interior: the whole Mississippi River Valley and plains stretching to the Rocky Mountains, as well as Canada to the north. The French had many Indian Allies. The Iroquois Nations: The most powerful Indian group in North America was the Iroquois Confederacy, compose of five Indian nations: the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Oneida. Founded as a defensive alliance, it controlled much of upstate New York and the Ohio River Valley. It astutely played the French and English off of each other and traded with both. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The Struggle for the Continent Anglo-French Conflicts: In the 80 years after the Glorious Revolution (1688), France and England entered into a series of wars triggered by imperial rivalry: King William’sWar (1689-1697), Queen Anne’s War (1701-1713), and King George’s War (1744-1748). Queen Anne’s War resulted in the English obtaining Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. In 1749, after King George’s War, the Iroquois granted English merchants permission to enter the interior, heightening tensions with the French. Fort Necessity: In 1754, the governor of Virginia sent a militia under the command of a young colonel named George Washington (1732-1799) to attack a French outpost on the site of what is now Pittsburgh. The detachment’s failed attack led to a counterattack of a crude stockade thrown up by Washington’s men by the French. Nearly a third of the Virginians had been killed when Washington surrendered. This was the first battle of the “French and Indian War.” CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The Struggle for the Continent: The Great War for Empire The Three Phases: The conflict went through three distinct phases: 1) 1754 – 1756: North American conflict only with all Indian tribes except the Iroquois aligned with the French. Disastrous for the English. 2) 1756 – 1758: Seven Years’ War begins with outbreak of fighting in West Indies, Europe, and India, although North America remains the primary theater. In 1757, William Pitt, the young Secretary of State back in London, takes direct control of war (it previously had been run by colonial authorities). British authorities “impressed” colonists as soldiers aand confiscated supplies from civilians, making the war effort unpopular. 3) 1758 – 1760: Pitt relaxes measures that were obnoxious to the colonists by putting the assemblies in charge for recruitment of soldiers and having farmers reimbursed for supplies taken. In 1758, the English saw a turnaround, capturing the Fortress of Louisburg in Nova Scotia and Fort Duquesne in what is now Pennsylvania. In 1759, Quebec fell, and in 1760, the French army surrendered in Montreal. A formal peace was settled in 1763. Benjamin West, The Death of General Wolfe, ca. 1771 Wolfe, a young British general in the French and Indian War. Wolfe was fatally wounded during the Siege of Quebec in 1759. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The Struggle for the Continent: The Great War for Empire Germ Warfare An early practitioner of germ warfare was the new commander of British and colonial forces in 1757, Lord Jeffrey Amherst (1717-1797). After the massacre of surrendered British and colonial troops at Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George in upstate New York in August 1757 (a crucial scene in James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans), Amherst invited to a peace talk and were given the “gift” of blankets, which had been infected with smallpox. The disease soon broke out among the Delaware, although it is hard to determine whether or not the blankets were the source. In any case, spreading the disease among the Indians was unquestionably Amherst’s intention. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The Struggle for the Continent: The Great War for Empire Peace of Paris: The conflict came to a formal end with the Peace of Paris in 1763. The treaty greatly expanded British influence in the world and North America especially: France ceded to England some of its West Indian islands (but not Haiti), most colonies in Canada and India, and claims to land east of the Mississippi. France ceded New Orleans and all lands west of the Mississippi to Spain. Debt and Resentment: The French and Indian War increased British debt significantly and at the same time caused resentment toward the colonists, who had been militarily inept, had contributed so little to the cost of the war even though it was for their own defense, and had even sold some supplies to the French. Many British leaders saw this as an opportunity to reorganize the empire and give London increased control of the colonies. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The Struggle for the Continent: The Great War for Empire Colonists’ Reaction: The war was the first time the colonies had to come together against a common foe, the 1758 return of colonial authority of impressment made others view British interference in local affairs as illegitimate. Indians’ Reaction: The British victory was disastrous for pro-French tribes of the Ohio Valley. It was only marginally better for the pro-English Iroquois Confederacy, whose passivity the English viewed as duplicitous, leading to a disintegration of Indian/English relations. Furthermore, the removal of the French from the scene left the Iroquois and other Indians without two imperial powers to play off of each other—only the British were left. Pontiac Rebellion: With the defeat of the French, English settlers began to move into the Ohio River Valley. The region’ Indian tribes struck back, raiding areas of settlement, killing hundreds of solders and frontiersmen, and pushing the line of settlement back. British authorities drew up the Proclamation of 1763 in response, forbidding settlement beyond the Appalachians. The British Colonies in 1763 CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The New Imperialism: Burdens of Empire Need for Revenue: The British government was deeply in debt and thus sought new means to raise revenue. Many in Parliament thought a direct tax of colonists was the only solution. King George III: During this difficult period, the British had the bad luck of having King George III (r. 1760-1820) take the throne. He had two unfortunate qualities: 1) He was interested in reasserting the power of the monarchy against Parliament, and removed a relatively stable ruling coalition of Whigs that governed most of the 1700s, replacing them with ministers who on average did not last more than two years. 2) The king had bouts of insanity and also has a immature and insecure personality, which contributed to the political instability. • George Grenville (1712 – 1770): He became prime minister in 1763 and shared the opinion the colonists had to pay for their own defense. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The New Imperialism: Battles over Trade and Taxes 1764 Sugar Act: Raised taxes on sugar while lowering it on molasses (it had been twice as much previously, but had never been collected). The act also created a Vice Admiralty court to enforce laws and prosecute smuggling. 1764 Currency Act: Eliminated the colonial assembly’s ability to issue paper money, potentially constricting colonial economies. 1765 Mutiny or Quartering Act: Parliament passed this act which requires colonists to help provision and maintain the army after colonial assemblies refused to do so. 1765 Stamp Act: Imposed an imperial tax on every printed document in the colonies: newspapers, almanacs, pamphlets, deeds, wills, contracts, licenses, and even dice. This quickly became the most hated of all of Grenville’s taxes as it interfered with almost every daily transaction. Designs for Stamp Act stamps Examples of how some colonial newspapers responded to the Stamp Act. Note the skull and crossbones in the place where the stamp was to be affixed (note the day of publication is also Halloween!). CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The New Imperialism: Battles over Trade and Taxes Internal Resistance to Taxes: Some colonists still harbored more resentment toward each other than toward imperial authorities. Paxton Boys: The Paxton Boys in Pennsylvania were armed frontiersmen who marched on Philadelphia in 1763 to demand tax relief and financial support for their defense against Indians. The “Regulators”: In 1771, small upcountry North Carolina farmers revolted against the high taxes collected by local sheriffs. Their revolt was put down by a militia sent from the wealthier eastern part of the colony. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition The New Imperialism: Battles over Trade and Taxes More Revenue Collection: By 1765, imperial officials were collecting ten times as much revenue as they had been two years before. New Taxes Unify the Colonists: Grenville’s taxes did more to rally the colonists together than anything they could have done themselves. They came together more readily to face an external threat. Political Implications vs. Economic Ones: Ultimately, the economic hardships posed by the new taxes were relatively slight. What really inflamed the colonists were the political implications: that Parliament had the right to tax the colonists directly and supersede the colonial assemblies. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Stamp Act Crisis Unifying the Colonies: The Sugar Act of 1764 had only affected the New New England merchants, but the Stamp Act affected everyone. A Disturbing Precedent: Past taxes and duties seemed to only regulate commerce. The new ones only seemed to have the purpose of raising revenue while circumventing the authority of the colonial assembly. Virginia Resolves: In May 1765, Patrick Henry of the Virginia House of Burgesses made a dramatic speech that predicted that the tyrannical George III might lose his head if the monarch stayed on the current course. Henry set forth several resolutions that declared that Americans had the same rights as the British, and especially the right to be taxed only by their own elected representatives; that they should not pay taxes that the House of Burgesses had not approved, and that anyone saying Parliament had the right to impose taxes on Virginia should be declared an enemy of the colony. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Stamp Act Crisis Stamp Act Congress: James Otis of Massachusetts proposed an idea of creating a colonial congress to formulate and coordinate action against the Stamp Act. The Stamp Act Congress met in Oct. 1765 in New York. Stamp Act Officials Terrorized: In Boston and other cities, tax collectors were terrorized by newly organized groups like the Sons of Liberty in Boston, who broke into their homes and burned the stamps. Repeal: In March 1766, the new prime minister who had replaced Grenville, the Marquis of Rockingham, bowed to pressure from English merchants who complained of a colonial boycott on manufactured items imported from England. He thus passed a repeal of the Stamp Act. Declaratory Act: While the colonists celebrated the repeal of the Stamp Act, a new act confirmed Parliament’s authority over the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” Most colonists did not notice this sinister wording. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Townshend Program Rockingham Dismissed: The king dismissed Rockingham because his backing down on the Stamp Act proved unpopular in England. Pitt Back in Office: The aged William Pitt replaced Rockingham, but his impaired mental condition meant that the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Charles Townshend, took over much of the governing of affairs. Mutiny Act: Colonists hated the idea of London mandating that they were responsible for the upkeep of troops. Massachusetts and New York Assemblies refused to vote on providing the mandated supplies. Townshend then targeted New York by disbanding its assembly, isolating it. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Townshend Program Townshend Duties: Townshend also had a tax passed on imported goods from England, thinking that such a tax on “external” goods would not inflame colonial sentiment. The goods included lead, paint, paper, and tea. These taxes and the suspension of New York’s assembly only managed to infuriated colonists further. Nonimportation Agreements: Townshend established a board of customs commissioners with its headquarters in Boston. These officials virtually shut down smuggling in and out of Boston, although it continued in other ports. Boston merchants organized a boycott with New York and Philadelphia merchants of the goods subject to the Townshend taxes with nonimportations agreements. American “homespun” garments and other American-made products became fashionable. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Boston Massacre Rebellious Boston: New customs officials were so harassed in Boston that British authorities sent four regiments to protect them. When off duty, these poorly paid soldiers often competed with the local workforce for menial jobs. March 5, 1770: A crowd of dockworkers and “Liberty Boys” began throwing snowballs and rocks at a detachment of soliders guarding the Customs House. In a scuffle, shots were fired and five colonists died. This murky, confusing incident that resulted from confusion and panic played into propagandists’ hands, leading to a pamphlet entitled, Innocent Blood Crying to God from the Streets of Boston. The Trial: The soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter, not murder, by a jury of colonists, but publications and newspapers convinced readers that the soldiers were guilty of official murder. “Committees of Correspondence”: In 1772, Samuel Adams proposed the creation of a “committees of correspondence” in Boston to publicize grievances against George III. Other colonies imitated Massachusetts lead, leading to a network of intercolonial organizations propagating political dissent. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Boston Massacre Engraving by Paul Revere, 1770. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Philosophy of Revolt Sources of Revolution Ideology: The years immediately following the Boston Massacre were relatively calm, but ideological challenges to British authority had become firmly entrenched. “Court vs. Country”: Rural British political writers in the early 1700s in journals like The Spectator complained that too much power had concentrated in the hands of London politicians and bankers. These writings were enormously influential among rural Americans even though they were seen as fringe and eccentric in England. “No Taxation without Representation”: The colonists became more and more insistent that they could not be taxed without the approval of their own assemblies—a foreign idea to the English—leading to the famous phrase, “Not taxation without Representation.” CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Philosophy of Revolt “Virtual” and “Actual” Representation: In England, members of parliament were viewed as representing the whole nation, not just a specific locality. While elected from specific geographical locales, parliament members in theory represented Ireland and the colonies through “virtual representation.” Americans, on the other hand, believed that since they had no directly elected representative sin Parliament, they were not represented. Sovereignty Debated: Americans were asking for a division of sovereignty between the colonial assemblies and Parliament, which the British viewed as absurd. To the British mind, their could only be one single source of power. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: Sites of Resistance Political Importance of Colonial Taverns: Taverns became an important place for the exchange of revolutionary ideas and literature. Boston had one of liveliest tavern cultures of any colonial city, so it is not surprising that it was a center of early revolutionary excitement. Newspapers would be read allowed so that the illiterate could hear and understand the news. The King’s increasing irate speeches would be read, too. Stirrings of Revolt: The Tea Excitement Tea Act of 1773: With the British East India Company on the verge of financial collapse, Parliament passed a law allowing the Company sell off large stocks of tea that it could not sell in England in the colonies without paying the usual taxes. Merchants saw this as a big unfair advantage, making it possible for the Company to undersell colonial merchants and gain a monopoly on tea. The act angered an influential constituency—the colonial merchants—and revived anger about “taxation without representation.” Lord North thought the colonists would welcome lower prices on tea, but the act generated sympathy for colonial merchants on political grounds. In the last weeks of 1773, the Company’s cargoes of tea were not allowed to land in Philadelphia and New York. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Tea Excitement Daughters of Liberty: The tea excitement entered the general society and culture at a level not seen since the Stamp Act protest. A patriotic women’s organization, the Daughters of Liberty, formed to encourage the boycotting of tea and other imported goods. Women would make “homespun” garments and wear them proudly, doing away with imported British finery. The Boston Tea Party: On December 16, 1773, three companies of fifty men masquerading as Mohawk Indians went aboard three ships, broke open the tea chests, and threw them into the harbor. As the new spread, colonists in other seaports performed similar acts of resistance. The tradition of “white Indians” committing subversive acts against new laws was not a new one—it had been practiced for decades. The Coercive Acts and the Their Consequences: In response to the Tea Party, Parliament passed for acts collectively know as the “Coercive Acts,” also known as the “Intolerable Acts.” These acts shut down the Port of Boston for trade, reduced the selfgovernment of the Massachusetts colony, permitted British officers accused of crimes to be tried elsewhere, and made colonists provide for troops stationed there. Rather than isolating Boston, great sympathy and further boycotts spread throughout the colonies. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Stirrings of Revolt: The Tea Excitement (1789 engraving) CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Cooperation and War: New Sources of Authority Committees of Correspondence:Virginia formed the first committee of correspondence thought sought to reach out and coordinate its activities with those in other colonies. When the Virginia colonial assembly was dissolved in 1774, a committee of correspondence met in a tavern, condemned the Coercive Acts, and called for a Continental Congress. The First Continental Congress: Convening in September 1774 in Philadelphia, all colonies sent delegates except for Georgia. They made five decisions: 1) Rejected a plan for colonial union under British authority; 2) Endorsed a relatively modest set of grievances; 3) made a plan for military preparations for possible attacks by British troops in Boston; 4) they agreed on a series of boycotts and formed the Continental Association to enforce them; 5) they agreed to meet the following spring. Lord North’s Conciliatory Propositions: In early 1775, the prime minister, Lord North proposed allowing the colonial assemblies to vote on taxes issued by Parliament. But by the time word arrived in North America, the first shots had been fired. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition Cooperation and War: Lexington and Concord Minutemen: The colonists had a longstanding tradition of “minutemen” to respond to Indian attack. They received some training, but were not professional soldiers in the way that the British were. General Thomas Gage: He received orders to arrest colonial leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock, known to be around Lexington, and seize a large supply of gunpowder the minutemen were keeping in Concord. On April 18, 1775, he sent a detachment of 1,000 men out in the evening, hoping to surprise the colonists. Rides of Revere and Dawes: Paul Revere and William Dawes rode ahead of the British troops and alerted the colonists about their march. First Shots Fired: When the redcoats arrived in Lexington, they found a few dozen minutemen lined up to face them. Shots were fired and eight minutemen were killed. When the British moved to Concord, they found the powder had been moved. On their march back to Boston, the troops were shot at guerilla-style. CHAPTER FOUR The Empire in Transition