Moral and Social Philosophy - Faith and the Modern World

advertisement

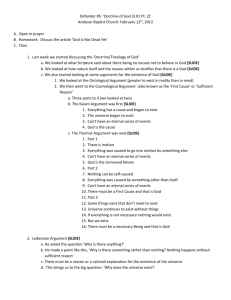

MSP 1 Wednesday Classes. Tutor: Howard Taylor (University Chaplain) Also teaches here: – 1/2 of MSP 2, 1/3 of MSP 3. – Philosophy of Science and Religion. – Takes Sunday Campus service. Term time only. Also Visiting lecturer: • `International Christian College’. • Edinburgh University Open Learning Department. Previously: – Parish Minister in West of Scotland - 17 years. – Author of several small books/booklets. – 16 years in Malawi, Africa: • Minister, Theology lecturer, African Language teacher. • Maths and Physics lecturer: University of Malawi. – Graduate of: Nottingham, Edinburgh and Aberdeen Universities. • Married with three grown up sons and two grandsons and two granddaughters. Three main Subjects for MSP1 - Wednesday Classes 1. Arguments for and against belief in God – – – – Do we need an argument? Can there be arguments against belief in God? Fundamental Mysteries. World Views - Atheism, Deism, Pantheism, Theism, Christian Theism. – Three arguments and another: 1. Cosmological Argument - for and against. 2. Design or Teleological Argument - for and against. 3. Argument from religious/spiritual experience - for and against. 4. The argument from the objective reality of morality - which is the second subject for MSP1 Three main Subjects - continued for MSP1 (Wednesdays) The Case for the Objective Validity of Morality. 2. Subjectivist and Objectivist Ethics. C. S. Lewis’s argument for the objective validity of morality. Nietzche rejects morality’s objective validity. Three main subjects for MSP1 (Wednesday classes) 3. The Problem of Evil: – for the atheist; • Atheism is the belief that there is no God. – for the theist; • Theism is the belief that God exists. – for the pantheist; • Pantheism is the belief that everything is part of God - God being the spiritual dimension of the physical world. Recommended reading: • Questions that Matter. Ed Miller. – Pages: 222 - 333, 43 - 44. • Philosophy: Popkin and Stroll. – Pages: 204- 210, 176 - 194, 52-54, 25-30. • Mere Christianity: C. S. Lewis. • Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future…: Nietzche. • The tutor does his best to be fair to all views religious and non-religious. • However in the interests of honesty he will explain what he believes. • Although the tutor has his own religious convictions, the assessment of essays and tutorials will not be affected by a student's own different convictions. • Knowledge of the subject and good argument are all important for assessment. • Holding the same beliefs as, or different beliefs from, the tutor will not be relevant for module assessment. Argument in favour of materialism. Science has successfully answered many questions about the world. One day it will be able to answer all questions. Question: Are the mysteries getting less or more? Leibniz’s argument against materialism. Thoughts cannot be material. Thoughts affect the physical world. Therefore the physical world needs more than physical science to understand it’s behaviour. Why are thoughts not material? Leibniz’s mill or mountain. Physical processes just exist – they are not true or false. Thoughts are true or false. Therefore thoughts are not just material. (See Bertrand Russell quote in next slide.) But thoughts do affect the physical world. Therefore the behaviour of the physical world cannot be fully understood by physical science. If we imagine a world of mere matter, there would be no room for falsehood in such a world, and although it would contain what may be called ‘facts’, it would not contain any truths, in the sense in which truths are things of the same kind as falsehoods. In fact, truth and falsehood are properties of beliefs and statements: hence a world of mere matter, since it would contain no beliefs or statements, would also contain no truth or falsehood. (Bertrand Russell, The Problems of Philosophy, page 70.) Arguments for and against belief in God - Introduction 1. These are not the same as arguments for or against the Bible being true. However if we did have evidence for the truth of the Bible that would be an argument for the existence of God. They are not the same as arguments for or against the Church (or any religion) having behaved well and set a good example. Arguments for and against belief in God - Introduction 2 • Do we need an argument? – Augustine:396-430ad(Bishop of Hippo): • "Thou hast created us for Thyself and our hearts are restless until they find their rest in Thee." – Charles and Di: Charles: In spite of all the advances of science, there lies deep in our soul an anxiety that something is missing - an ingredient that makes life worth living. Di: There is an overwhelming sense of loss and isolation that undermines people's lives. They know something is missing. Arguments for and against belief in God - Introduction 3 • Do we need an argument? - continued. • Calvin: (16th century theologian and founder of the `Reformed branches of Christianity) (QM page 225) – "There is within the human mind, and indeed by natural instinct, an awareness of divinity. … God himself has implanted in all men a certain understanding of his divine majesty …. Men one and all perceive that there is a God and that he is their maker." Can there be arguments against the existence of God? • Consider these two Statements: • 1. There is a spider in here. 2. There is no spider here. – Two different types of claim: • The second implicitly claims that the whole room has been searched. The first doesn’t make that claim. • The statement `God does not exist’ claims that all reality has been investigated - which would seem impossible. • Some believers in God do claim that whole of nature declares the the existence and glory of God. (Psalm 19) – Some say the existence of evil shows there is no God. (We consider this later in the module.) – There are arguments against the arguments for the existence of God. Interlude: The Big Bang • Not the theory that there was an explosion of hydrogen gas! – There was no hydrogen gas; no laws of physics (as presently understood); no space-time. – It is thought these came from the Big-Bang. – It seemed like an explosion out of nothing! – Therefore many saw the Big Bang theory as a confirmation of the Biblical statement that the universe had a beginning and is not eternal. • Gen 1:1 `In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.’ – However it isn’t as simple as that. • This is covered in more detail in my module: Philosophy of Science and Religion. The mystery of existence. • Why do matter and energy exist? - where did they come from? • Scientific theories about the origin of the universe have to assume the initial existence of some kind of energy/law of nature. (Eg: Wave function of the Universe - Stephen Hawking’s phrase) – leading to matter/space-time/laws of physics in the big bang. • But scientific theories cannot explain how the initial energy/laws of nature came to exist or why they exist or did exist. • If God exists why does He exist? Was He created? • Whether or not God exists we are face to face with the mystery:Why does anything exist at all? – Stephen Hawking:`Why does the universe go to all the bother of existing?’ – JJC Smart (atheist philosopher): Why should anything exist at all? - it is for me a matter of the deepest awe. – See Handout re Quentin Smith (atheist philosopher)’s comments. The Mystery of existence - cont. Some believe the questions: 'What is life?' 'What is consciousness?’ and related to it: ‘What is my self that only I experience and know? also give rise to fundamental mysteries. Fundamental Mysteries - cont. If science could, one day, fully examine my brain, would the scientist know what I am thinking about? If not, then my mind must be more than my physical brain. My mind affects my behaviour - therefore it is real. So we have something that it real but is not subject to scientific investigation. The Mystery of Existence - cont.. Most believe that: ‘goodness’, ‘morality’, ‘beauty’ and our sense of ‘ought’ are not just the result of our subjective feelings but are objective realities. Goodness, morality, beauty: do have a real effect on the physical world - they effect our behaviour. (They therefore are real.) But they are not open to scientific investigation - (science examines the physical universe), Many conclude that there must be more to reality than the mere physical existence that science examines. World Views: • 1. Atheistic Materialism: – There is nothing spiritual - no god, spirit or human soul. – Impersonal matter/energy/physical laws (in one form or another) are the basis of all that exist - the whole story. • They are eternal • They have developed into the universe including all its life and human life and personal human minds. – In principle the human person, including his/her appreciation of beauty, right and wrong, could, in the future, be understood entirely by physics. • A complete understanding of the human person could, in future, come from a study of impersonal physical laws/matter/energy which make up his physical body/brain and environment. See quotation from Francis Crick on next slide. World Views: Atheistic Materialism continued. Francis Crick: “You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more that the behaviour of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.” (The Astonishing Hypothesis page 3) World Views: 2. Deism: God is entirely transcendent - out there, not in here. – God created the universe with its physical laws and now leaves it to run its course. – There is no continuing relation between God and the physical universe. – God is not relevant to our physical lives. 3. Pantheism `God’ is immanent - in here, not out there. – There is no Creator God distinct from the universe. – `God’ is the spiritual dimension of the physical universe. – God is impersonal. • We tune into God rather than pray to Him personally. • We may pray to spirits but not to God. – All things are sacred in their own right. – The physical/spiritual universe is eternal. World Views: 4. Theism - God is both transcendent and immanent – He is distinct from the physical world but He is with and `in’ all things. – He alone is eternal. – He created matter/energy/laws of physics. – He holds all things in being. – He is personal Mind. – Some believe that we may know Him personally. World Views: 5. Christian Theism. As well as the theism already outlined: • God is love. • He does not remain distant from our sin and suffering. • He stoops to the human level, and bears sin, pain and human death for us. (The Cross) • He lifts us up back to where we belong, forgiving us all our sin. (The Resurrection) • Although this is seen in Jesus, it is a process that occurs throughout history - that is what the Bible is about. • Judgement, new Creation and eternal life are realities. • There our true destiny is fulfilled. Cosmological Argument. A simple form of the argument: The Universe cannot just have popped into existence from nowhere. Therefore there must be a God who created it. Another simple form: – Which is the most likely cause of a finite universe? • Nothing acting on nothing -> finite universe. • Infinite God acting on nothing -> finite universe. – Romans 1:20: For since the creation of the world God's invisible qualities-- his eternal power and divine nature-- have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that men are without excuse. (NIV) Cosmological Argument - cont. – Another form of same argument: • • • • There is a universe. It could not cause itself. It could not come from nothing. It could not be an effect of an infinite series of causes. • Therefore it must be caused by something that is uncaused and everlasting. • Therefore God exists. – Yet another form: • The universe is contingent and therefore it depends ultimately on something that is uncaused. Cosmological Argument - cont. • Does this argument depend on the universe having a beginning? – Thomas Aquinas (13th Century - born in Naples) • believed that this argument would be valid even for an infinite universe. • God the cause for all events: God Time line --------------------------------------------------------- – However Thomas believed the case would be even more convincing if the universe had a beginning. Cosmological Argument - cont. • The Kalam Cosmological Argument: – The Universe must have had a beginning and therefore must have had a cause. – God ------time line -----------------------– (Kalam was a word used for a kind of Islamic philosophy and means `speech’ in Arabic) Some have argued that the universe must have had a beginning otherwise we are left with the belief that there would be an infinite time before anything would happen and therefore nothing would happen! Cosmological Argument - cont. • In response to the Cosmological Argument some say: – the Universe is just brute fact and its existence is ultimately unintelligible. – There is no explanation for its existence - it just exists. – It is not worth asking why it exists. – It just does. • Before we look at other arguments against it, we consider the other main argument for the existence of God that starts with our experience of the universe. Teleological or Design Argument. • Unlike the Cosmological Argument this is not based on the mere existence of the universe but the properties of the universe. • The universe not only exists but seems very well designed. • It seems at least as if it must have a purpose. (the meaning of teleology). • Does not this mean it had/has a purposeful Designer? Teleological/Design Argument (Cont) • Paley's Watch. – Willaim Paley said: • If we find a watch with all its parts fitted together we will not assume that it was brought into being by the blind forces of nature but by an intelligent designer. • The eye is extremely complex therefore it was made by an intelligent designer - God. – Darwin’s theory of evolution weakened Paley’s argument: • It claimed to explain how natural processes alone gradually transform the simple to the complex by random mutation through the sieve of `natural selection’ or `survival of fittest’. • However many now doubt whether living things can be reduced to a combination of simple things. They say that all living things are irreducibly complex. They side with Paley. – The argument continues - eg Dawkins and Behe. Teleological/Design Argument (Cont) • The environment suits us not because of a Designer but because we gradually adapted to the environment. • However some argue that in order for any life to exist the earth and the whole universe must be very special. • Some say the design argument still does have force because the whole universe is ordered. We have reliable laws of nature : – These laws of nature are very finely tuned: • If any of them were different by a very tiny fraction, no stars (such as our sun) nor any solid object could exist. • Some reply that there may be many other universes and so we should not be surprised that one exists where the balance is right. • This ‘Many Universes’ hypothesis is not a response to the Cosmological Argument but only Design argument. • At present it is not science but speculation. Bertrand Russell (famous 20th C British agnostic/atheist mathematician/philosopher greatly respected the argument from design especially as expounded by Leibniz. (He regarded Leibniz, in whom he specialised, as "one of the supreme intellects of all time") BR writes: "This argument contends that, on a survey of the known world, we find things which cannot plausibly be explained as the product of blind natural forces, but are much more reasonably to be regarded as evidences of a beneficent purpose.” He regards this familiar argument as having “no formal logical defect". He rightly points out that it does not prove the infinite or good God of normal religious belief but nevertheless says, that “if valid,” (and BR does not give any argument against it) “it demonstrates that God is vastly wiser and more powerful than we are". (See his chapter on Leibniz in his History of Western Philosophy). More arguments against Cosmological and Design arguments. What caused God? There must be something without a cause. Why not say the universe is this thing? Just because individual things in the universe need an explanation that does not mean that the universe as a whole needs explanation. David Hume (1711-1776) against the Cosmological and Design Arguments. • God's supposed causing of the universe to exist cannot find an analogy of causes in nature because we have no experience of things beyond nature and the alleged creation would be so unique an event that there is nothing to compare it with. This means we cannot speak of causation or design from the things of our experience and apply them to the origin of the universe. • However some believe that in his famous book: `Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion’, Hume was really arguing with himself. • In the book Cleanthes supports the Design argument and Philo is against it. • Whose side was Hume really on? Was he unsure? More arguments against Cosmological and Design arguments Would we not perceive the universe to be ordered even if it wasn't? Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) believed that human minds impose their own order on the universe. We cannot get beyond our minds and know that nature really is ordered or that effects really must have causes. (Very few scientists take this Kantian view of their work.) He therefore rejected the Design and Cosmological arguments for the existence of God. However he did believe in God but for another reason. - the reason commonly called the `moral argument’. The argument from religious experience. – Non rational argument (not irrational) – Based on experience of `the other' `the holy'. – Rudolf Otto (1869-1937) and the sense of the `Numinous’. • Three aspects of the sense of the numinous: –Wholly Other –Dread in the presence of the Holy. –Mercy, Grace, love. Religious experience includes such specific experiences as: the deep questionings that come from the wonder of the greatness (and infinity?) of the cosmos sense of awe & mystery in the presence of the holy feelings of dependence on a Divine power the sense of guilt and anxiety accompanying belief in a divine righteousness and/or judgement the feeling of peace that follows faith in Divine forgiveness. Near Death experiences - considered a few slides on. • Is religious experience evidence for the existence of God? –It is for the one who has the experience. –See William Rees Mogg’s Times article (2.9.2000) and following letters. The argument from religious experience (cont) Some reject the religious experience argument saying: The religious experience is private and therefore cannot be verified. Religious experience and belief are caused by physical effects in the brain: (Medical Materialism). If that were true then all beliefs (including atheist beliefs) would be invalidated. The argument from religious experience (cont) Susan Greenfield’s studies on the brain show where religious feelings are located and how they can be induced. But feelings of pain - in the arm (say) - also can be artificially induced. Does that invalidate external influences on the arm as the cause of pain? Of course not! Pains in the arm typically are caused by the arm being hit or knocked by something. The brain state of `pain in the arm’ is not normally the whole story. Are religious brain states the whole story? - that is the question. The argument from religious experience (cont). • A significant number of people who recovered from the gates of death - heart, breathing and brain activity having stopped - claim to have looked down on their ‘dead’ body and then travelled to another world before returning to their earthly body. • Such a ‘Near Death Experience’ (NDE) could be shown to be valid if the person experiencing it were able to learn something about the state of the hospital room (say) that he/she could not have known from the position of the body. – This has been claimed many times especially in medical research done in the Cardiac departments of some Dutch hospitals. – An impressive report of scientific findings was given at the 2003 Edinburgh Science Festival. Participants and speakers at the ‘Out of Body’ ‘Near Death Experience’ (NDE) lecture: • David Lorimer, Scientific and Medical Network; • Dr Olaf Blanke, Dept. of Neurosurgery, University Hospitals of Geneva and Lausanne; • Dr Pim van Lommel, Consultant Cardiologist, Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem, Netherlands; • Dr Peter Fenwick, Institute of Psychiatry, University of London; • Professor Bob Morris, Koestler Chair of Parapsychology, University of Edinburgh. For more on the scientific research see: ‘The Lancet’ December 15th 2001. Pre-talk publicity said: “Surveys show that ‘out-of-body’ experiences (OBEs) are not uncommon: between 10% and 15% of populations across the world have experienced an OBE. [These experiences may or may not be associated with a near-death experience (NDE).] Approaches to the OBE centre round the question: does the self or consciousness actually leave the body? Some recent scientific research in Switzerland indicates that the feeling of leaving the body can be stimulated experimentally. The researchers propose that the OBE is simply a distortion of the bodily image arising from stimulation of the reticular activating system (RAS). So are spontaneous OBEs also illusions due to temporal lobe activity? Possibly not. Experiments by Professor Charles Tart in the 1970s showed some success in out-of-body experiences correctly reporting five digit random numbers. And confirmed reports from near-death experiencers suggest that they can accurately recount events that occurred while they were unconscious and clinically dead. Some OBEs are even reported by patients whose hearts have stopped. And since it takes just over 10 seconds before all electrical activity in the brain ceases after the heart has stopped, these reports point to the possibility that our consciousness may not be entirely dependent on the brain. If this proves to be the case, then much of neuroscience, psychology and philosophy will need to be radically rethought.” Interesting results of research reported at the April 2003 Edinburgh Science Festival. NDEs are reported by 18% of resuscitated patients often involving: • Seeing the old body from above. • Watching medical procedures • Seeing beyond the hospital even to distant places where the mind focussed. – Such knowledge gained was later verified. • A review of earlier life including childhood. • Travelling down a tunnel to a beautiful light where deceased family members and a religious figure are there to welcome. • An awesome experience of peace, unconditional love, beauty and freedom. Not all experience all of these phases. Many return to their body after the first one or two stages. • Attempts have been made to explain these experiences from the consequences of the body closing down and starving the brain of oxygen. It is alleged that this lack of oxygen would produce illusions including an illusion of light. • However those addressing the Science Festival said this could not provide an explanation because: – The experiences happened when the brain had become completely inactive. – The reported sensory experiences (visible, audible and tangible) were clear and coherent and could not come from a failing brain. – People born blind who had never seen anything report seeing clearly as the experience progresses. In answer to questions afterwards we were told: Previous culture or religious practice are not relevant to the experience/non-experience of NDE. • The religious content experienced does not always correspond with the person’s previous religious beliefs. • There was no statistical difference between reports from religious former West Germany or from nonreligious former East Germany. – Type of illness/accident, or drugs used in treatment, are not relevant to the experience/non-experience of NDE. – NDEs usually (but not always) lead to: belief in the after life; transformed attitudes to other people; a belief in purpose for life on earth; a loss of fear of death. In answer to my question (asked after the meeting) I was told: Typically the person feels that his/her new life is embodied & clothed. • The clothes are not those worn in the hospital bed, but clothes associated with his/her life when he/she was in the prime of life. Near death experiences almost always convince those who experience them that God exists. There are some known exceptions e.g.: • A.J.Ayer, during his middle years was one of the most famous 20th century atheist philosophers. – But late in life, he had a `near death’ experience. • (It was actually an unpleasant version of an NDE) – In his article `What I saw when I was dead’, he wrote:: "The only memory that I have of an experience, closely encompassing my death, is very vivid. I was confronted by a red light, exceedingly bright, and also very painful even when I turned away from it. I was aware that this light was responsible for the government of the universe .." • What kind of response and evaluation of his experience did A. J. Ayer make? "My recent experiences have slightly weakened my conviction that my genuine death, which is due fairly soon, will be the end of me, though I continue to hope that it will be. They have not weakened my conviction that there is no god." How do we make Moral Decisions? Deontological Ethics. Based on Principles. Two opposite principles about abortion. • Roman Catholic View: Killing an unborn foetus is always wrong. • Radical Feminist: Abortion is right because a woman should always have the right to control her own body. Some have the principle: Freedom of Speech should have first priority. But another person has the principle: Propagation of Evil should not be allowed. Problems with Deontological Ethics. • There are contradictory principles. – How do decide between two principles? – From where do we get our principles? • From nature? – That assumes that what is in nature is good. – How do we define nature? • People’s understanding of nature keeps changing. – We should follow our conscience. • However different people’s consciences tell them to do different things. Consequential Ethics. (Teleological Ethics.) We define what is good by what will have a good outcome. Problems with Consequential Ethics. We do not know the outcome. The consequences of our own action is unpredictable. The consequences of other people’s actions which impact on our actions are also unpredictable. We do not know what the consequences will be of our action in the long term. Nor can we control the consequences. Greatest happiness of the greatest number. (Utilitarianism) • Add up the happiness in one person and then multiply the total happiness in the total number of people and subtract the total pain. – If the result is positive then the action is good. – If the result is negative then the action is bad. • Problems: – How do you measure ‘pleasure’ or ‘pain’? – Pain and Pleasure are not exact opposites. – How do you protect minorities against the will of the majority? Relativism. • Everything is relative. Nothing is absolute. – Is this a relative or absolute statement? • Relativists do emphasise the principle of tolerance. – Therefore relativists do have at least two absolute principles. (i.e. ‘Everything is relative’ and ‘We must be tolerant’.) • Should we tolerate intolerance? In practice most people use a combination of each of these principles. • Deontological Ethics – based on principles. • Consequential Ethics – based on consequences. • Utilitarian Ethics – based on the ‘greatest happiness of the greatest number’. • Someone who exhibits true goodness we say is a virtuous person. • But virtue cannot be measured, exactly defined, or quantified. Christian Ethics. • Not based on measurable principles but on the Person of God. • We cannot exactly define ‘personality’. However we do know when we meet a genuinely good person. (A person with virtue.) • Christian goodness and morality is based on the goodness of the Person of God shown in the Person of Christ. The Objective Validity of Morality and Goodness. – Objectivist Ethics: • There is something called goodness which is independent of us - out there in the world or revealed by God. –This action is good - means it conforms to that goodness. –This action is bad - means it is in opposition to that goodness. • Subjectivist Ethics. – There is no goodness independent of us. – Our idea of goodness comes from: • Our biology. • The results of evolution. – Each individual person OR each individual society is the criterion for deciding the difference between good and evil. . A major problem for Subjectivist Ethics: – How do you settle a dispute about what is good? – There is nothing to appeal to. • In 1960, Bertrand Russell wrote: • 'I cannot see how to refute arguments for the subjectivity of moral values, but I find myself incapable of believing that all that is wrong with wanton cruelty is that I don't like it.' (Notes on Philosophy, January 1960, Philosophy, 35, 146-147.) This problem is more graphically illustrated in the hypothetical example given in the next slide. Hitler believed that only some human life is valuable. He ordered the killing of millions of people, believing humans of their race have no value at all. – He felt like it, believed it to be right, and so did many others. – Suppose he had won the war, brainwashed or killed those who disagreed with him, – so that the remaining human society came to believe that the genocide was right, • would that have made it right? Or is there some objective goodness - independent of a person or society’s beliefs and feelings - that says it is wrong even if every person believes it to be right? Are certain actions intrinsically right or wrong or are right and wrong merely matters of public opinion? C. S. Lewis’s ‘Mere Christianity’ and the ‘Moral Argument’ - this book was the turning point, from atheism to Christianity, in Francis Collins’ life. (He was the head of the Human Genome project and wrote the book: ‘The Language of God.’ [DNA is a form of language or code.] • We have heard people quarrelling. • They say things like this: How'd you like it if ….? That's my seat I was in it first. Give me a bit of your chocolate, I gave you some of mine. Come on you promised. • The person who says these things is not just saying that he doesn't like the behaviour - rather he is appealing to a higher standard which he expects the other person to know about. • The other person seldom replies: `I don't believe in fairness, or kindness or keeping promises.' `I don't believe in standards of behaviour'. He will try to say that there is some special reason why he did what he did. There is another reason why he should have taken the seat, Things were quite different when he was given the chocolate, Something else has turned up to stop him keeping the promise. Quarrelling shows that we try to demonstrate that the other person is in the wrong. He has offended ‘right’ behaviour. • So some say that everyone instinctively recognises there is a difference between right and wrong and does not need to be taught its basic principles such as fairness, honesty, kindness, courage etc. – (They do not mean that there are not some people who are completely oblivious to the difference - after all some people are colour blind and can’t tell green from blue.) Others reply and ask: What about the differences between cultures? However in no culture do people regard kindness as evil, or double crossing people who have been kind to one as good, or cowardice as good. • There have been, and are, moral differences between cultures but the differences are not about whether kindness, fairness, generosity, honesty etc are good or evil, but – how these should be applied and – whether they should be applied to all or just to a privileged group. Two Verses from the Bible which say the same thing: • Romans 2:14-15: • Indeed, when heathens, who do not have the law, (ie The 10 Commandments etc) do by nature things required by the law, they are a law for themselves, even though they do not have the law, since they show that the requirements of the law are written on their hearts, their consciences also bearing witness, and their thoughts now accusing, now even defending them. Where did this moral sense come from? • (1) Either it comes from physical world: (a) Our sense of right and wrong is an instinct that has come from our biological make up or psychology which are the results of random evolutionary processes. (b) Our sense of right and wrong comes from social conventions we have learnt. © A combination of (a) and (b) (2) Or it comes from beyond the physical world: the Spiritual world or God. Even if (1) (ie our sense of right and wrong comes from the physical world) is part of the story, can it be the whole story? Can either of the explanations from the physical world be right? • Consider the first. Our psychology - result of random evolutionary processes - has led us to value kindness and selflessness.. • But if the sense of goodness is just an instinct which is the result of `survival of fittest' then does it have any intrinsic value? Is morality only the instinct to preserve the species? • If we hear of someone in danger there will be two contradictory instincts: – Herd instinct to help him - preserve the species. – Instinct to avoid danger - preserve the species. • We will also feel inside us a third thing which tells us we ought to suppress one instinct and encourage the other. • There are appropriate times for each instinct. • Morality tells us that at this time, such and such an instinct should be encouraged. Therefore morality is not just a physical instinct. Leaving C. S. Lewis’s argument for two slides we note something said by Richard Dawkins (Atheist biologist). In his book: The Selfish Gene, p. 2: "I shall argue that a predominant quality to be expected in a successful gene is ruthless selfishness.... Be warned that if you wish, as I do, to build a society in which individuals cooperate generously and unselfishly towards a common good, you can expect little help from biological nature. Let us try to teach generosity and altruism, because we are born selfish." • Richard Dawkins does not seem to realise that his desire that we be taught to be unselfish against our biology - implies –that there is purpose to human existence –that something has gone wrong with our human being which should be countered by Returning to C. S. Lewis’s argument: • Where does our moral sense come from? – Not as we have seen from our biology. Has it come from social conventions we have learnt? • The problem is that there are differences between social conventions. • Do we ever think that one is better than the other? • Do we think we have progressed - ie improved our social conventions? • If we do then we are implicitly acknowledging another greater Real Morality by which we judge one morality against another. • Suppose two of us had an idea of what New York was like. • Your idea might be truer than mine because there is a real place called New York by which we can compare our ideas. • But if we only meant `the town I am imagining in my head' (there being no real New York), one person's idea would be no more correct than the other person’s idea. • If there were no such thing as Real Morality but just what cultures had made up themselves - there would be no meaning to the statement that Nazi morality is inferior to another morality Universal agreement that fairness, honesty, kindness etc are good and not evil, cannot be a mere world wide social convention because different cultures believed them to be good before they had met one another. A different form of the argument that morality must come from beyond the physical world. Can one derive an `ought' from an `is'? • Science can tell us what is the case, but can it tell us what ought to be the case? – Electrons behave as they do - that is neither morally right nor wrong - it is just the way things are - the whole story. – We behave in certain ways but that is not the whole story for we know we ought to behave in other ways. – Therefore there is more than one kind of reality. – One of these realities is subject to scientific investigation and discovery - the other one isn’t. If our moral sense is not mere biology/ psychology nor social convention then: –it must have come from beyond the physical world. • That is what religion is about. This is the basis of C. S. Lewis’s argument. -------------------------------------------------------------------- My own view: • Rather than saying there must be a ‘Moral Law’ coming from beyond us, I prefer to say: – Beauty, grandeur in the universe and the world are objective realities. • When we say: ‘The valley is beautiful’ we are not merely talking about our own feelings. • We are claiming that beauty is something that is actually there. My own view continued: Beauty and grandeur are connected with goodness which is also something real. Evil and suffering are alien intrusions. Although we may not recognise it at first, the Spirit and Word of God (the source of creation, beauty and goodness) impinge upon us all and therefore we recognise righteousness when we see it and evil when we see it. Read handout: ‘The Gospel according to science’ by physicist Paul Davies and ponder the points below: He believes we must use science to find moral values. • Does he indicate what he means by goodness? • As well as good he believes humans commit much evil. • There is an underlying assumption that the survival and future happiness of our species is the final goal of goodness and morality. – If, as he says, we do evil things, why should our survival be a `good’? Even if it is the case that our survival and happiness are good things, does that belief follow from science? If not science then what? Our desires? Do our desires determine what is ‘good’? What about competing desires? • Paul Davies wonders how science can be used to give us moral values. –Does he give any indication of how this might be possible? –If not, why do you think he fails (and is bound to fail) to find a solution to his problem? • Can we get an `ought’ from an ‘is’? (See six slides back.) Read handout: ‘Michael Ruse and . reductionary illusions.’ by John Byle. • Michael Ruse’s theory is that there is no real ‘good’; it is just a useful illusion that helps preserves our species by making us behave more co-operatively. – (If the ‘good’ is an ‘illusion’ why should it be ‘good’ that we behave co-operatively?) Michael Ruse believes that morality comes from our genes that trick us into thinking that co-operation is objectively ‘good.’ He believes, then, that understanding morality can be reduced to understanding our genes. He has a reductionist view of morality. John Byle argues that this theory refutes itself and therefore cannot be true. A Christian View of the source of our moral sense: Our moral awareness must be something above and beyond what we actually do. Something real that is pressing on us though we often try to forget it. • We, from the inside, know there is a moral imperative. – We cannot follow it. – God comes to us and from the inside makes us what we ought to be. Read and study handout: `Lord Hailsham on the Objective Validity of Morality’. =================== Nietzsche - rejects objective morality. He says: God is Dead’ Thus Spake Zarathustra begins with pronouncement by Zarathustra that God is dead. Because God is Dead (said Nietzsche) : It follows that: · the physical world with its physical laws is all that there is. · Our thoughts are not really thoughts but just the laws of physics controlling our brain. As for the superstitions of the logicians, I shall never tire of underlining a concise little fact which these superstitious people are loath to admit - namely that a thought comes when it wants, not when `I' want; so that it is a falsification of the facts to say: the subject `I' is the condition of the predicate `think’. (Quotation from his `Beyond Good and Evil’) (By ‘superstitions of the logicians’ he means the beliefs of scientists and others who say: “I know such and such…”) Here Nietzsche is saying two related things: 1. There is no real ‘self’ (`I’) that can initiate anything. All actions and ‘thoughts’ are the result of impersonal physical laws. 2. `Thinking’, as we normally consider it, is impossible. ·This has made our normal understanding of truth unintelligible. ·There is no objective purpose to life - no good and evil. ·Therefore morality is an illusion. In MSP3 we consider Nietzsche’s advice on how to cope with the seeming meaninglessness of life. Before we go on, consider an extreme example of Nietzsche’s rejection of objective morality: "Who can attain to anything great if he does not feel in himself the force and will to inflict great pain ? The ability to suffer is a small matter: in that line, weak women and even slaves often maintain masterliness. But not to perish from internal distress and doubt when one inflicts great suffering and hears the cry to it - that is great, that belongs to greatness.” Friedrich Nietzche, 'The Joyful Wisdom', trans. by Thomas Common (New York: Russell and Russell, Inc., 1964), p.25. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- The Problem of Evil • Two kinds of evil: – 1. Moral Evil. • Why do people behave badly? • Is God to blame for creating us with the capacity for evil? • Why does He not stop us doing evil? – 2. Natural evil. • Why are there natural disasters - such as earthquakes etc which surely cannot be blamed on us? The Problem of Evil • For a journalist’s summary of the problem for various religious beliefs see the handout: – `Paul Nathanson finds Michael Buerk grappling with how to reconcile divine goodness with the evils in the world.’ The Problem of Evil • Intellectual problems for all world views. For the theist: • If God is good and powerful why is there evil and suffering? For the pantheist: • If the natural world (which contains evil) is part of God, does not that mean that God Himself is partly evil? • If the natural world is eternal, does not that mean that evil is eternal and there is no salvation? • Does it make sense to say we should try to escape the cycle of re-incarnation when we have already had an infinite time? • In response pantheism often denies the existence of evil: – saying, the way things are is the way `things are meant to be´, – and giving us advice on how to cope with suffering in ourselves and others. Problem of Evil • For more on the problem of evil for Hinduism and Buddhism see handout entitled: Response to the Problem of Evil in the main Pantheistic or Panentheistic Religions – Hinduism and Buddhism • For a comparison of monotheistic and pantheistic responses to suffering see handout taken from the Daily Telegraph and written in response to the Glen Hoddle controversy. (Glen Hoddle had said that disabled people were bearing the consequences of bad behaviour in a previous incarnation.) The Handout’s title (using the Daily Telegraph’s own title) is: – `The true purpose of suffering.´ Problem of Evil (Cont) • For the atheist: – If the atheist challenges the theist saying ´Why does evil exist?, is he not acknowledging the existence of good? – How does he distinguish between good and evil? – If he does distinguish good from evil does not that imply the existence of an objective goodness? • an objective goodness which is independent of our private opinions and biology? – Here is his problem: Atheism cannot allow for an objective goodness which is outside us. – His only option seems to be to deny the existence of real evil. • Only a very few atheists are prepared to go that far. • In MSP2 and 3 we consider some of the atheist beliefs that explicitly deny the objective reality of good and evil. Christian responses to the problem of Suffering and Evil. Evil is a necessary by-product of nature. All things, including evil finally contribute to the goodness of the whole. Eg: Our love and courage are strengthened. God is not indifferent to suffering: In all our affliction He too is afflicted. The Cross focuses God’s suffering with and for us. The resurrection of Christ is God’s final answer to evil, suffering and death. Evil is temporary. Eternity, where justice, love and truth prevail, is a reality. Christian responses to the problem of Suffering and Evil -cont. • For a previous Lord Chancellor’s comment on Innocent Suffering see next slide: – Lord Hailsham’s Comment on Innocent Suffering. .`(The Door Wherein I Went' page 70) What does shock us, is that the innocent suffer so often as the result of the wrongdoing of the guilty. But this is not as paradoxical as it sounds. As the Devil pointed out to the Almighty in the book of Job, if God was always seen to reward the righteous in this world for doing right, it would be seen, and very soon said, that the righteous were only doing right for what they could get out of it. But God does not desire this kind of obedience. He is set on creating beings with a free will, in a world in which they themselves are responsible for the consequences of their own choices and desires the free obedience of intelligent and reasoning creatures. Only when Job begins to suffer unjustly and still will not curse God is it seen that he does not serve God for what he can get out of it. The suffering of Job, like the Crucifixion and Passion of Christ, is seen to be the consequence, not of Job's own guilt, but of the presence of evil in the world, and the need for it to be seen that good must be pursued for its own sake, even occasionally, at personal sacrifice. Christian responses to the problem of Suffering and Evil -cont. • God purpose was to create and redeem human beings so that they would do good for the sake of goodness rather than just for a reward. – So in this world, pain and happiness exist side by side. 1 Pain exists but is defeated in the end. 2 Good people as well as bad´suffer but the good are eternally rewarded in a another world presently unseen.. 3 God shares our suffering & ultimately triumphs over it. 4. Ultimately goodness, love and mercy reach fulfilment in the context of evil and pain. A famous book on this subject is: CS Lewis's `The Problem of Pain´.